Theresa May’s 2017 manifesto bungle holds lessons for today

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. One reason why Conservative MPs are happy to be asked what should go in their manifesto is many of them see it as the party’s last hope of turning around their political position. (Another reason is that changing how the country operates is why they got into politics, but we need not let that one detain us unduly today.)

Are they right? Well, up to a point. Anyone who lived through the 2017 general election will know the extent of damage a manifesto can do to a governing party. Theresa May’s manifesto plans to tackle the social care crisis and their subsequent unravelling hurt her very badly and contributed to why she lost her majority. And Jeremy Corbyn’s manifesto also helped drive some of the surge to the Labour party.

But for governing parties, I think manifestos are usually a secondary issue: they can scare voters off, but they can’t really win them over. I was reading the Conservative party’s 1997 manifesto the other day, because that’s the kind of hoopy frood I am. It’s not a document lacking in ideas. Some of the policies (on schools, for instance) have noticeable echoes in New Labour’s own programme in later years, and others (changing rules on adoption, say) ended up being implemented by David Cameron. The Conservative party lost because of other reasons: the charisma of Tony Blair, Black Wednesday, the constant infighting and sleaze, you name it.

The Tory party’s big problems now cannot be magicked away by having some snazzy promises in their next manifesto. But its manifesto could make things worse — and might be helped if Labour’s offering contains howlers of its own.

So we’ll be going through some of what can go wrong with manifestos during this recess. For today, some thoughts about what went wrong for Theresa May in 2017 and why it happened.

Inside Politics is edited by Georgina Quach. Read the previous edition of the newsletter here. Please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to insidepolitics@ft.com

Blueprints

The biggest problem with the Conservative 2017 manifesto is that it was primarily a document about an internal argument in the Tory party rather than a document designed to, you know, win votes.

Theresa May’s election campaign had a theory, namely that:

a) She had inherited a series of promises on tax and spend from David Cameron that could not possibly be kept and she needed shot of them.

b) The majority she had inherited was too small to deliver Brexit.

c) Any election in which the Labour party was led by Jeremy Corbyn was a massive gimme.

As a result of all that, the most important thing to do in the 2017 campaign was to establish a personal mandate for a lot of tricky and difficult issues, rather than to focus on winning over the country as a whole.

And to be fair to her, subsequent events have shown pretty conclusively that a) and b) were in fact correct! But the problem with this theory is that c) was not true. (Or at least, not true enough. Given that May was still able to form a government after everything, you could argue that c) held up. But that’s an argument for another time.)

The absence of anything to vote for in the manifesto became a major problem. There was not only the headline-grabbing issue — that pledge to fix social care inevitably meant talking about who was going to be out of pocket — but also a number of less eye-catching problems. It included very little on animal rights, which meant that, even though the May government planned to continue on with Cameron-era initiatives such as banning the sale of ivory, the party was still attacked and lost votes because it did not mention the policy in the manifesto.

There’s a useful lesson here for both parties, which is that one of May’s biggest problems was that there wasn’t enough political thinking behind the writing of her manifesto. There was a lot of policy thought but not much political strategy.

Whenever Conservative or Labour MPs tell me about their manifesto process, I rarely hear the names of either Isaac Levido or Morgan McSweeney, the two parties’ respective election strategists. This suggests to me that their processes of readying the document look vulnerable to the same shortcoming that Theresa May’s manifesto suffered from.

Now try this

This week, I mostly listened to Harris Conducts Harris, a delightful recording of the American composer Roy Harris conducting some of his own work, while writing my column.

Top stories today

Payouts to top UK dealmakers total £5bn | A group of 3,000 private equity dealmakers shared an annual carried interest windfall of about £5bn in the 2022 tax year. So-called carried interest — the cut of gains PE investors make on successful deals — has come under increasing scrutiny in the UK after Labour pledged to increase taxation of the incentive fee from 28 per cent to the marginal income tax rate of 45 per cent.

Labour warms to Thatcher | Labour is co-opting the memory of former Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher as an unlikely weapon to help Keir Starmer broaden his electoral appeal and win seats across the Tory heartlands.

We need to talk about Brexit | The latest FT film examines why no political party wants to talk about it, why Brexit remains the elephant in the room for British business and how it could actually work better.

Pendle protest | Twenty councillors and their leader have resigned from the Labour party after accusing its national leadership of bullying, reports ITV.

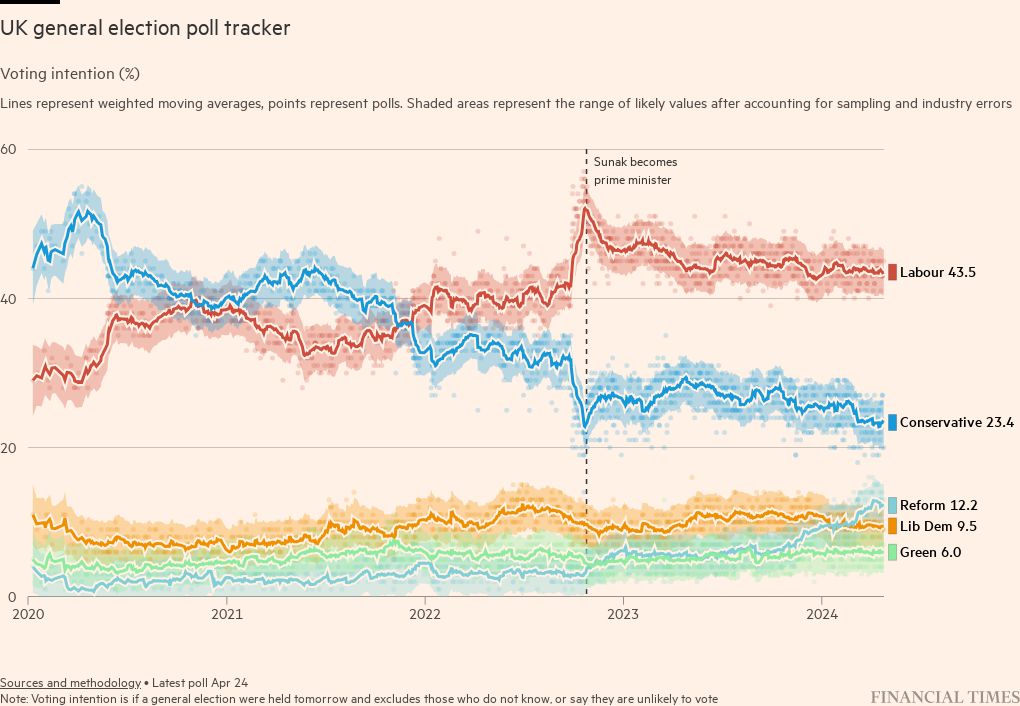

Below is the Financial Times’ live-updating UK poll-of-polls, which combines voting intention surveys published by major British pollsters. Visit the FT poll-tracker page to discover our methodology and explore polling data by demographic including age, gender, region and more.

Comments