‘Would you like a ski room with that?’ On board the new superyachts

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“There isn’t anything on a well-designed yacht that isn’t purposeful,” says Jonathan Quinn Barnett. “Every cupboard, every storage area is full. It’s either got wet rope in it or food for next week.”

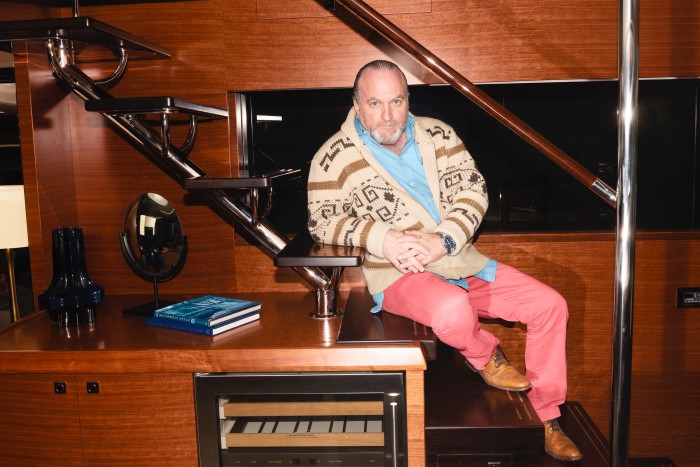

Barnett, a designer based in Seattle, has been drawing and building superyachts since the late 1980s. He is best known for designing the insides of Octopus, finished in 2003 for Paul Allen, a founder of Microsoft. Before that, he worked for Industrial Light and Magic as a model-builder and storyboard artist – he built the scale model of the Golden Gate Bridge for Star Trek IV. “But I wanted to build real spaceships,” he says, “something that you can get in and go somewhere.” Something that generates its own power and carries its own supplies.

Octopus, at 126m, is one of the world’s biggest and best-known superyachts. But when Barnett sits down with a blank sheet of paper, he tells clients that size is the wrong place to start. “The scale of a vessel is entirely based upon its purpose,” he says. A decision on length sits at the very end of what he calls the design spiral – a list of increasingly detailed questions about what the yacht is supposed to do. Every answer is a line on a drafting table. That’s your hull.

Yachts are lovely machines, but they have no real reason to exist. They don’t shoot missiles or carry freight like other boats, so when you buy a yacht, you have to sit yourself down for an interrogation. You are paying for something that will never be anything more than comfortable to sit on and nice to look at. Why would you do that? Answer honestly and you will buy the right boat. But be careful: a yacht is a plan for the future. When you buy one, you are deciding what kind of person you would like to be.

I am the kind of person who likes to poke around on boats that other people have paid for. And so Alex G Clarke, a broker at Denison Yachting who co-founded its superyacht division, has arranged for me to poke around on 7 Diamonds, a big, gorgeous yacht designed for a specific purpose. It is waiting in Fort Lauderdale for repairs and cleaning. Crew and day labourers are already on board, and a pile of flip-flops has been discarded at the bottom of the gangway. I add my shoes to the pile and am mortified to realise that I have also become the kind of person who wears socks.

At 32m, 7 Diamonds is on the small end of what we could call a superyacht. There are fewer than 6,000 privately owned boats this length or longer in the world; a third of them were built in the past 10 years. 7 Diamonds comes out of Numarine, a yard in Istanbul that makes large, semi-custom boats – they’ve got a few basic hull shapes, and they’ll fit them out however you like. The first owner of this yacht took delivery in December and liked it so much he has already gone back to Numarine for a bigger one. A little over six months old, 7 Diamonds is already on its second owner. Alex, who has just closed the sale at $10.75m after a bidding war at the Palm Beach Boat Show, assures me that this is how the industry works.

I had heard that if you buy a superyacht, you need to expect to pay 10 per cent of the boat’s value in running costs every year. I ask Clarke whether this is true, and he squints and cocks his head. “Well,” he says, “More. Could be 12 per cent,” he says. A yacht, particularly one this size, is a small company that manufactures joy and loses money.

