A year of pain: investors struggle in a new era of higher rates

Simply sign up to the Capital markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

One year ago, Jay Powell threw out the rulebook global investors had used for over a decade.

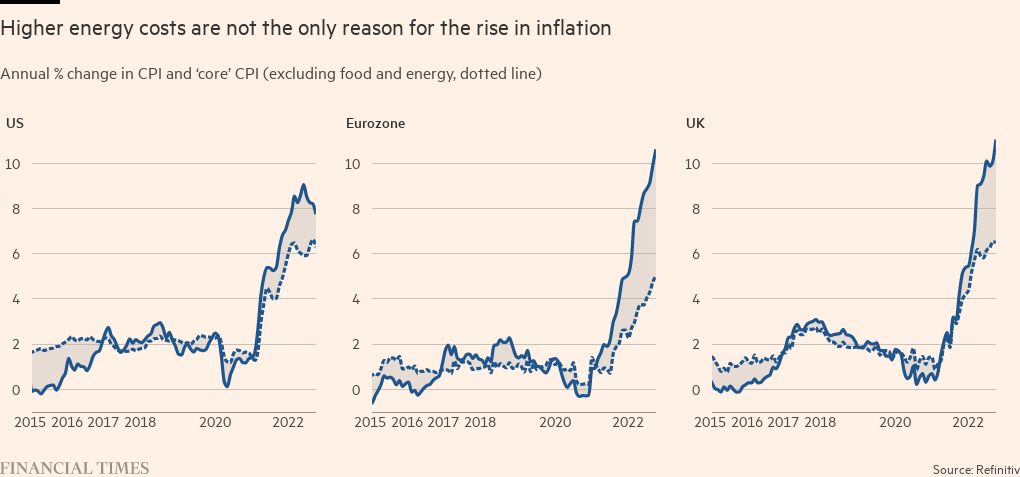

Long dormant inflation had been picking up as pandemic lockdowns eased, but for months central bankers such as Federal Reserve chair Powell had urged households, businesses and investors not to panic. The rapid burst of price increases, they insisted, would prove transitory.

But on November 30 2021, Powell publicly accepted that assessment might have been wrong. Speaking at a congressional hearing, he said inflationary pressures were “high”. The annual rate was running at 6.8 per cent at that point, far above the Fed’s 2 per cent target. Ending the Fed’s stimulative bond purchases might need to accelerate, he said. “It is appropriate in my view to consider wrapping up the taper of our asset purchases . . . perhaps a few months sooner.”

To the untrained eye, this might seem like a routine observation. But looking back, it rang the bell at the top of the market, which had rocketed since central banks stopped them from bleeding out when Covid-19 struck. Powell was effectively calling time on an entire era of super-cheap money that began after the 2008 financial crisis.

Bonds and stocks quickly started falling because for the first time since the crisis, Powell had embedded the notion that interest rates would need to climb, forcefully, and that central banks would remove the bond-buying safety net that many fund managers took for granted. One year on, investors are still learning to live with the reality of higher interest rates and low returns for the long haul.

Some investors have a bleak outlook for the coming years. “We’re now going through a period which is payback time,” says Nick Moakes, chief investment officer at the £38.2bn Wellcome Trust, one of the UK’s largest endowment funds. “We’ve borrowed future returns, we’re going to pay them back now.

“The key thing is to make sure we’re in a position in our portfolio to cope with an extended period of sub-par returns because we’ve had this extraordinary period since 2009,” he says. “Whereas in the last decade we delivered real returns of 11 to 12 per cent a year after inflation, delivering 1 per cent real returns a year after inflation over the next decade would not be an implausible outcome.”

Powell could not have known that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine three months after his remarks would supercharge inflation through commodities prices and make his task, and his stance, much tougher in 2022. But the paradigm shift he signalled one year ago has formed a key factor in a massive reset in markets.

“This has been a year to be in the bunker,” says John Bilton, head of global multi-asset strategy at JPMorgan Asset Management.

