The overlooked genius behind the Black is Beautiful campaign

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I became fascinated by Emmett McBain when I discovered the Black Marlboro Man. When most of us think about retro Marlboro advertising, we see the iconic white cowboy, squinting at the camera in his red shirt. That image was replaced for me by one of a black man in orange and tan standing on the street with a woman in a dotted head wrap, and another of the same man buying fruit from a market.

The Black Marlboro Man was not a narrow-eyed, masculine trope but a relatable, everyday man for African Americans of the time. Putting aside the questionable ethics of selling tobacco, the advert opened a door to a history of black advertising that felt authentic and respectful. The advert, made under the umbrella of Burrell-McBain Inc (“An Advertising Agency for the Black Commercial Market”) formed in 1971, was a partnership between Tom Burrell, who was a copywriter by trade, and McBain, who was a graphic designer.

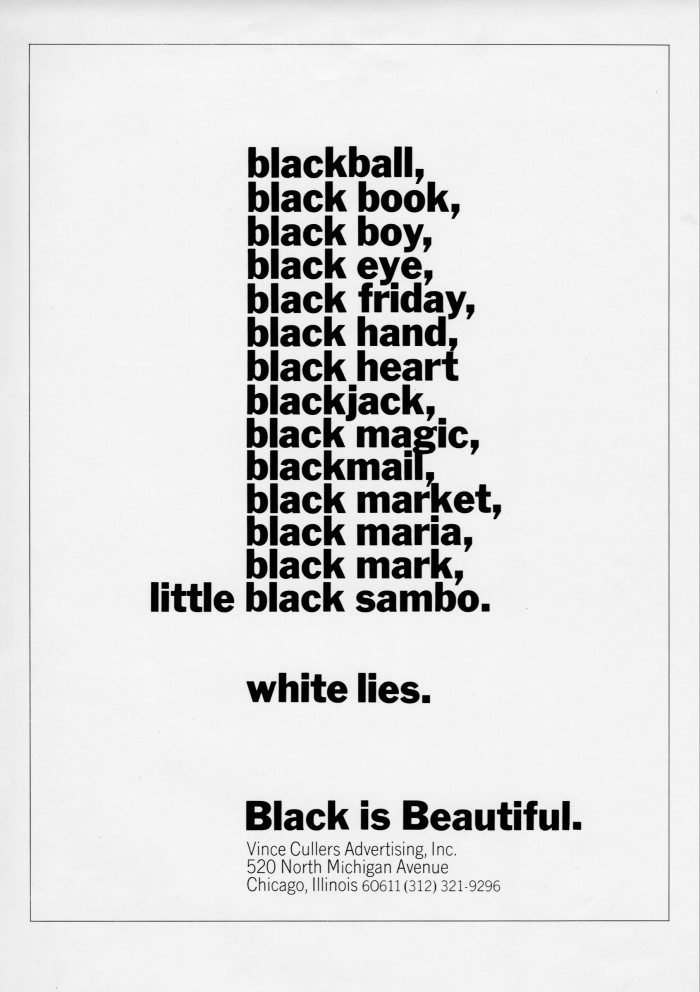

Burrell understood that “black people are not dark-skinned white people”, and McBain’s work spoke to that intelligence with a portfolio that includes the iconic “Black is Beautiful” advert – a monochrome masterclass on insidious racism – that he made in 1968 in his position as creative director at Vince Cullers Group. The agency, founded in 1956, was the first African-American full-service advertising agency.

Born in Chicago in 1935, McBain began taking weekend classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago when he was 12. Seven years later, he enrolled at the Ray-Vogue Art School, and eventually graduated from the American Academy of Art in 1956 before starting work at Vince Cullers Group. Very quickly, he moved to Playboy Records as an assistant art director at the age of 22, and within a year was promoted to art director. Here, he created a body of album covers for artists including Tony Martin, Max Roach and Sarah Vaughan, winning Billboard’s Album Cover of the Week for his design for The Playboy Jazz All-Stars.