A lot of people bought big boats last year. Yachts are inherently suited to a pandemic: you put your family on board, you pull in the lines and then you disappear. The 2020 numbers are a little deceptive, since both sales and construction collapsed during the uncertainty of March and April. But by May, kids were getting out of school, summer plans had been cancelled and everyone in the yacht industry began having the busiest year they’d ever known.

Even with only half a year to work with, brokers sold 414 superyachts in 2020, according to data from Boat International, an industry magazine – that’s more than in the entire year of 2019. Sales were already at half that number in the first quarter of 2021 alone. People who wanted five-year-old boats are settling for 10-year-old boats. Boats that had spent two years on the market in the past are now gone in a month.

New-builds tell an even more dramatic story. Yards are on pace to deliver 494 new superyachts this year, up from 341 in 2020. The biggest of these boats, the leviathans over 100m, can only be built in a few yards, most of them with experience in “grey boats” – naval vessels. Feadship pulls it off, with four yards in The Netherlands; or Lürssen, with nine yards in Bremen, Hamburg and northern Germany; or Fincantieri, in La Spezia in Italy. But boats that big don’t come down the ways very often.

If you’re going to buy a boat, your first and most basic question is this: do you want to go a long distance with a lot of stuff, or a short distance very fast? As a boat floats, it displaces the water. The higher the displacement, the more a boat can carry. Some boats, however, will get on a plane as they speed up – a boat on a plane is surfing down a wave created by its own bow. Planing is fast, because it lowers displacement and drag, but it’s hungry for fuel and horsepower.

Barnett points out that from the waterline down, the motor yachts of the early 20th century looked a lot like sailboats. The USS Potomac, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidential yacht, was long, narrow and efficient, with a fine entry and exit – it was pointy at the front and the back. After the second world war, however, yacht designers had better, more powerful engines. “You can get much less fine and much less efficient if you have massive amounts of horsepower to throw at the problem,” says Barnett. And designers realised that they had enough power to get a large private yacht up on a plane, just like the fast PT boats the US had used in the Pacific.

Most superyachts are still dealing with this basic trade-off: efficient and huge, or inefficient and fast? Build a leviathan, and you get to decide that you can just be huge and fast. The world’s longest yacht remains Azzam, owned by the president of the UAE, which Lürssen launched in 2013. It stretches 180m overall, a nose longer than a US Navy Ticonderoga-class cruiser (a ship that size can cost more than $500,000 to fill). Azzam can hit 33 knots in shallow water – the same top speed as that cruiser. To understand what that means, first imagine Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, home of the Duke of Marlborough. Now: imagine Blenheim Palace cornering at speed on a Formula 1 circuit. That is, in the biblical sense of the word, awesome. It cheats the laws of matter.

Lürssen does most of its business between 60m and 90m, according to Michael Breman, the company’s head of sales. A yacht of that size starts at €180m, according to Boat International, but there are also practical limits to size. At 80m, you need to hire a local pilot to guide the boat in the south of France. At about 90m, maritime law requires the crew to have different certifications. If there are more than 36 people aboard, your yacht becomes a commercial vessel.

Lürssen has got good at installing banjas (Russian-style extended spas). They’re putting full open-air galleys – kitchens – on open decks. They’re building ski rooms, so guests can kit up before climbing into the helicopter. Median length on deliveries has increased over the past 25 years, from the high 50m to the high 60m. But the company is also re-learning how to build small – or, rather, “small”. Lürssen launched a 56m yacht last year, its first in 15 years.

I am not jealous of whoever it is who scoots around without compromise at 30 knots in Blenheim Palace. Honestly – I’m not. I do have a list of boats I would like to buy. I grew up working on boats, building them, repairing them, crewing them. It is my firm conviction that what money you have should be spent raising children and floating around with them on the water. But what has always appealed to me about boats is their limitations. They force you to make decisions: you can’t bring all your stuff on board, and no boat can do everything. Boats are beautiful not despite their compromises, but because of them.

