Mistakes to avoid when investing in Middle East and north Africa

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Middle East and north Africa (Mena) region is infamous among foreign investors for being difficult to understand. This lack of comprehension has created a risk premium far in excess of what is necessary for the region, leading to higher returns for informed investors.

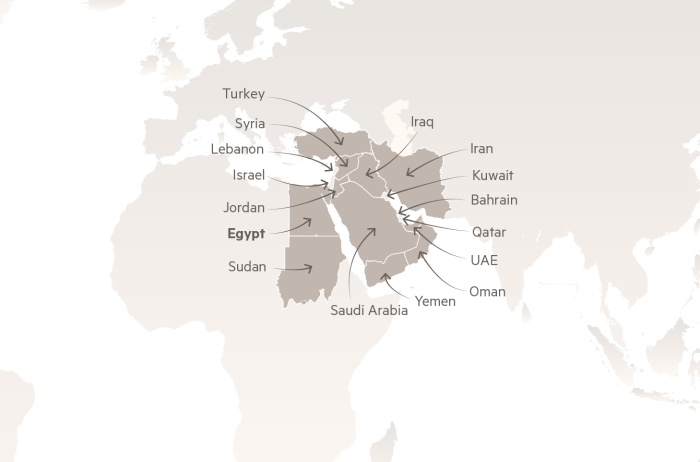

The first mistake is to assume that Mena, a collection of 20 or so countries, is homogeneous. Although most people in Mena identify as Arabs and possess shared traits — which lead to a larger market — the cultural and economic differences around the region are substantial.

While these differences create diversification opportunities, it also means that, for example, hiring an investment analyst from the Levant to analyse the Gulf states will not create any more value than hiring someone who grew up in Britain.

The second mistake is to misunderstand communication, which in the Arabic speaking world is relatively indirect and more non-verbal than the Anglo-Saxon style. The divide is marked in the Mena region because foreigners often confuse fluency in language with compatibility in communications.

Speaking generally, Arabs do not like to use the word “no” but that does not mean that they do not say “no”. The failure to grasp such nuances has broken the careers of many foreign businesspeople in the region.

In 2001, I was the lead founder of Saffar Capital, a Mena private equity group. Our first investment, driven largely by the insights already mentioned, was a finance media company. The investment was successful mainly because we did not adopt the Silicon Valley myths that are now being imported into Mena and which hobble local start-ups and destroy investment value.

The first myth we ignored was that we needed local entrepreneurs. Zawya, our investment, was founded by British citizens of Iraqi descent and based in London. However, we immediately moved the company and its five full-time employees to Dubai and ensured that our investment group — with its deep knowledge of Mena — complemented Zawya’s founder team.

We broke a second taboo by refusing to allow the founders to manage the company whilst controlling the votes. The idea that an entrepreneur can maintain equity control of their company exists in the US only because the supply of investment far outstrips the demand. In much of the rest of the world the opposite is true, and Mena entrepreneurs trying to keep control of their companies and fund them externally will find there is little appetite for that approach from local investors.

The third myth we sidestepped concerned the idea of trying to solve a regional problem. That is self-limiting. The problem we solved was global: how foreigners perceived and digested Mena financial news and data. Instead of seeing the region’s often volatile news events as a challenge, we exploited them as an opportunity.

By using an online platform, we sidestepped many of the regulatory problems that a physical presence such as local offices and production would have faced. Other start-ups such as Maktoob (bought by Yahoo), Souq (bought by Amazon) and Careem (bought by Uber) also used digital platforms to overcome the multi-jurisdictional issues of Mena.

The fourth taboo we broke was being commercially driven rather than emotionally passionate. Again, you can be passionate if investment demand far outstrips supply, but when this is not the case, entrepreneurs must think commercially. We also focused on margin growth as a key indicator of performance, rather than revenue growth.

The fifth taboo is location. Entrepreneurs are too enamoured of being “where it’s happening”. In Dubai in 2002, this meant the hubs of Dubai Internet City and Dubai Media City. We instead chose to set up in Deira, the old town, for less than one-third of what it would have cost in one of the hubs. Our research team, comprising three-quarters of Zawya’s employees, were based in Beirut, where skilled, educated, hardworking professionals are abundant and reasonably remunerated.

The sixth taboo is the timeline. In Silicon Valley, entrepreneurs may be able to generate investor returns in a few years. It took six years for Careem to exit, 10 years for Maktoob and 12 years for Souq. It took us 11 years to build Zawya and sell it to Thomson Reuters.

We generated a 35 per cent cash internal rate of return — a closely watched measure of performance — on Zawya over those 11 years. We made our investment in November 2001, right after the September 11 2001 terror attacks that sent the Mena equity risk premium skyrocketing.

We did not invent anything new, we simply executed better than our competitors, including global giants. In 2004, we used the same principles to build a Saudi investment bank and later sell it to Credit Suisse.

The main challenges to venture capital investing in Mena are not a dearth of funding and skilled employees, but simply overcoming a lack of regional expertise.

Sabah al-Binali is an investor and entrepreneur with a record of financing, building and growing companies in the Mena region

FT Future 25: Middle East

Supported by

Comments