A Thom Yorke painting: yours for a song

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The two old friends sitting side by side on a sofa in the basement of a London gallery space are not, as was once rumoured, the same person. One is Thom Yorke, frontman for Radiohead, among the most significant rock bands of the past 30 years. He has shoulder-length brown hair, a greying beard and wears black Comme des Garçons clothing. In keeping with a reputation for nervy awkwardness, he looks down at his feet as he speaks, then out of the window, before finally making eye contact.

Next to him is the artist Stanley Donwood. The pair met in the late 1980s when they were students doing fine art and English literature at Exeter University. Donwood (a pseudonym: his real name is Dan Rickwood) has worked on Radiohead’s artwork since 1994. Bald and bespectacled, one ear festooned with piratical rings, he looks directly at me when talking.

In the 1990s, there was a wild theory that Donwood was really Yorke’s artistic alter ego, as if the singer had a double life as the Banksy of alternative rock – a notion that prompts a hearty burst of laughter from Yorke. Not so nervy after all. Meanwhile, Donwood looks puzzled. “I don’t think it was deliberate,” the latter says of his past elusiveness. “I got accused of being a paranoid recluse and I don’t know where it came from.”

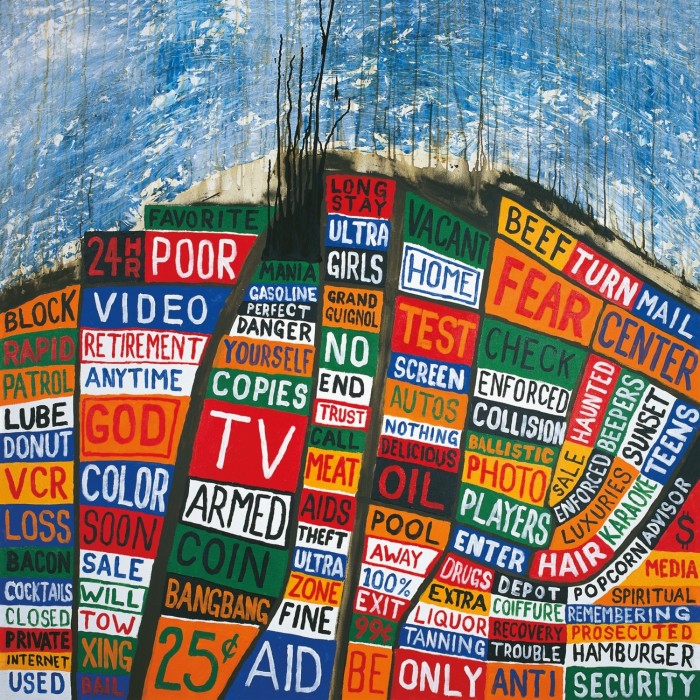

A glance at his work with Yorke might explain. Themes of dread and breakdown recur in Radiohead’s songs, a sense of being lost in a technologically imbalanced world ruled by rapacious bullies. The band’s visual identity is no less vividly disquieting. Childlike cartoons are repurposed to sinister ends, like the band’s logo of a toy bear bristling with teeth. The 2003 album Hail to the Thief has a fold-up map showing city streets riddled with words such as “executioner” and “fear”. Blurry figures loom in a disorienting motorway landscape on the cover of 1997’s OK Computer. Like the feverishly illustrated booklet hidden in the CD case of 2000’s Kid A, nothing is as it seems.