McBain’s album sleeve cover for Travelin’, 1960, by John Lee Hooker

Vaughan and Violins, 1959, by Sarah Vaughan

More album covers were to follow when he set up his own design studio, McBain Associates, in 1959 and worked with Mercury Records, designing more than 75 album covers by the time he was 24. But it was in 1968, after returning from an extensive European and African trip, and prompted in part by fatigue with the continued racism and persecution of black people in the US, that McBain threw himself into black Chicago’s cultural revolution and rejoined Vince Cullers to make the seminal “Black is Beautiful” advert. In 1971 he opened Burrell-McBain, designing for everyone from Marlboro to McDonald’s to Coca-Cola, in the process becoming the country’s largest black-owned agency. Where their work stood out was how it depicted black people as normal and beautiful rather than exoticised. One of my personal favourites is a father and son eating their burgers in a McDonald’s advert with the copy reading “Daddy and Junior Gettin’ Down”.

A number of factors contributed to their success at the time, but an important change taking place was that big manufacturers were realising the value of the black market. Prior to the 1960s, advertising to African Americans mostly took place in black newspapers, and white clients saw black consumers as having little disposable income, as well as being dangerous by association within the politically charged climate. The realisation that African Americans were spending nearly $30bn a year brought in a new era of pragmatism as clients tried to tap into the market.

It’s that same pragmatism mixed with hints of social purpose and cultural relevance that drives the advertising world to speak to and include a black audience in the campaigns it now makes. Black spending power in the US was estimated at $835bn by McKinsey in 2019, and the Black Pound Report in 2022 found that the disposable income of the multi-ethnic consumer was £4.5bn. Money aside, the cultural value of blackness is immeasurable when you assess the impact made across music, fashion, film and literature, among other things. What I found particularly interesting about McBain’s work was how sensitive it was to the black experience when current advertising – either featuring or speaking to black people – still struggles to hit the right note.

The Magic of Sarah Vaughan, 1959

Playboy Jazz All-Stars, 1956

Black marketing can be a perilous space to enter. The now-notorious Pepsi commercial featuring Kendall Jenner drew inspiration from the story of Ieshia Evans, a black woman who was one of 102 protesters arrested in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in July 2016, where she was protesting the shootings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile by police. The Pepsi ad seemingly references this incident and the famous “Tank Man” photo from the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 with a cohort of young, attractive Gen Zers. The film climaxes when Jenner moves toward a line of policemen and offers one a can of Pepsi. Most criticism pointed to the thoughtless co-opting of the BLM movement.

On the other end of the spectrum, Colin Kaepernick’s commercial for Nike the following year inflamed opinion. People from the “white lives matter” brigade threatened to boycott Nike, but the commercial won a creative Emmy and fellow sports stars Serena Williams and LeBron James offered their support. Whatever your thoughts may be on Nike as a corporate entity, it took a risk by aligning itself with a sportsman who had become persona non grata in his league.

There are other references to consider when marketing to a black audience. Procter & Gamble’s campaign “My Black Is Beautiful” was originally started by black women at Procter & Gamble in 2006 with a remit that it “empowers, celebrates and ignites meaningful dialogue and change around the topic of bias and the ever-evolving subject of beauty, as well as its influence on culture”. To date, one of its most effective campaigns has been “The Talk”, where black parents have to explain to their children some of the prejudices they will face in life because of their skin colour. In one commercial, a mother explains to her daughter that she is “not pretty ‘for a black girl’. You are beautiful, period.”

It’s a good time to reflect on the work of Emmet McBain. Ultimately, he quit the advertising game and opened art gallery and consultancy The Black Eye, which focused on design for nonprofits and publishing houses. He organised a series of nationwide arts programmes, community projects and scholarships promoting African‑American voices, funded by Beefeater gin. Where brands today still stumble with clumsy representation and misplaced cultural appropriation of negative black stereotypes, McBain focused on the very normal, very beautiful, everyday experience of blackness in a way that spoke to and about black people without othering.

Now You See Me: An Introduction to 100 Years of Black Design by Charlene Prempeh is published by Prestel at £24.99

Comments