‘New climate reality’ stretches global freshwater supply

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As Pere Aragonès, Catalonia’s regional president, declared a drought emergency across the Spanish region in February, he issued a stark warning: “We are entering a new climate reality.”

With water reserves falling to below 16 per cent of usual capacity in Barcelona and the local area, a string of restrictions — including limits on swimming pool use, a ban on watering public parks, and a reduction in agricultural irrigation — were rolled out. They are due to stay in place for more than a year.

Aragonès, who said some areas had not experienced rain in three years, warned that droughts are set to become more intense and frequent as global warming bites. But he added: “We will overcome the drought thanks to collaboration, shared effort, planning and well-directed investment.”

It is now a problem being experienced around the world: officials having to cope with water scarcity — and drought — as global temperatures rise.

Cities from Cape Town in South Africa to Chennai in India have faced severe water crises in recent years, as a triple whammy of population growth, industrialisation, and climate change put their water supplies under unprecedented stress.

About half of the world’s population already experiences severe water scarcity for at least some part of the year, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

It has led the UN to warn that the world is now “careering towards a global water crisis”, with a 40 per cent shortfall in freshwater resources predicted by 2030. Only about 3.5 per cent of the world’s water is freshwater, mostly held in glaciers and groundwater.

“The quantity of the water we have freely available for our use, and the quality of water available for our use, is heading in completely the wrong direction,” says water security, risks and economics expert Cate Lamb.

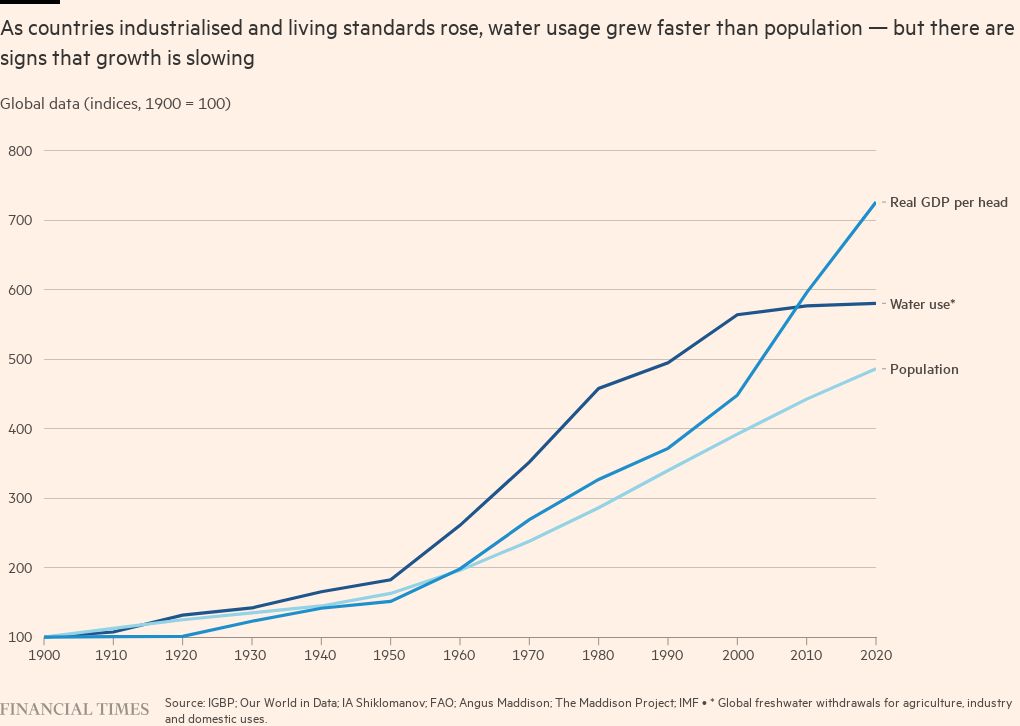

Stefan Uhlenbrook, director of hydrology, water and cryosphere at the WMO, says water demand is “outpacing the availability of water”, with climate change only reinforcing this problem. Climate change exacerbates both water scarcity and water-related hazards, from floods to droughts, he explains. This is because it changes rainfall patterns, disrupting the entire water cycle.

