Oversupply of US debt leaves few takers for Treasuries

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

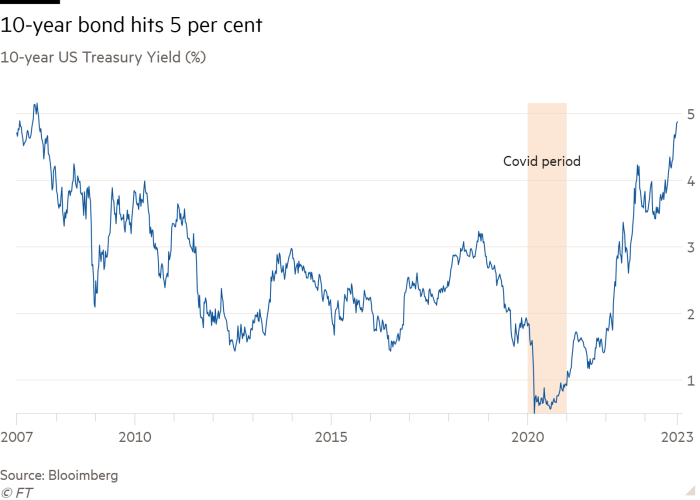

The US government’s huge borrowing plans have helped fuel a historic rout of Treasury bond prices, pushing their yields to the highest level since the global financial crisis and raising questions over whether there are enough buyers for all this debt.

Between August and October, the yield on benchmark US Treasuries jumped by a full percentage point, despite a growing consensus that the Federal Reserve was at, or close to, the end of its interest rate rising cycle.

Much of that move has been attributed to investors expecting US interest rates to stay higher for longer, in response to the unexpected resilience of the US economy.

But investors and analysts also suggest that a glut of new debt being issued in the US, to plug a yawning budget deficit, has also pushed yields higher.

And there are few signs of any political appetite to rein in government spending soon. According to the IMF, the US government budget deficit is on track to exceed 8 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product this year, and net borrowing is expected to remain elevated at 7 per cent of GDP in five years’ time. Between 1973 and 2022, the annual deficit had averaged 3.6 per cent of GDP, based on Congressional Budget Office data.

“The unsustainability of the fiscal framework is probably the biggest factor in driving this fear of bonds,” says Jim Cielinski, chief investment officer for fixed income at Janus Henderson. “Supply is shifting up at the same time as demand from price-insensitive buyers has dissipated — most noticeably from central banks.”

The Fed’s holdings of long-term debt securities already exceed $7tn and, as an end to its quantitative easing policy means it has stopped buying bonds to let existing bonds run off, a big source of demand for them has disappeared.

Investors have pinned the accelerating rise in long-dated bond yields to an announcement by the US Treasury department in August. It said it would issue as much as $1tn-worth of bonds in the three months to October, raising immediate concerns over who was going to buy them.

“You can discern a change in the bond market from the Treasury announcement and the big step up in supply, which was the real problem for bond yields,” argues Quentin Fitzsimmons, a senior portfolio manager at US asset manager T Rowe Price.

However, as US Treasuries have been the ultimate haven asset underpinning the global economy, investors say there will always be demand for them. The question is, simply: at what price?

Matthew Morgan, head of fixed income at Jupiter Asset Management, says he expects demand to pick up no matter how the economy plays out. “A soft landing is still good for debt as people will buy when they get clarity,” he says. “And a hard landing will be very good because bonds will catch a bid as expectation for rates go down.”

But figures on the US Treasury website show signs that some big investors have been retreating from the US government bond market. Ownership of US Treasuries by Japan, the largest foreign holder, fell by 6 per cent over the year to August, despite a slight pick up in recent months.

Similarly, Chinese buying, which had been strong over the past two decades, has stalled. Chinese ownership of Treasuries has fallen by 14 per cent since August, according to official US statistics, which analysts say is in line with Chinese investors not buying rather than actively selling.

“Big investors are less sanguine about the US Treasury market,” explains Christian Kopf, head of fixed income at Union Asset Management. “It doesn’t make sense for Japanese investors on a hedged basis and the Chinese have been pulling back too.”

Yet, while big investors hold back, asset managers and households have been loading up on US bonds. Analysis from Goldman Sachs showed that American households and hedge funds now own 9 per cent of the Treasury market, up from just 2 per cent at the start of 2022, with net flows on track for $1.3tn this year.

Even so, households remain big buyers of equities, suggesting that a rotation into Treasuries could have much further to run. According to Goldman, US households have a 42 per cent allocation to equities — one of the highest weightings since 1952.

Meanwhile, trend-following hedge funds — known as commodity trading advisers — have built up extreme short positions in Treasuries as prices have fallen, which could turn into buying momentum when Treasuries start to rally.

“Buyers will have to come a little from all corners, but I think it will be gradual,” says Peter Tchir, head of macro strategy at Academy Securities. “People have bought into Treasuries as yields are rising and I think there is only so much ‘new demand’, as people will want to be careful to maintain a balance between equities and fixed income.

“At the moment, it is easy to see supply overwhelming demand, but I think that fear is overdone.”

Comments