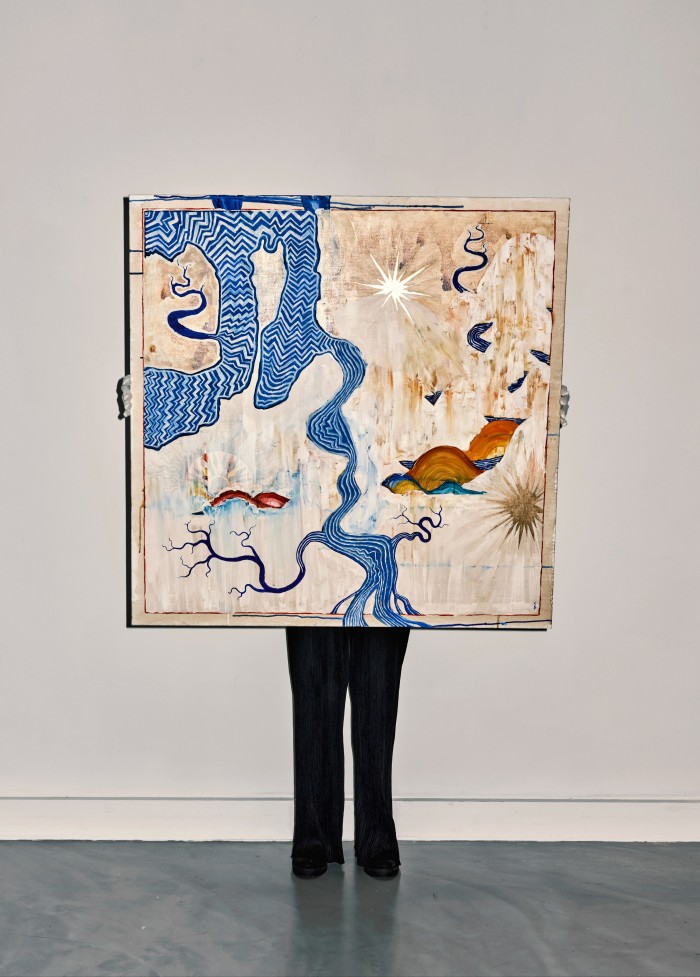

The fruits of the latest artistic collaboration between Donwood and Yorke are propped against the walls of the ground-floor gallery space at Cromwell Place in South Kensington. They’re paintings made for last year’s debut album by Radiohead spin-off group The Smile. Due to be exhibited in a show called The Crow Flies, they depict fantastical bird’s eye topographies of imagined landscapes. With their opalescent-blue river systems and psychedelic hills, the canvases are brighter and cheerier than the duo’s usual work. One of the inspirations was a cartographic exhibition at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, Yorke’s home city.

OK Disruptor: Donwood’s Radiohead album covers through the years

“When I first started thinking about art as a kid, my father had lots of books about nuclear physics whose diagrams I always really liked,” the singer says. (His father was a nuclear physicist.) “I got in a lot of trouble at art school for doing diagrams as paintings rather than natural scenes. So I have an affinity for maps. They’re beautiful by accident.”

The exhibition is organised by the contemporary art gallery Tin Man Art. Following an auction of the pair’s work at Christie’s in 2021, it marks the next step in their tentative emergence as an artworld entity. “I’m not a commercial artist. I think Dan is,” Yorke says, using Donwood’s real name. “My gig is elsewhere. We get together in the context of making artwork for records and paraphernalia around it. I’ve always hidden behind that context. It was kind of a tasty cop‑out for it to be in the context of musical material. So I could say to myself, ‘I don’t have to think of this as a valid piece of work.’”

“We’re making wrapping paper for discs,” Donwood says pithily, unwilling to take the proper-art talk too far. He has had solo shows, published books and worked with authors such as nature writer Robert Macfarlane. He also does Glastonbury festival’s official artwork.

The paintings for The Smile’s A Light for Attracting Attention were done in Yorke’s garden shed at the Oxford home where he lives with his wife, the Italian actress Dajana Roncione. Donwood would get the train from Brighton and cycle over on his fold-up bike. They took it in turns to wield the paintbrush.

“I tend towards a neurotic perfectionism and I hate it,” Donwood says. “I fight against it all the time, which is really difficult when it’s just me.” Meanwhile, contrary to his tortured-artist caricature, Yorke has no such hang-ups. “He’s explosively expressive,” Donwood says. “Dan leads and I follow,” says the singer. “I’m sort of the disruptor.”

They are both 54, born three weeks apart in 1968. They recall the start of their friendship in Exeter. “I was mouthy,” Yorke recalls of his student self. “Well-read, bookish, diplomatic,” is Donwood’s modest assessment of his own youthful character. Yorke admired the sartorial cut of the other’s jib: Donwood had an unstudenty wardrobe of suits and hats.