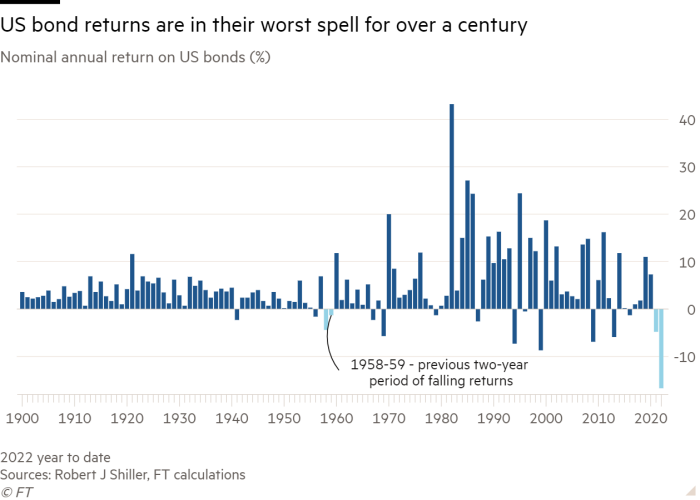

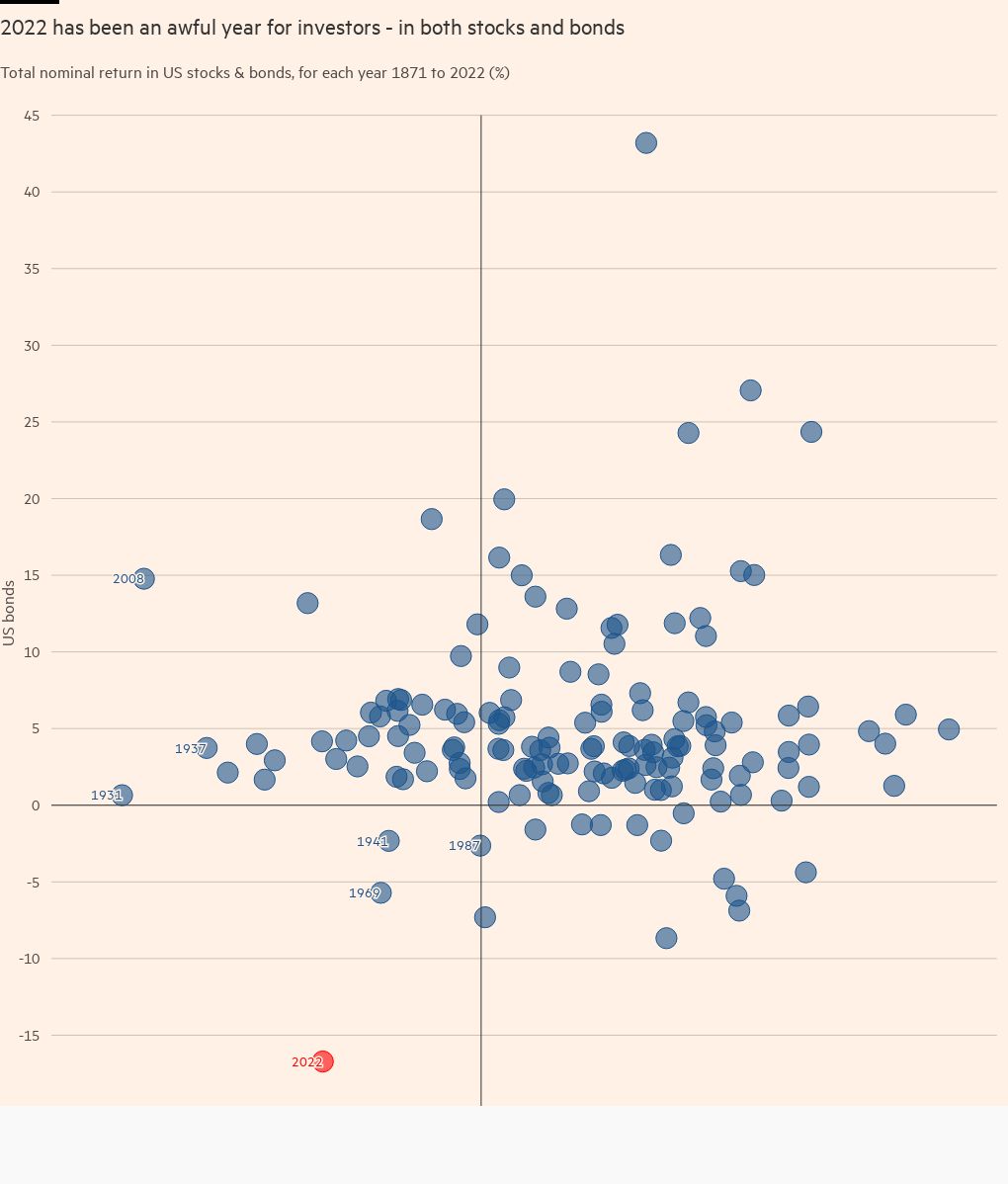

Long-term US government bonds staged the biggest drop since 1788. Investors’ classic blend of bonds and equities has put in the worst performance since 1932. At its lowest point this year, the S&P 500 index had shed $11tn in market capitalisation: to give an idea of the scale, even if the figures are not directly comparable, that is similar to the entire annual economic output of Germany, Japan and Canada combined. Tech stocks alone have lost an amount equivalent to the output of France or the UK.

That combination of wilting stocks and bonds has made the task for fund managers safeguarding people’s pensions and savings even worse. It left nowhere for them to hide.

“Powell gave the signal that squashed everything,” says Emiel van den Heiligenberg, head of asset allocation at Legal & General Investment Management. “The positive correlation between stocks and bonds . . . is not a black swan,” he says, but fund managers have never known it to last this long.

“This environment is kryptonite for multi-asset investment,” he adds. “For long-only investors it has been an extremely frustrating year. Out of the 25 asset classes we cover, only one, commodities, has been positive.”

Few investors would argue that the Fed, and its peers elsewhere, have been wrong to try and dampen inflation. After all, soaring costs for goods and services hurt living standards for everyone, whereas asset price declines primarily damage wealthy asset owners.

Once established, inflation can also quickly infect economic systems as it pumps up expectations for further price rises. That drives workers’ demands for higher wages, which, if honoured, can push up costs for businesses further. In June, the Bank for International Settlements — often known as the central bank for central banks — said big economies were close to a “tipping point, beyond which an inflationary psychology spreads and becomes entrenched”.