Uhlenbrook says that drought and flooding are becoming “more severe” because of climate change. Heavy rainfall can be too intense for existing water defences to hold, while flash flooding and so-called run-off affect the quality of fresh water.

Mina Guli, chief executive of water non-profit Thirst, says problems around water availability, pollution, and access have long been an issue, but climate change is acting as an “accelerant”.

“With climate change, water is falling in ways that we can no longer capture it,” she says. “So we’ve got more droughts. We’ve got more floods. And when it floods, the water goes straight out to the ocean and we don’t collect this.”

Rain, meanwhile, is falling in places where there are no dams or reservoirs, where people are not “equipped to actually manage and collect that water”, Guli adds.

“What’s happening now is that the water that’s available to us to use is decreasing, and that demand is increasing. And, therefore, we have a massive water challenge.”

Belgium, for example, is one of the countries suffering the most from water stress in Europe, according to the World Resources Institute, even though it experiences frequent rainfall. The country’s sources of freshwater are struggling to meet the demands of the country’s population, as well as heavy agricultural and industrial usage.

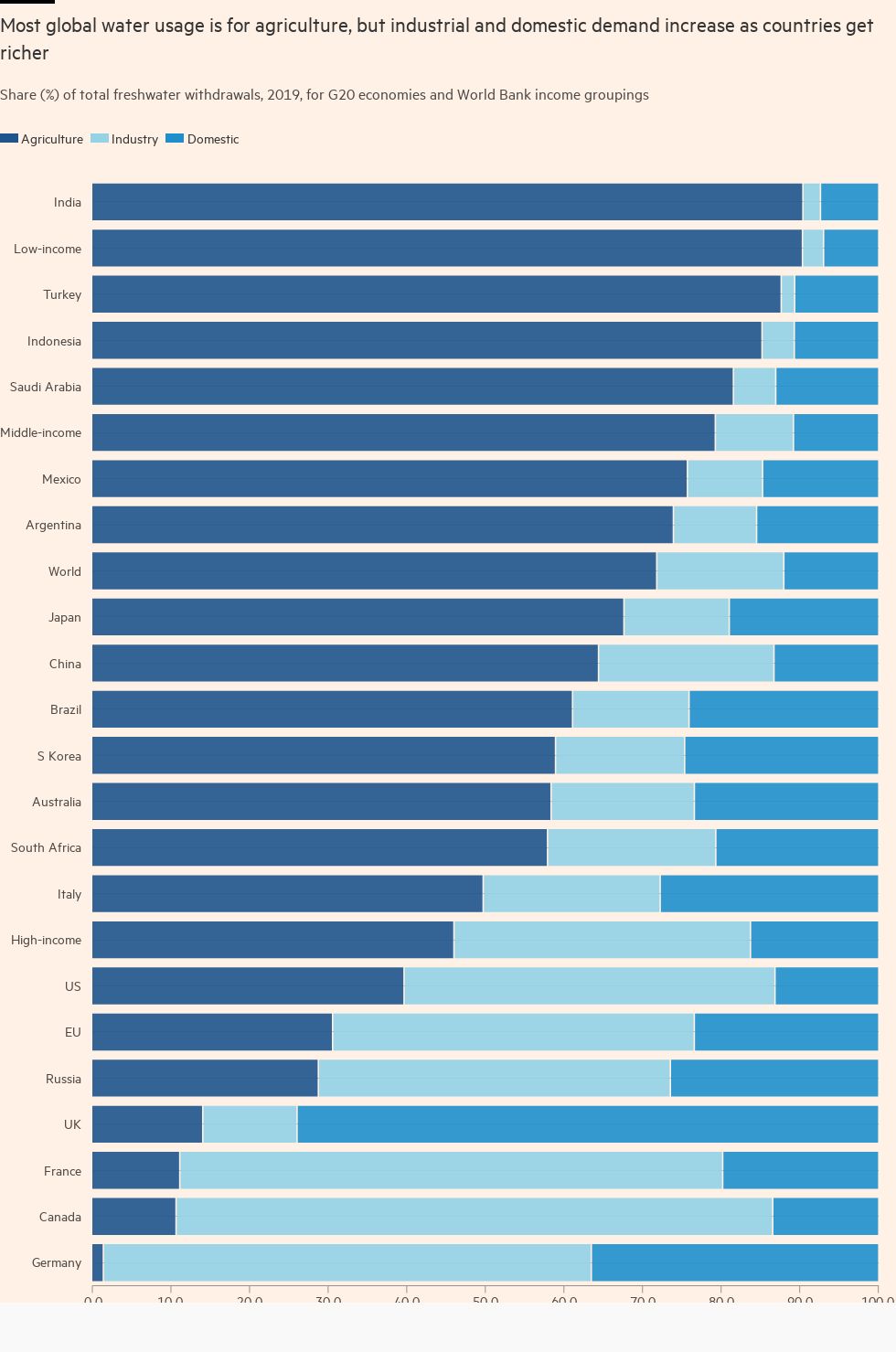

Climate change also means higher temperatures, resulting in an increased demand for water for activities such as crop irrigation. Agriculture and food production is by far the largest user of water, accounting for about 70 per cent of freshwater usage.

Another 20 per cent of freshwater is used in industry, with just 10 per cent used domestically, Uhlenbrook adds.

“Water goes into everything we use, consume or buy every day,” says Guli, citing clothing as an example: to make one outfit, she says, requires more water than a person would drink in 40 years.

While water scarcity can result in domestic restrictions, agriculture and industry will also increasingly feel the pinch, she warns. “It is the one thing that can decimate supply chains.”

Already, water levels in the Rhine river in Europe have been so low that barges vital for transporting goods have struggled to run. And, in France, some nuclear power plants have been forced temporarily to reduce output because of a lack of water for cooling.

“This is not just an environmental challenge,” says Guli, “It is an economic and commercial risk. It is a supply chain risk. Businesses and investors have failed to appreciate the enormity and scale of the challenge we are facing [when it comes to water].”

