Delivery workers feel the heat of climate change

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Larry McBride, a 46-year-old UPS delivery driver in Arizona, was seven minutes away from the regional depot when he pulled over and threw up. Fearing he could lose his job for “theft of time”, he kept on working. Later that day, he was hospitalised for heatstroke and severe kidney injury. Temperatures that day in May last year reached an unusually hot 40C.

A few weeks later, 24-year-old UPS driver Esteban Chavez died on his route in California from sudden cardiac dysfunction. His family blames this on the heat that day, when temperatures peaked at 35C, although UPS noted that the coroner’s report did not mention this as a cause.

The incidents demonstrate how rising temperatures remain a serious concern for all delivery workers, who have the physically demanding tasks of carrying goods and driving vehicles that often lack air conditioning.

These dangers have been underlined by the record-breaking heat experienced worldwide in recent weeks. July is likely to have been the hottest month ever recorded, scientists said last week, with temperatures climbing above 40C across swaths of America, Europe and Asia. And the health risks are clearly demonstrated by a study published in Nature this month that estimated there were 61,700 deaths caused by heat in Europe last summer, itself a record-hot season.

“Worker productivity losses due to extreme heat are eye-popping, but invisible and silent,” says Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center.

In 2021, the centre calculated that extreme heat costs the US $100bn a year in lost labour productivity — a figure that could double by 2030 if no meaningful action is taken. That compares with the estimated $60bn-65bn cost of the record-breaking 2020 Atlantic hurricane season.

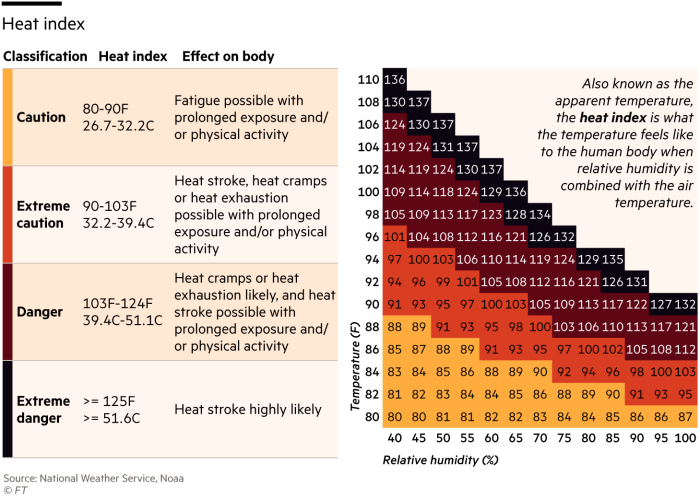

Reasons for this have been closely studied. At 33-34C, a worker operating at moderate intensity loses 50 per cent of their work capacity, according to research published by the International Labour Organization. At high temperatures, which can be compounded by high humidity, people’s bodies struggle to maintain the 37C internal temperature that is essential for normal body function. An analysis by the Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation said that losses from extreme heat were “greatest overall” in service industries — particularly among warehousing and logistics workers, due to limited air conditioning.

At the three biggest package delivery companies in the US — UPS, United States Postal Service and FedEx — 317 workers were hospitalised from heat exposure between 2015 and 2022, which is 16 per cent of the total for such injuries among all US employers, according to FT analysis of Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) data.

However, this is likely to be an underestimate given heat injuries are often under-reported or misclassified — heat can cause someone to fall from a ladder, but the incident may not be logged as heat-related.

UPS delivery vans do not have air conditioning, although the company last week reached a deal with the Teamsters union for this to be provided in new vehicles purchased from January. The deal — which UPS said was a “win-win-win agreement” — covers other issues including pay and is subject to a vote by union members. “The contract fight is about setting an industry standard — this is a critical moment,” says Kara Deniz, a spokesperson for the Teamsters union, which represents 340,000 UPS workers.

The US Postal Service said in December that it would replace its vehicles with air-conditioned models. This is standard in FedEx’s company-owned vehicles, although a significant proportion of its fleet is owned and operated by third parties.

Zakk Flash, an Oklahoma-based package deliverer who joined UPS five years ago, suggests that concerns remain, though: “The message you get from both management and internally is ‘push through it, and you’ll be fine.’ But we have underlying health issues. I’ve got an autoimmune disease. Those things do not go away when we enter the company gates.”

A UPS spokesperson says: “The health and safety of our employees is our highest priority. We instituted new steps to ensure safety and comfort for employees during heatwaves, including providing heat-related gear. We instruct drivers and their management to immediately call emergency services if there are heat stroke symptoms.”

Referring to the McBride incident, UPS said that it “doesn’t reflect the way we train our teams today to respond to signs of potential heat-related illness”. Regarding the death of Chavez, it said: “We are saddened by the death of Esteban Chavez and send our deepest condolences to the Chavez family . . . While the coroner’s report doesn’t point to heat as a cause, and CalOSHA conducted an investigation that did not cite the company, we have been steadily building on our efforts to protect our people in the face of increasingly hot temperatures.”

Baughman MacLeod believes low-cost measures — such as use of fans, water breaks, adapting hours of work and changing dress code — can make a difference. “No one needs to die from extreme heat,” she argues. “We know exactly what to do.”

National and regional governments have started to take action. On Friday, following the latest waves of extreme heat, US President Joe Biden instructed the Department of Labor to ramp up enforcement on workplace heat hazards — for example, by increasing inspections.

Some jurisdictions already have regulations in place governing heat at work. They include California, Qatar and Spain.

Elissavet Bargianni, the chief heat officer of Athens — the Greek capital is the first European city to create the role — says “public and private bodies need to align and specify special measures according to the nature of the work done and working environment”. For example, this month, for the first time, Greece banned construction and delivery work during the hottest hours of the day.

However, even when laws are in place, there is also the challenge of educating employers to identify signs of heat stress, and to enforce safety measures on behalf of workers. Deniz stressed the need for protections to be included in job contracts.

Elizabeth Humphrys, an economist at the University of Technology Sydney who researches occupational heat stress, has interviewed warehouse and logistics workers across Australia. She says the most concerning barrier to workplace heat safety was in workers feeling “incapable or not powerful enough” to take a break.

“Many people can’t take the basic actions necessary to mitigate the impacts of heat stress, such as rehydrating,” she says. Some workers explained they avoid drinking water frequently, because taking toilet breaks would require them to work harder to compensate for time away. “This is a really distressing balancing act,” says Humphrys.

“Businesses are mostly worried about the bottom line. But what gets lost in that are the workers.”

Comments