The Danube Valley: central Europe’s answer to Silicon Valley

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Peter Thiel, co-founder of PayPal and a prominent Silicon Valley investor, once complained that “we wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters”.

But those who, like Mr Thiel, feel the tech industry lacks the ambition to tackle real problems in the world, should visit Bratislava.

The Slovak capital, whose medieval churches and cobbled streets bear scarce resemblance to the sprawl of San Francisco, is part of a network of cities in this region that hope to become central Europe’s answer to Silicon Valley. They even have a name to fit the vaulting technological ambitions — The Danube Valley.

Slovakia’s economy is still heavily reliant on the car industry, which accounts for almost half its entire industrial output. Volkswagen, Kia, Peugeot and now Jaguar Land Rover all have manufacturing plants in the country.

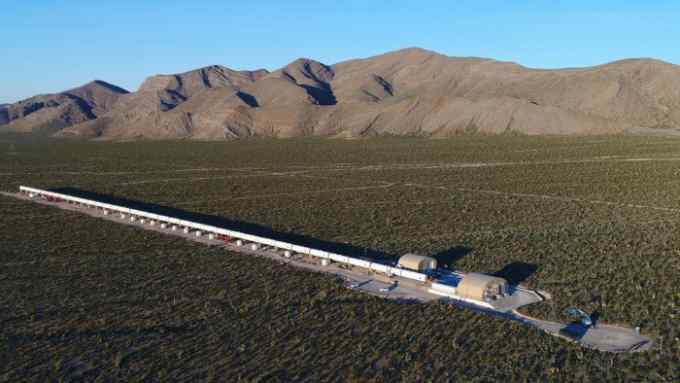

In the past few years, however, new technology start-ups have emerged that are shifting the economy away from a dependence on heavy manufacturing. Juraj Vaculik, chief executive of Aeromobil, the flying carmaker, is an archetype of this transformation. He was a student leader in the early days of the Velvet Revolution in 1989, which freed the former Czechoslovakia from Communist rule, and then made his fortune from running a successful marketing business.

“In 2010, an old school friend Stefan Klein called me with an idea of making a flying car,” he says. The duo then embarked on their attempt to revolutionise personal transportation, competing with Silicon Valley companies such as Kitty Hawk, a start-up backed by Google co-founder Larry Page.

There have been other successes. Eset, a cyber security software developer established in Bratislava in the early 1990s, is today supplier of one of the world’s most widely used antivirus systems. Similarly, Sygic has developed a popular mobile navigation apps used by 200m people worldwide. A Slovak games development studio, Pixel Federation, develops many of the games on the social network Facebook, such as Train Station and Diggy’s Adventure.

Slovak start-ups have benefited from the fact that costs are far lower in the country than for rivals in richer economies. Technically minded graduates are easy to find and the limited size of the local market nudges ambitious entrepreneurs towards seeking out international sales faster.

“The Slovak market is very small, so we had little choice but to look beyond to global markets to scale up,” says Michal Stencl, founder of Sygic. “We were building a global business from the start.”

A younger generation of founders are now following their lead. Photoneo, for example, has built a 3D camera that can recognise objects at high speed allowing a robot to, for example, pick out particular tools or components in a factory. Another start-up, GA Drilling, is rolling out technology that uses electric plasma to help drill more efficiently for oil and gas underground. A string of internet companies, such as Slido, an audience interaction app, have established themselves in internet markets in the UK and US.

“The [innovation] ecosystem has in recent years moved forward and matured,” says Peter Kolesar, chief executive of Neulogy, an innovation consultancy based in Bratislava. “Today there are inspiring stories of successful firms, but also experience from entrepreneurs, investors and mentors to help get new projects off the ground.”

Entrepreneurs still face funding challenges. Slovakia has seen a stream of EU research and innovation funding worth nearly €4bn since it joined the bloc 13 years ago. However, private capital can be tough to find, which can stifle late-stage projects at a crucial stage of growth.

“For the country’s ecosystem to grow, it requires more than start-up funds,” says Simon Sicko, founder of Pixel Federation. “The big challenge is to build institutions that will provide growth capital for scale-ups.”

Though start-ups can benefit from government cash handouts, industrial policy and regulatory burden can also stifle entrepreneurs. Legislation is viewed as favouring larger companies over smaller enterprises, and tax breaks appear to benefit foreign investors promising to bring manufacturing jobs to the country more than smaller innovative ventures.

Another problem is a scarcity of workers with skills and business experience. While many Slovak expats could bring valuable business experience from abroad, the country’s political climate, marked by endless corruption scandals, does little to encourage them to return home.

Some entrepreneurs are turning these very limitations into an opportunity.

Initiatives to fight corruption, digitise public services, set up better schools, and encourage Slovaks abroad to return home have popped up around the country, founded or backed by successful entrepreneurs. Others have joined advisory boards of younger start-ups or become angel investors themselves.

“There is a lot of talent and hunger there,” says one investor from London involved in the local market. For Slovak entrepreneurs, that applies not just to building businesses but also to improving the country.

Additional reporting by Peter Campbell

Comments