Banks set to move fewer than 4,600 City jobs over Brexit

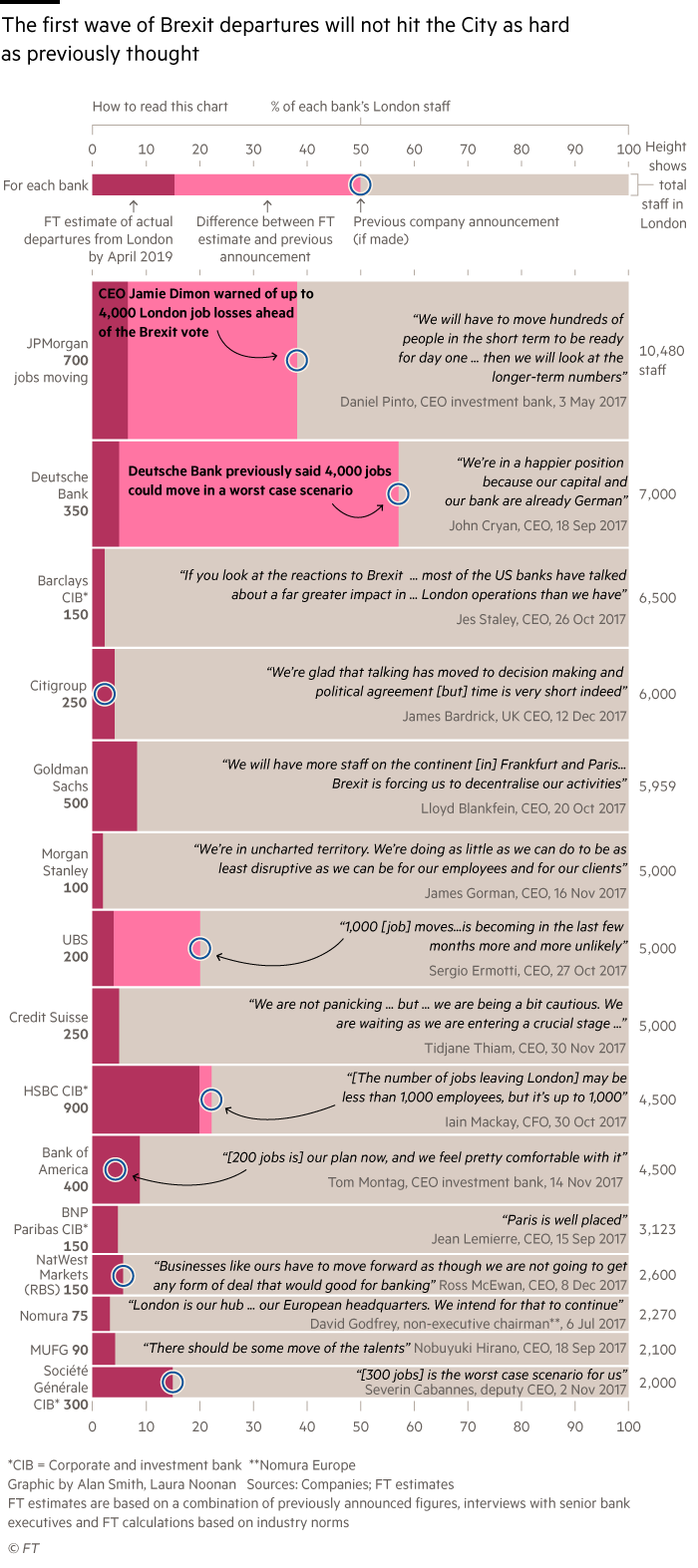

The UK’s biggest international banks are set to move fewer than 4,600 jobs from London in preparation for Brexit — just 6 per cent of their total workforce in the financial centre — according to Financial Times research.

The FT analysis contrasts with consultants’ original claims that tens of thousands of jobs could move from London after Brexit. An EY study this week claimed 10,500 could leave on “day one”.

The FT estimates are based on public statements by 15 of the UK’s biggest international institutions, interviews of more than a dozen senior bank executives about Brexit planning and industry benchmarks.

In the case of Deutsche Bank, where Sylvie Matherat, head of regulation, publicly said up to 4,000 jobs could move, the FT estimates that just 350 jobs may leave by April 2019. The figure amounts to 5 per cent of Deutsche’s London headcount, a proportion broadly in line with other big banks.

Some bankers say the lower estimates emerged as they thought through how many jobs and operations would need to move to the EU if the UK loses access to the bloc’s single market.

“Every city wants thousands of people, but what are they going to do?” said one senior executive at a large US institution, adding that the thousands of people sitting in his London office “cover clients” who will mostly be remaining in the UK.

At JPMorgan, where chief executive Jamie Dimon warned before the Brexit vote of up to 4,000 London job losses, the number leaving before April 2019 is set to be closer to 700.

Goldman Sachs, which has taken a new office in Frankfurt that could accommodate 1,000 people, expects to move fewer than 500 from London. HSBC is still planning to move “up to 1000 people”, although its chief financial officer recently said the figure could fall.

A few banks still do not know how many staff they will move. BNP Paribas, for example, says it is "too soon to speculate" on the potential reduction in its London workforce.

The UK government says it has made important recent progress on Brexit, highlighting last week’s divorce deal with the EU, which paves the way to negotiations on future ties with the bloc and a transition of about two years under current rules — keenly sought by the City.

But Sally Dewar, international head of regulatory affairs at JPMorgan, said her bank’s planning “hasn’t changed to reflect anything that would look like a better [Brexit] outcome”.

A senior executive at another US bank said that a “a watertight transition period that is legally robust” was “the only way we can responsibly stop, or adjust the timing of, the implementation of our plans to ensure post-March 2019 continuation of critical services to our clients, and that needs to happen very quickly”.

Some bankers say the real impact of leaving the EU could still be dramatic. “The story has always been three to five years out, not what does it do to the City the morning after Brexit,” said Rob Rooney, chief executive of Morgan Stanley International. “If people judge it by the numbers that move ([immediately] afterwards, they will miss the point.”

Several banks say they are planning to move relatively few people in the immediate aftermath of Brexit because it will take time for their EU operations to build up. They expect to have very small balance sheets when the EU entities begin handling client business on April 1, 2019, and to be able to run some of the risk and support functions for those small EU entities from London.

David Davis, Britain’s Brexit secretary, says the UK is aiming at a trade deal that includes financial services. If there is a hard Brexit that impedes financial services providers’ access to Europe, one bank’s Emea chief executive said it was “inevitable” that the flow of business from the UK to the EU “continues and continues and that the ECB when they feel the moment is right will push to have much more market risk to be run onshore”.

“It’s a real game changer . . . it will make this day one seem very small,” he added. “If we move the substance of the trading to the continent, you’re then moving risk management, product controllers, compliance legal heads . . . the numbers race to a completely different place.”

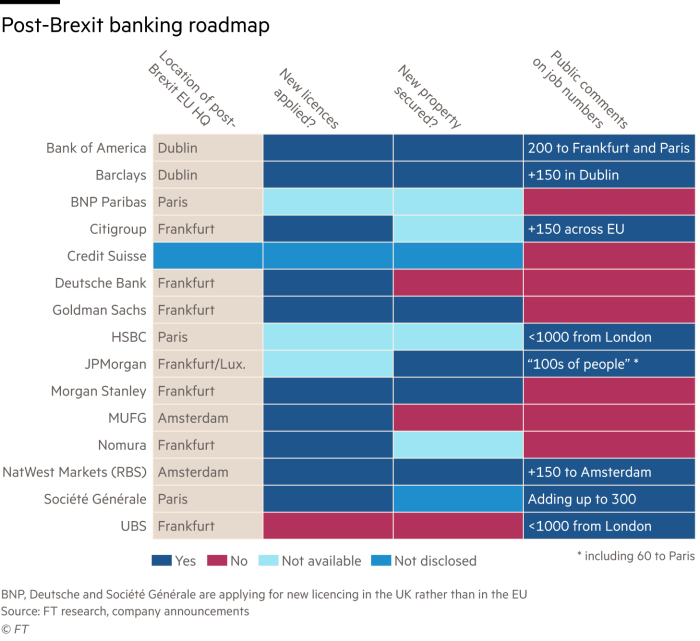

At present, banks are continuing the preparations for a ‘phase one’, the structure they will have in place immediately after Brexit. “We’re already in the process of revamping our governance of legal entities, submitting all of our documents to regulators, identifying senior managers who would have to relocate,” said Ms Dewar.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch has already announced the management of its new EU entity in Dublin — to be led by Bruce Thompson, former group chief financial officer, and chaired by Anne Finucane, a senior executive. Other banks are expected to unveil their EU leadership soon.

While many banks no longer see the first quarter of 2018 as the point of no return, they will accelerate some aspects of preparation. “By the end of [the first quarter of next year] we will start to have to take decisions around informing clients which then becomes more difficult to unravel,” said Ms Dewar.

From around April, banks will begin engaging with clients and “repapering” them to new EU entities where appropriate. Some banks are planning to move existing client positions to new EU entities from the middle of next year.

Bankers stress that how they move business will depend largely on their clients — how they structure their own international operations after Brexit and where they want to do business. Many banks are in the dark on what their clients are planning.

One senior banker said his expectation was that “stuff will go to New York, more will go to the EU, the UK has always been the loser in this, it’s just a matter of how much”.

Comments