At the same time, water is often not a key focus of governments, says Durk Krol, executive director of industry body Water Europe. It is often seen as an environmental, or sometimes an agricultural, issue. But it is rarely the key focus for politicians in charge of those areas, he argues.

“In order to solve the water crisis, we need to make politicians responsible,” Krol says. “Then we need a strong water strategy for Europe. Then, we need an action plan.”

In Europe, a “Blue Deal” for water is potentially on the cards, akin to the EU’s climate-focused Green Deal. “The strong case we can build for water is the economic case,” says Krol.

Water pricing could help “steer the behaviour”, he adds, but this can be an “extremely sensitive topic”.

Guli argues that, to tackle water scarcity globally, we need to look at ways of using water more efficiently. “A huge amount of water is wasted,” she says. “Water doesn’t come from a tap, water comes from an effective ecosystem.”

Scientists and water experts say there are a host of solutions to tackle water shortages and achieve the UN’s vision of Water for Peace — its theme for today’s World Water Day. “On the whole, technologies and solutions already exist,” says Lamb.

For agriculture, this includes targeted irrigation, as well as sowing crops or seeds better able to cope with less water.

“We need to radically shift our agricultural practices,” says Lamb. “We need to clean up our act and stop the vast majority of significant pollutants entering our waterways. We need to increase our water efficiency . . . We need to ensure there is consistent monitoring at every level of the economy — national, local, businesses, financial institutions — to make sure we are not taking more than we can sustain.”

Some businesses are waking up to the challenge, she notes. Recently, Spanish bank BBVA issued a loan to electric utility company Iberdrola where the rate of interest was linked to specific water indicators.

Uhlenbrook says “more investments are necessary to adapt and minimise” water scarcity and drought, including more water storage.

Back in Barcelona, David Mascort, the minister for climate action in Aragonès’ government, says the region is investing heavily in solutions for its water crisis, including in desalination plants.

Yet, even in the middle of the winter, Barcelona could not avoid a drought emergency. “Due to changes in climate, it’s already super dry there [in Barcelona] in January, February, and the summer still has to come,” says Uhlenbrook.

What is happening in Barcelona will be replicated around the world, he warns. In other cities, too, “it is going to happen more frequently.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments