What London’s falling population means for the housing market

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For the first time in 30 years, London’s population is falling. Coronavirus has stemmed the flow of migrants into the capital and created new reasons for residents to depart. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, almost 700,000 foreign-born residents may have left the city, according to one estimate by the government-funded Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE).

The loss — which at that level would be equal to about 8 per cent of London’s population — is already being felt in the city’s property market. Rental prices in inner London have fallen sharply since the start of the pandemic, and the number of property sales in the capital’s prime, central areas has dropped as international buyers have been kept away.

But will this be a shortlived dip, or something more sustained? With the vaccine rollout under way, some experts think that overseas renters and buyers will return in droves once shops and businesses can reopen.

Others believe that underlying economic conditions, coupled with the impact of Brexit, point to a longer-term reduction in demand for London property, creating a drag on house prices that could last beyond the end of the pandemic.

So what is next for the London property market? We took a look at

the evidence.

Exodus leaves rentals reeling

Teresa Gottein Martínez left London for Spain in February, when the severity of coronavirus started to become clear. “I and many people I know went back to our home countries during Covid, be it to be in lockdown with family rather than alone, or to save money on rent,” says the 24-year old freelance writer.

Some leavers — including Martínez herself — have since returned, drawn by work or the pull of a city which, despite being diminished, remains home.

But with job loss one of the major factors behind the departure of foreign-born Londoners, others have not, and are unsure they ever will. Martínez says that one friend has begun looking for work outside of London after losing her job there. “We all need to pay our bills somehow, even if it means moving countries,” says Martínez.

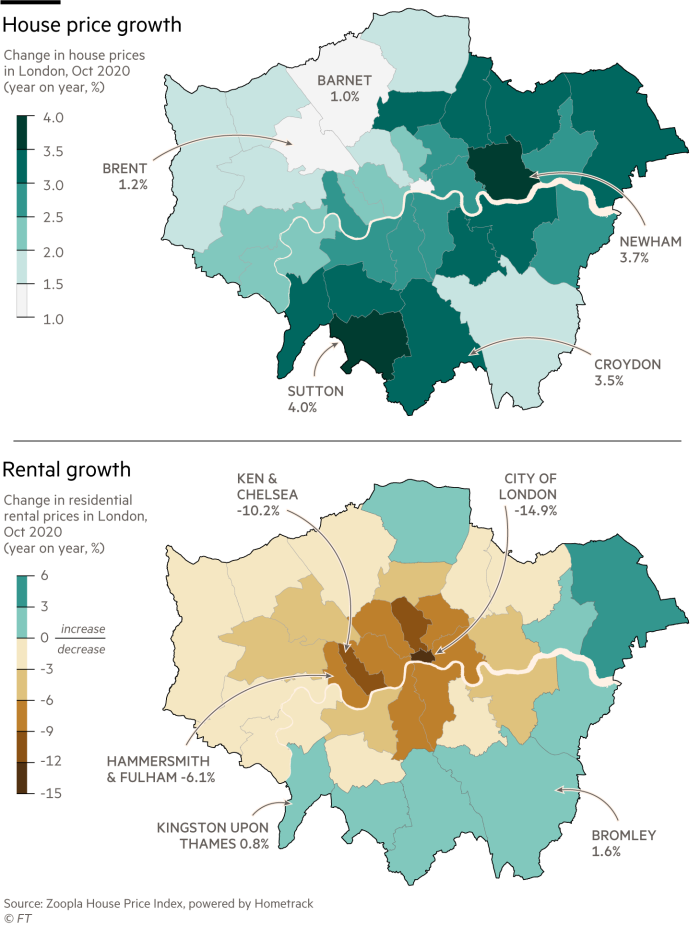

Their absence is already being felt in the rental market. In the 12 months to October, average rents in London fell 6.9 per cent, according to property portal Zoopla. In Kensington & Chelsea, which is home to some of the capital’s most expensive property, the average rent dropped 10.2 per cent. In the City of London, it fell 15 per cent.

Met with a sharp drop in demand, some landlords are having to slash prices to appeal to tenants. Across central London, reductions of more than 25 per cent have become relatively common, according to homes listed for rent on Zoopla. A one-bedroom flat near Piccadilly Circus has recently cut its asking price by 43.8 per cent to £1,950 a month.

What next for house prices?

London house prices have grown since the first lockdown ended, especially in the outer boroughs, as lockdown-weary buyers look for more space and their own garden. Since July, property sales have been boosted by the government’s stamp duty holiday — which waives the charge on the first £500,000 of any home purchase until March 31, saving buyers up to £15,000.

But how much have they grown? Official figures published on Wednesday by the ONS and drawn from Land Registry data, suggest that London prices rose by 9.7 per cent in the year to November, to an average of £514,000.

But Richard Donnell, research director at Zoopla, says Land Registry data has been volatile recently, due the fact that more expensive houses have been selling, rather than flats. In the year to October, for example, ONS figures show that prices rose 3.9 per cent to £491,000 — a £23,000 increase in the average value of a London home in the space of a month seems unlikely, Donnell says.

Zoopla’s house price index for November suggests that the price in London had grown by just 3 per cent in the previous 12 months, with boroughs such as Merton and Sutton showing the largest gains.

However much prices rose last year, tremors in the rental market could soon start to be felt in the sales market, says Neal Hudson, a UK housing market analyst.

“If rents are falling that will put pressure on landlords: gross yields were already quite low in parts of London and if [landlords] have got any sort of debt they are unlikely to be covering costs.”

