US interest rates add to ‘silent debt crisis’ in developing countries

Simply sign up to the Emerging markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Many smaller emerging markets are confronting a “silent debt crisis” as they struggle with the impact of high US interest rates on their already-fragile finances, the World Bank has warned.

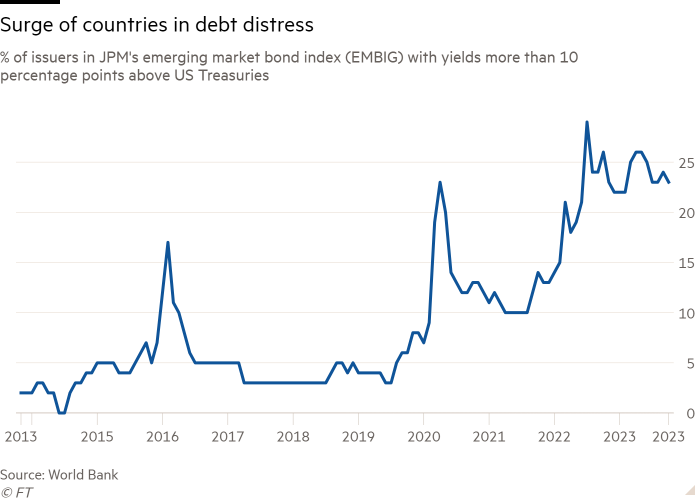

After a sharp sell-off last year triggered by a rapid rise in global interest rates and a strong dollar, foreign currency emerging market debt has struggled to recover as investors bet that borrowing costs will have to stay higher for longer.

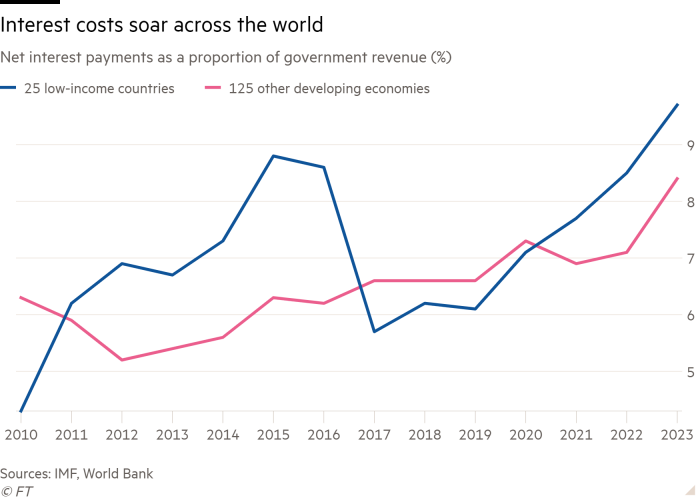

That has left the proportion of emerging and developing countries whose borrowing costs are more than 10 percentage points above those of the US at 23 per cent. That compares with less than 5 per cent in 2019, the World Bank calculates, in an indication of the stress those economies are now under.

As a result, debt interest payments as a share of government revenues were at their highest level since at least 2010, according to the bank.

The monetary policy tightening cycle had been a “nightmare” for lower-income countries with high levels of debt, said Ayhan Kose, deputy chief economist of the World Bank Group in an interview. “Given the well-defined challenges these economies are facing with respect to rolling over debt obligations . . . we are saying there is a silent debt crisis that has been taking place.”

The pain from higher borrowing costs is expected to be particularly acute for lower-income countries, given that many of them ran up large debt piles during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Higher yields mean larger interest payments on freshly issued debt, which can force up debt-to-gross domestic product ratios if governments borrow more to fund those payments. Bond yields move inversely to prices.

Emerging market and middle-income countries’ average gross government debt burden is heading above 78 per cent of GDP by 2028, according to IMF forecasts, compared with just over 53 per cent a decade earlier.

Whereas many of the biggest emerging economies have weathered higher borrowing costs relatively well, smaller economies with more fragile finances have struggled.

The rise in yields has also shut off many low-income countries from international financing, pushing the likes of Ghana and Sri Lanka into default and leaving many others on the brink.

A subset of weaker emerging and developing countries “have been just priced out of the dollar bond market”, said Brad Setser, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. “It’s an environment where only the stronger emerging markets can afford to borrow in dollars.”

Higher for longer

This is the fourth in a series of articles about the impact of high interest rates across businesses, governments and economies around the globe.

Part 1: Private equity takes a hit

Part 2: Government finances and the impact on markets

Part 3: Reverberations in the corporate world

Part 4: The consequences for emerging markets

Part 5: Implications for asset management

If rates stay higher for an extended period, borrowing costs are likely to bear down on economic growth, say analysts, making it harder for economies to grow out of their debt stresses. That is particularly worrying for countries such as Egypt and Kenya, which each have bonds maturing next year and face the difficult prospect of trying to refinance at higher yields.

“Higher costs to finance will over time weaken fiscal deficits, so countries will need to tighten their belts to avoid having their debt ratios rise,” said Lucas Martin, fixed-income sovereign strategist at Bank of America, noting that this could be complicated in countries where there is fatigue over austerity measures.

Higher US interest rates also reduce the ability of emerging economies to cut their own rates even when domestic inflation has fallen, as this could weaken their currencies, leading to inflation through higher import prices.

Several emerging economies were much faster to react than western central banks to the threat of inflation in 2021 and have already started cutting rates. But countries including Hungary and Chile have slowed the pace at which they are cutting in recent months, partly to support their currencies in the face of higher US rates.

The volume of foreign currency debt issued in emerging markets has slumped dramatically over the past two years as the cost of borrowing has soared. Emerging markets have issued about $360bn of foreign currency debt this year, according to Dealogic, following total issuance of $380bn in 2022. That follows issuance of between $700bn-$800bn in each of the previous three years.

Issuance has been hit by a lack of demand, as investors favoured issuers with high credit ratings, and waning supply as many sovereigns with low credit ratings lost market access during the rapid increase in US rates of the past 18 months.

“It’s a textbook environment for investors to hunker down and move capital toward the US and de-risk in EM and other asset classes,” said Paul Greer, emerging market debt fund manager at Fidelity. “Higher yields means more expensive issuance, unless you really need to borrow you can be a bit tactical and wait for lower yields to issue.”

Comments