Many fund managers complain that central bankers could and should have got to grips with the issue sooner, rather than extending the support that was essential when the pandemic first struck. Instead, policymakers were wrongfooted as they continued to fight the last battle.

“We thought at the time [of Powell’s comments in November 2021] they had finally woken up to something we had seen for many months,” says Andrew McCaffery, global chief investment officer at Fidelity International. “They weren’t telling us anything new, just finally getting round to the point of recognition.”

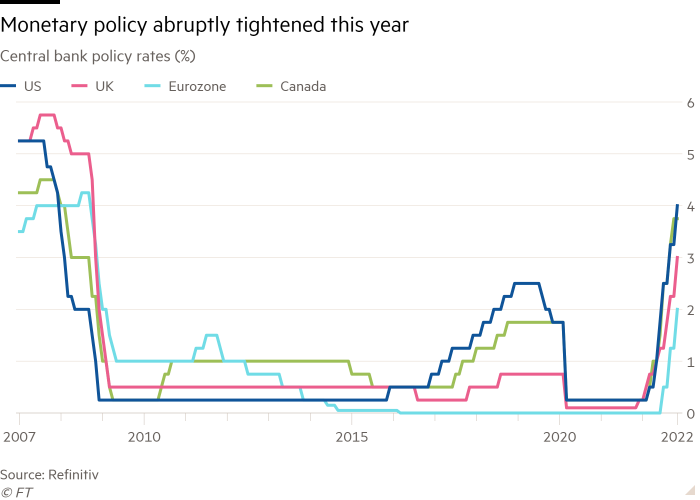

But neither policymakers nor fund managers can turn back the clock. Instead, asset allocators are learning to live with a much more challenging environment while the Fed all year has layered one supersized rate rise on top of another and started to chip away at its $9tn balance sheet stuffed with stimulus-era bond purchases. The European Central Bank and the Bank of England have also turned off the taps, leaving only Japan and China among the big economies where rates have remained supportive.

The biggest change from global tighter monetary policy is that bond yields have screamed higher. That means fund managers have had to sharply mark down the value of the existing bonds they hold. It also means the case for investing in risky assets has been seriously dented. Why bother taking a chance on a hot company, particularly one that is not yet profitable, when yields on some of the safest assets on the planet — US government bonds — have tripled?

Some investors welcome this new discipline. “This has been a train crash waiting to come,” says Alexandra Morris, chief investment officer at Norway’s Skagen Funds. “Now, money has a cost. You can’t just throw money at unprofitable businesses, very risky businesses. We need to have a much more sensible allocation of capital.”

