Passive investment blamed for inflating stock market bubble

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The trillions of dollars that have flooded into passive funds in recent years have inflated valuations, radically reshaping the US stock market and insulating it from the threat of a sustained bear market, research has claimed.

Vincent Deluard, global macro strategist at brokerage StoneX, argued that the unprecedented flows have led to structurally higher stock valuations disconnected from company fundamentals, benefited large and growth stocks at the expense of value and small-cap shares and resulted in fewer, and shorter lived, market corrections.

“A preponderance of evidence suggests that the rise of passive has played a major role in the stock market bubble of the past decade,” Deluard said. “If the rise of passive is the main cause for this bull market, a sustained bear market can only occur if the passive sector shrinks.”

As of the end of July, $7.3tn was held in passive open-ended and exchange traded funds that invest primarily in US equities, according to Morningstar, outweighing the $6.6tn in comparable actively managed funds, although passive’s overall share is lower when direct investment outside funds is taken into account. Index-based investment has also grown rapidly in some European countries.

Deluard argued this shift from “price-sensitive” active investors to “value-agnostic” passive ones has played a part in pushing up stock valuations.

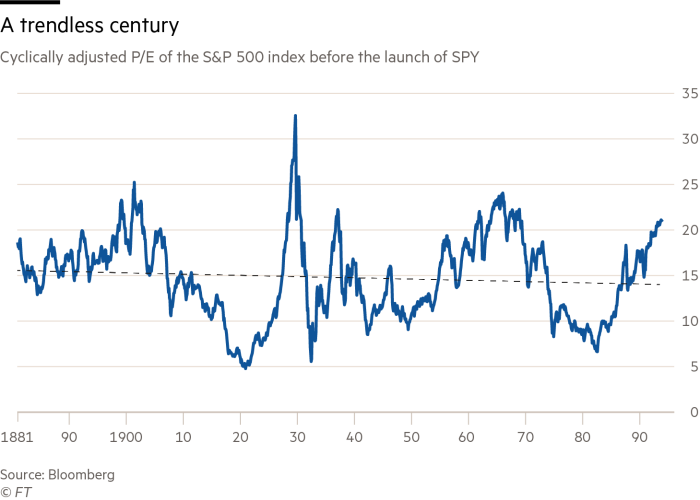

His data show the cyclically adjusted Shiller price/earnings ratio of the S&P 500 index “had no discernible trend” between 1881 and 1993, when the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY), the first US ETF, was launched, averaging 15.4 over this period.

The Shiller p/e measure has risen sharply since 2003, however, and now sits at a record high 38 times.

Deluard does not attribute all this rise to the growth of passive funds. The collapse in interest rates and colossal central bank asset purchases witnessed since the global financial crisis “probably played a bigger role” in increasing stock multiples, he said.

Nevertheless, Deluard estimated that the rise of value-agnostic passive funds accounted for 27 per cent of the increase in the cyclically adjusted Shiller ratio.

He believed this pattern held internationally as well, with there appearing to be a positive correlation between passive share in a given market and valuations, at least when expressed by the price-to-sales ratio.

Moreover, his data suggested that stock market corrections have become rarer and price declines shallower, which he attributed to passive investing creating “a steady buyer which can step in when investors’ sentiment sours”.

Drilling down further, cheap “value” and small-cap stocks have underperformed in the US since 2006, a reversal of the return premia that these two style factors have traditionally provided.

While other factors such as falling interest rates, which benefit growth stocks, could be responsible, Deluard argued the pattern may also be due to “continued outflows from the active sector, which tends to overweight” value and small-cap.

Within the size component, he found that buying the two largest stocks in the Russell 3,000 index at the end of every year had returned 411 per cent since 2014, against 143 per cent for the index as a whole, a reversal of “winner’s curse” that once prevailed, again potentially due, in part, to net purchases of megacap stocks as investors rotate from active to passive funds.

Deluard is no opponent of index-tracking funds per se, accepting that the passive revolution has brought benefits, such as investors “wasting less money on mediocre, overpaid active managers and their big distribution structures”.

However, he added that “on the volatility front I do liken it to forest fire management” — where policies that aim to stub out every small fire lead to a build up in combustible undergrowth that can lead to larger, more devastating conflagrations.

One potential criticism of his analysis is that, even without the advent of passive investment, the wall of money that has entered equity markets in recent decades would presumably still have done so via actively managed funds, meaning valuations in general might be just as high.

Deluard accepted this was a “logical argument,” but believed active fund managers “would try to deploy their cash more strategically. If you have higher inflows you don’t have to buy high, you can buy the dips. Passive will buy right away.

“Close to $1tn gone into ETFs in the past year. If you move that much money that quickly, that will have an impact on price,” he concluded.

Vitali Kalesnik, director of research in Europe at Research Affiliates, a pioneer in smart beta strategies such as value and small-cap, agreed that the rise of passive investors had had an “impact” on markets.

“By definition, they are not participating in price discovery. They are price takers. That definitely has consequences,” he said. “There are fewer market participants correcting for mispricing. This can lead to longer bubbles and increase the riskiness of contrarian strategies.”

Kalesnik also attributed the changes in the nature of markets to a rise in retail participation, which “has probably doubled in the last 15 years”, meaning more investors who are “prone to fads, overreacting to news and herd behaviour . . . increasing the chance of mispricing.”

However, Ben Johnson, director of global ETFs and passive strategies research at Morningstar, argued that index funds’ trading activity “accounts for a small minority of global trading volumes, so on any given day the hard work of price discovery is still being done by market participants with distinct views on securities’ intrinsic worth”.

“I think we are still a long ways off from any sort of tail-wags-dog type scenario, where index funds undermine the process of setting prices,” Johnson added.

“And if we do reach that point, the market will ultimately heal itself. New opportunities will arise for active market participants and the pendulum will begin to swing back in the other direction.”

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments