Carbon bulls will not wait on the EU

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It’s unusual to find an asset class where almost every trader and analyst active in the sector agrees the price is set to rise. But that is the case in Europe’s carbon market, where analysts are projecting the price could more than double in the coming years.

The importance of these forecasts, if they prove to be correct, is hard to understate. The EU’s plans to cut emissions sharply by 2030 hinge, in large part, on the price of polluting becoming high enough for the power sector and industries from manufacturing to shipping to clean up their act.

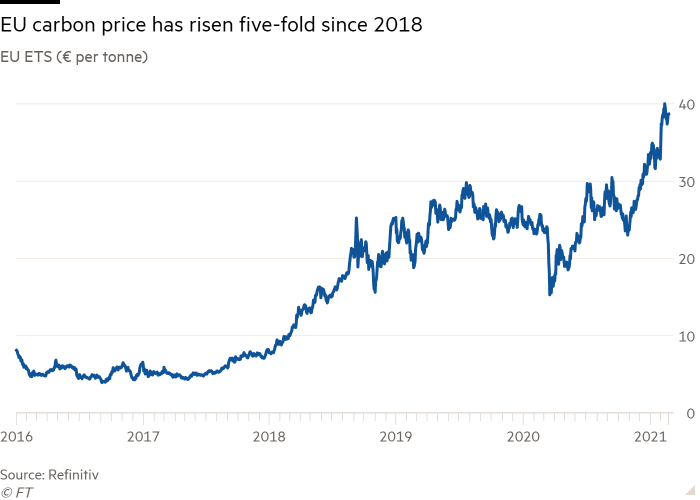

Companies that emit CO2 in excess of the carbon allowances they are assigned need to buy extra in the market, while those that use less — by switching to cleaner fuels or becoming more efficient — are free to sell them. So expectations the EU will tighten supplies over time mean allowances will rise in value. Already, an overhaul of the power sector is well under way, with the rise in the price of carbon allowances — known as the EU Emissions Trading System — rising from less than €8 a tonne of CO2 in early 2018 to close to €40 a tonne today.

That has made it more profitable to burn less-polluting fuels, like natural gas over coal, while giving a significant leg-up to renewables and nuclear power.

But the next target is industry and the sectors of the economy that are harder to switch to cleaner sources of electricity. To make lower-carbon alternatives such as hydrogen competitive in manufacturing the price of carbon is going to have to rise much further.

The important point to understand here is that Europe’s ETS is ultimately a politically constructed market, with the EU controlling almost all the levers.

Having strengthened the EU’s emission reduction targets late last year — to a drop of 55 per cent from 1990 levels by 2030, from 40 per cent previously — the expectation is that the number of allowances will be tightened until the carbon price matches the aims.

When politicians can influence how many carbon allowances should be released — or not — over the coming years, it is not surprising that many in the sector now believe that carbon is undergoing a fundamental repricing.

That is already attracting interest from traders outside the sector. Hard-headed oil dealers such as Vitol are getting into the space. Pierre Andurand, whose hedge fund has made a fortune betting on swings in the oil price, has started to make bullish bets on carbon.

But the rally since late last year is starting to cause some disquiet, not least among carbon specialists unaccustomed to the rush of interest in this once-sleepy market.

Marcus Ferdinand at ICIS, a consultancy, sees the price reaching €80 a tonne by 2030, but he worries the pace of the gains has been too rapid.

“The market is on speculative steroids for the moment,” he said. “Long term, there is a reason for the price to move upwards and to be sustained — but the speed it is happening is too high.”

Ferdinand is right, to an extent, to be concerned. A soaring carbon price quickly has real-world implications. The desire to decarbonise industry in the coming years, which for now enjoys broad-based support, can quickly get politically messy if carbon-intensive businesses complain they are being squeezed faster than they can adapt.

At some point, the EU might seek to intervene if it judges that the price has gone too far, too fast.

But it is not clear restricting trading would be the best solution. If the EU’s long-term goal is a higher price then it cannot blame investors for looking to buy now, when prices are still relatively low.

That is a failure to understand how markets work. To draw one parallel, the oil market did not rally between 2003 and 2008 because there was an immediate shortage of oil — but because of expectations that there would not be enough in the future. The carbon market is in a similar place today.

Ingvild Sorhus, lead EU carbon analyst at Refinitiv, believes the price will be just under €90 a tonne by 2030. She said that businesses and the EU needed to prepare now.

“At some point you need to see carbon prices go up substantially,” she said. “To survive in the long run, you need to think of how you configure your business to survive in a low-carbon economy.”

Policymakers and businesses should take note. If the EU is serious about higher carbon prices, it will also need to think more quickly about measures to mitigate the effect on its own industries.

If the path to higher prices has been set, it can’t expect the market to wait until it’s ready.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here

Comments