Originally from Essex, Donwood always wanted to do art. Yorke came to it sideways. “I wanted to do music but couldn’t read it,” he says. “Art school seemed like the next best thing. There were quite a few musicians who I admired who went to art school.” The literature part of the joint degree was a compromise. “English was a way to keep my parents happy, I guess,” Yorke says. “I found that really hard. By the time I’d finished English literature I didn’t want to read a book again for years. Because I found that level of analysis really…” He makes a sound like something deflating and seems to shrink into the sofa.

He writes songs in a free-associative way. “I can’t tell linear stories in lyrics, I find that basically impossible… I’ll often either dream something or, while we’re working on a song, I have a strong image in my head that ends up in the lyrics.” He likes dropping everyday phrases in, a practice inspired by the artist Barbara Kruger. “Maybe the most obvious example is ‘Karma Police’,” he says referring to the single from Radiohead’s magnum opus, OK Computer, whose closing refrain he recites in a conversational tone. “‘Phew, for a minute there I lost myself.’ I probably heard it on a TV show.”

When sung in his trembling high voice, this unexceptional phrase becomes charged with power. “It’s so ironic that for years people would write about the way I wrote lyrics as if it’s like some deep heartfelt thing,” Yorke says. “It’s fucking not at all. It’s like collage. It’s just walking down the street and experiencing something and thinking, ‘What would that be like if I stuck that in your face?’”

The first Radiohead record that Donwood worked on was My Iron Lung, released in 1994. This came as the vinyl era was drawing to a close, to be replaced by CDs. “The record shop was my introduction to art. I didn’t go to galleries,” Donwood says. His favourite record cover is a recondite choice, Throbbing Gristle’s album 20 Jazz Funk Greats. Yorke’s is the floppy disc-mimicking cover for New Order’s single “Blue Monday”, reputed to be so expensive to make that it lost money for each copy sold.

FT Weekend Festival

FT Weekend Festival returns on Saturday September 2 at Kenwood House Gardens, London. Book your tickets to enjoy a day of debates, tastings, Q&As and more . . . Speakers include Greg James, Ludo Hunter-Tilney, Ian Gittins and many others, plus all your favourite FT writers and editors. Register now at ft.com/festival.

Their working partnership took shape at a fertile time for art-music crossovers. The interrelated rise of Britpop and Britart took place in the mid-1990s, a swinging-London reboot in which artists such as Damien Hirst palled around with bands such as Blur in Soho private members’ clubs. Both Yorke and Donwood look dismayed by the coincidence. “We were running away at high speed,” Yorke says. Radiohead held themselves apart from Britpop and its laddish swagger. “There was a lot of that going on,” Yorke says with asperity. “A lot of cocaine and a lot of sarcasm. A lot of ‘I’m much fucking cleverer than you’. For myself particularly, an anxious, prone-to-paranoia person, this was just shit I could not deal with. So I just stayed away from it all.”

Another art-music crossover meets a different reaction. The KLF were the pop duo-turned-art anarchists who notoriously torched £1mn in a filmed ceremony in 1994. Donwood makes appreciative sounds while Yorke mimes bowing-down signs. “We would definitely pin our tail on that donkey,” he says.

This raises the question of their own attitude to the art market. “I’d draw the line at a Russian oligarch,” Yorke says when asked if there’s anyone he’d rather not buy one of his paintings, which are priced from £10,000. “No, apparently I wouldn’t draw the line at a Russian oligarch,” he adds amusedly as Tin Man Art’s gallerist makes frantic signals from across the room.

In contrast, Donwood looks a little pained. “It’s good to sell them but also bad because they’re like your kids, these paintings,” he says. Yorke turns to him: “You realise you’re doing a really good pitch now, right?”

The Crow Flies: Part One, 6-10 September; Part Two, 6-10 December; both at Tin Man Art gallery, Cromwell Place, London SW7

Comments