Ruud Bakker, who has been designing yachts at Feadship for over 30 years, says owners are younger now – below 40 or even 30. They want to leave the Med and go to northern Europe or the Antarctic. They want to use less fuel. And the boats themselves are starting to look different. Owners now “want to make more of a statement when the yacht comes into a harbour”, says Bakker. “Not being a wedding cake, but a sculpture.”

That’s the most offensive thing a designer can say about someone else’s yacht – that it’s a wedding cake, a thoughtless stack of decks. If a yacht is a plan for the person you want to be, on a wedding cake you want to be someone with an entourage: you want to float the biggest possible party from A to B. Just like Barnett, though, when clients ask about size, Bakker encourages them to think instead about purpose. How far away is B? How quickly do you want to get there? Is B a proper harbour or a gunk hole – a hidden inlet that’s hard to get to and all your own?

He points me to Sherpa, a 74m yacht built by Feadship that was launched in 2018 and is estimated to have cost in excess of $120m. A client wanted to show his family the whole world, so Sherpa looks like a research vessel. It has a high, plumb bow – straight up and down, like a blade – and flat stern section in the back. It’s topped with a broad, square bridge, with sightlines of the whole ocean, like an aircraft carrier. Sherpa is not faired – nothing has been applied to the hull to cover the welds where steel plates meet to keep the water out. This will make repairs easier, but it also looks super-cool. There has been no attempt to hide the exhaust stacks; their prominence is a statement. “A yacht is not cool by its features,” says Bakker. “It’s good and cool when it serves the purposes of the owner.”

Sherpa is what the industry calls an expedition yacht, or an explorer. Between 2016 and 2020, yards delivered 10 to 20 explorers a year. In 2021, yards have either scheduled or launched 30 explorers, with 27 already planned for 2022. Nicholas Robinson, business editor at Boat International, says the industry might be seeing a shift in what people consider luxury: distance and self-sufficiency are the new nice-to-haves. Owners are deciding they would like to be the kinds of people who would take a few friends across an ocean at 15 knots.

That is exactly the purpose of 7 Diamonds, parked at a dock in Fort Lauderdale. For its length, it’s a beast, with the displacement of a 50m yacht. It’s beamy – it’s wide. It draws a lot, with a hull that drops 2m below the waterline. The bow has a knuckle, with soft lines on either side of the pointy bit that add even more room in the front. 7 Diamonds can carry a lot of stuff, with comfort.

Slip down a narrow metal staircase – a fiddley – into the engine room and you can see the business end of exploration. Zack Rasmussen, the chief engineer, emerges from the bilge, where he has been crouched, barefoot, working on wastewater lines. I ask him what makes an explorer yacht and he ticks off a list: extra generators and fuel storage; better fuel efficiency; a steel hull, “which is major”. 7 Diamonds can generate 280 litres of fresh water an hour. Feeding the twin 800-horsepower Man engines is an Alfa Laval centrifuge running at 20,000 revolutions a minute to purify the questionable diesel you might take on at a questionable port. The rudder has three back-up systems, and in a worst-case scenario the boat can be steered by hand from the engine room with the aid of hydraulics and a walkie-talkie to the skipper.

Can Yalman drew Numarine’s expedition yachts. He graduated from the Parsons School of Design in New York, then worked as an industrial designer before turning to boats. About five years ago, he says, he noticed in conversations that clients were turning away from performance boats, the ones that get up on a plane. New owners wanted “something more robust, something more muscular”, he says. “Something more like an SUV.”

When Zach shows me the diesel centrifuge in the engine room, it is as if we are staring at a Land Rover, admiring the snorkel on the air intake, contemplating the possibility that we might one day drive across a floodplain. I don’t know whether the centrifuge is necessary for 7 Diamonds’ next cruise, planned for the Turks and Caicos. But the centrifuge is seriously cool.

Octopus, Paul Allen’s old yacht, can float a support tender and a small submarine straight out of its stern. It can land two helicopters on a deck that leaves enough space for half-court basketball, then tuck both choppers into a garage on its stern. Barnett found room for a recording studio and a movie theatre.