That could trigger a raft of non-profitable buy-to-let properties hitting the market at the same time, which would put downward pressure on local house prices. “We could definitely see that happen, particularly in new-build markets such as Nine Elms,” says Hudson, referring to the huge redevelopment project near Battersea Power Station on the south bank of the Thames.

Meanwhile, the loss of thousands of tenants will affect future sales too, says Donnell. “The rental market is the top of the funnel: the number of first-time buyers in London tomorrow could be hit by a lack of activity in the lettings market today,” he says.

A swift rebound in population — which would restore demand for housing — depends on the return of the departed masses. But even if the pandemic is contained, tens of thousands of jobs lost in the hospitality sector, where foreign labour is a considerable part of the mix, will not return overnight.

“We’ve all but switched off the flow of people coming from abroad,” says Hudson. “There’s fewer international people coming in, including students. So even if the numbers leaving are consistent, that would mean the population is seeing some pressure.”

But the numbers are not consistent. A new points-based immigration system, introduced post-Brexit, has added to the barriers facing migrants from the EU, and is expected to lower the numbers moving to London in the longer-term.

Meanwhile, the number of Londoners departing the city and buying homes elsewhere has increased. Estate agency Hamptons International estimates that departing Londoners bought 73,950 homes outside the capital last year, the highest number since 2016 — and the highest proportion of sales outside of London since before the financial crisis.

“Proportionally, the share of homes outside the capital that were bought by a London leaver reached 7.5 per cent, the highest level since 2007” [when it was 8.2 per cent],” says Aneisha Beveridge, head of research at Hamptons.

One of those leavers is Elysia Byrd, who is painting the walls of her new home when she answers the phone. The 31-year-old and her boyfriend bought the house in Hastings, on the UK’s south coast, in December, leaving behind a rented flat in London.

“We’re both artists and we were living in a flat in Crystal Palace with no garden and one bedroom. We just thought, ‘What are we doing?’ Now we’ve got a studio and I can see the sea,” says Byrd, who grew up in London. The couple never thought they could afford to buy in London; the pandemic, she says, “gave us the impetus to leave”.

As 2020 has underscored, putting a firm figure on what the exodus means for house prices a year out is impossible. The grim expectations at the start of the pandemic last year were confounded by government intervention and shifting buyer preferences.

Ministers may act to support the housing market again in 2021, and historically low interest rates look likely to burnish the appeal of property for some time yet. Even so, estate agencies are anticipating very limited price growth this year.

Betting long on central London

Many buyers have been happy to look beyond what they believe will be temporary effects of the pandemic and have bought homes in central London. Anita, a solicitor, has just completed on a one-bedroom flat in The Denizen, a new development near the Barbican in the City of London, after renting nearby for seven years.

“I work crazy hours and wanted to be able to walk to work in 15 minutes,” says 31-year-old Anita, who did not want to give her real name. “I am sceptical that the working from home trend will continue and think the City will get its buzz back.”

Others, having sampled a different lifestyle in the countryside, found it only renewed their urge to be in the capital. “We had a chocolate-box thatched property with plenty of land and nobody around but I felt isolated and uninspired,” says fashion designer Stephanie, 41.

“It was complete cultural shock. I missed cosmopolitan London. There was nowhere to go aside from the village pub.” Stephanie and family only moved to south Oxfordshire two years ago, but are now living close to Hyde Park in a three-bedroom flat.

Those who are wealthy enough can choose to have a foot in each camp. This group “don’t want to cut themselves off from London life completely, as moving to the country is a big adjustment. One buyer moved out to a big pile in Surrey but is so bored she started renting a room at Claridge’s three nights a week [until Tier 4 restrictions ended this in December],” says Martin Bikhit of Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices.

Eroding the London premium?

While ONS figures show London prices zooming ahead, according to Zoopla, house price growth in London last year was slower than nearly every other UK region. Spurred on by the stamp duty cut, prices in the North West grew 5 per cent; in the South West, they rose 3.6 per cent.

After the stamp duty holiday ends on March 31, most estate agents predict a sharp drop in activity. In London, the impact will be greater if the city’s population continues to contract. According to a paper by independent research house Carraighill, which analyses the effects of the new points-based migration system on the housing market, that is a real possibility.

“The points-based system creates legal and bureaucratic hoops which migrants now have to jump through . . . that’s pushing a lot of lower-skilled EU migrants out of contention,” says David Higgins, the report’s author. “A slowdown in migration will slow house-price growth in London and that will spill out to the south-east and south-west: if you want to sell but there’s no migrants to buy there will be an impact.”

House & Home Unlocked

FT subscribers can sign up for our weekly email newsletter containing guides to the global property market, distinctive architecture, interior design and gardens. Sign up here with one click

The ONS forecasts that the UK’s population growth will slow over the course of the next decade. “But 2020 and 2021 are likely to bring sharper drops,” says Higgins. “That’s dramatic for a country that’s enjoyed strong population growth since Thatcher’s time.”

That could mean that a period of relatively slow growth for London’s property prices — during which prices in other regions of England have been catching up — is extended.

“In pound sterling terms, prices in London have gone sideways, and in real terms have gone down for the past six years. What you’ve really seen is a soft correction in London,” says Donnell.

A slowdown or a dip in prices would be bad news for homeowners, who could struggle to trade up the property ladder, or even find themselves in negative equity. But, says Hudson, “it could actually be what London needs over a longer-term perspective, if it leads to London becoming more affordable and more attractive to young people again.”

Additional reporting by Liz Rowlinson

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

This article is has been updated from the version that appears in print to include reference to new ONS house price data

Comments