John O’Toole, global head of multi-asset investment solutions at Amundi, Europe’s largest asset manager, also says the past year has comprehensively shaken up how he looks at bonds. “Look at just how much of a freak show we have been living through. Rates have been at zero for seven years. We had rates at emergency levels for years and years,” he says.

At the peak in 2020, interest rates were so low and bond prices were so high that some $18tn in government bonds around the world came with yields below zero per cent, giving new buyers a guaranteed loss if they held to maturity.

“Fixed income was an uninvestable asset class — think how extraordinary that was when we had negative yields. All bets were off. Now bonds are investable again,” says O’Toole.

One big difference for investors now is that the safety net from central banks — their ability to roll out rate cuts and bond purchases that prop up markets whenever trouble hits — is simply not possible in this new era of inflation.

Some of the drivers of low inflation, like improving technology, remain in place. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the cost of funding a green energy revolution and the challenge of pulling some manufacturing out of China all mean higher prices are likely here to stay. If nothing else, central banks have made it very clear this year that they intend to do whatever they can to tame prices, even if that means engineering an economic slowdown and higher unemployment.

Nobody knows for sure what, if anything, can break the spell for fund managers, whether next year will be meaningfully brighter than 2022.

Over and over again this year, investors awash with cash they are itching to deploy have demonstrated an intense urge to sound the all-clear. Every hint of possible weakness from central bankers, every sign that inflation might finally be cooling, have sparked a series of rallies.

March, June and October this year have all produced rallies greater than 10 per cent in global stocks for precisely that reason, ranking them among the biggest so-called bear-market rallies — pushes higher in broadly weakening markets — since 1981, according to analysis by Goldman Sachs. This summer’s ascent lasted two months, one of the longest rallies in that near 40-year period.

It did not last, however, not least because Powell upped his rhetoric against inflation sharply at the annual get-together for policymakers in Jackson Hole in August, saying the Fed “must keep at it until the job is done”. Goldman Sachs advises clients that this latest pick-up probably will also stumble.

“The bear market is not over, in our view,” wrote Peter Oppenheimer and colleagues at the US investment bank in its outlook for 2023. “The conditions that are typically consistent with an equity trough have not yet been reached. We would expect lower valuations, a trough in the momentum of growth deterioration, and a peak in interest rates before a sustained recovery begins,” the bank said.

Research house TS Lombard also points out that none of the US bear markets observed over the past century has ended before the recession related to it has begun. The widely anticipated US recession has certainly not landed yet.

Tatjana Puhan, deputy chief investment officer at French asset manager Tobam, thinks any optimism is misplaced. “To be honest, I’m surprised how positive markets are,” she says. “I’m surprised how little the market realises how far the Fed might go, how little investors care about monetary credibility. This is what it’s about. To me it seems like investors are still too positive about every little piece of positive news.” She is expecting stocks to fall at least around another 10 per cent.

It is not only monetary policy that can still inflict pain. Equities are not even close to reflecting the risk of a deep, ugly US economic recession that could come around and pulverise corporate earnings next year, many fund managers say.

Even so, investors with a long horizon are convinced now is the time to fill up portfolios with beaten-up stocks and bonds. The classic portfolio mix — 60 per cent stocks, 40 per cent bonds — now has the best outlook in a decade, says Grace Peters at JPMorgan Private Bank. “The valuation froth has come out of risk assets so this is a good point to rebuild portfolios for the longer term,” she says. “Stay invested. It is always darkest before the dawn.”

Looking at data going back two decades, says Peters, it is clear that hopping out of stock markets and hopping back in just at the right time is hard. Sticking in the S&P 500 all that time would have delivered annualised returns of 9.76 per cent, but missing the 10 best days would slash that annualised return to 5.6 per cent. Missing the 30 best days cuts it to 0.8 per cent.

The bet for next year appears to be that stocks will keep falling at the start of 2023 as recession bites, but then stabilise somewhat or even recover. Bonds are broadly expected to do a better job of balancing out any pain, now that juicy yields provide a thicker buffer. That, says Morris at Skagen, is much more of a “normal cycle” than we have seen for at least the past decade and a half.

The danger, though, is that investors will keep on tripping up over assumptions that simply do not work in this new era.

Data visualisation by Keith Fray and Eade Hemingway

Comments