Right now, though, he’s just finished designing a boat with limitations. What if you know exactly what you want, and what you want is just to see all of the San Juan islands, just north of Seattle, in a couple of days? What if you want to drive the boat yourself? Expedition boats look nice, he says, but they’re slow. So he designed the Horizon V68. At just under 22m, it’s possible to imagine the owner at the wheel. You don’t have to drop down a fiddley to get to the engine room – you can just stride through a watertight door with full headroom. You can see the stern from the bridge, which means you don’t need a crew member with a walkie-talkie to tell you where the dock is.

The V68 also hops up on a plane and tops out at 25 knots. Barnett designed the boat, he says, to be realistic. It answers a simple question: what are we going to do this weekend? He asks me whether I’ve ever made a passage – a long trip over salt water. This is a slightly confrontational question, a bit like asking a gearhead if he can drive a car with a manual transmission. I have, I tell him, and then he pounces. “They’re really boring!”

They can be. I was once trapped on a four-hour night watch on a sailboat pounding into the wind with a man I didn’t know that well who got angry because I didn’t know any golf jokes. I did not enjoy that passage. “If you’re going to go exploring,” says Barnett, “you have to define what kind of exploring you’re going to do.”

He got me.

So you want to buy a boat. Let’s assume that you are not so wealthy that you can buy your way out of a compromise by, say, commissioning an oil-rig tender as a chase boat to hold extra fuel and all your toys. Now: do you want to stay close to shore, get up on a plane and go somewhere fast? Or do you want to be self-reliant and go a long distance slowly? There are no wrong answers. But be honest with yourself. What kind of a person do you plan to be?

Sails of the centuries

North Star

Launched in 1853 and built to carry Cornelius Vanderbilt and 50 guests and crew on a grand tour of Europe. At 270ft, North Star had the lines of a sailboat, with beam engines driving paddlewheels that Vanderbilt was eager to prove would work on an ocean passage.

USS Potomac

Built to be a US Coast Guard cutter in 1934, recommissioned two years later by the US Navy to serve as Franklin D Roosevelt’s presidential yacht. Long and thin, with a sharp, plumb bow. Eventually owned by Elvis Presley (left), drug runners and the US National Park Service.

Nabila

Commissioned from the Italian yard Benetti in 1978 by Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi. At 86m, with a flared bow and a bulb to increase efficiency, it was designed by Jon Bannenberg to be the world’s most luxurious yacht. Featured in the Bond film Never Say Never Again and a Queen song. In the ’80s, belonged to Donald Trump (below, with Ivana Trump, in 1988), who renamed it Trump Princess.

Octopus

Owned by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, Octopus was one of the first and largest examples of an explorer yacht, launched by Lürssen in Bremen in 2003, with a hull by Espen Oino and interior by Jonathan Quinn Barnett. At 126m, it can land two helicopters and store them in a hangar, and launch manned and unmanned submersibles.

Azzam

Owned by the president of the United Arab Emirates, at 180m Azzam is the longest private superyacht in the world. Launched by Lürssen in 2013, it can hit 33 knots, making it one of the world’s fastest too. Designed and engineered by Mubarak Saad al Ahbabi, with an Empire interior by Christophe Leoni – the main salon’s chandelier was designed not to tinkle when the boat is sailing – it is said to have cost more than $500m.

nord

Built in Bremen by Lürssen and launched in 2020, Nord is estimated to have cost $500m and belongs to Russian billionaire Alexei Mordashov. Dan Lenard, co-founder of the Italian studio that designed it, has described it as “a warship wearing a tuxedo”. It has a large pool, two helipads and a fleet of tenders.

7 Diamonds

At 32.5m and launched in 2020, this perfectly illustrates the trend towards “smaller” expedition superyachts. It was built in a yard in Istanbul and is currently docked in Fort Lauderdale, where it was recently sold for $11m. It sleeps 12 and has a Jacuzzi and a VIP site with private deck.

Somnium

Launched this year, this is another more “bijou” superyacht at 55m. Built by Feadship and designed by Studio De Voogt, it has a cruising range of 4,500 nautical miles, sleeps 10 and was commissioned by its owner so they could take three generations of the family on world cruises. On the sun deck is a “Jacuzzi island”.

Data visualisation by Chris Campbell

Comments