Ebola’s worst enemy: disease control expert Dr Anthony S Fauci

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Dr Anthony S Fauci swings open the front door of his 1927, stucco house in northwest Washington DC on to a bright winter’s day. As director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (one of the US National Institutes of Heath), he oversees an annual budget of $4.5bn. From this powerful perch, Fauci — who once sparred with Aids activists before becoming their top federal research advocate — is now helping battle against another devastating disease: Ebola.

In two weeks’ time, Fauci, 74, will head to Liberia for the world’s first large-scale clinical trials of Ebola vaccines. “We’re testing two out of three [potential vaccines] on 27,000 people,” he says. “We’re testing our NIH vaccine, developed with Glaxo[SmithKline], and we’re testing the Canadian NewLink-Merck vaccine.” A third vaccine, from Johnson & Johnson and Bavarian Nordic, is in the pipeline. “The British are doing phase-one trials,” says Fauci.

As the Ebola crisis unfolds, Fauci, with his direct manner, is once again a familiar presence on television screens, updating a jittery public. “I’ve been doing that for many years,” he says. “I did that in the panic of the anthrax attacks. I did it with the early years of Aids, Sars, swine flu.” He celebrated the recovery of Nina Pham, a nurse who contracted Ebola last year, with a widely broadcasted embrace. “My hugging her was to show it was perfectly safe to hug a recovered patient.”

On the stairway of his home are school photographs of Fauci’s grown-up daughters, Jennifer, Megan and Alison, a Stanford graduate who works at Twitter. Does Fauci tweet? “I sleep four, maybe five hours a night and I don’t have time to tweet.” Yet, it was Nina Pham, from her hospital isolation pod, who urged him to learn to make video calls on his iPhone. “We had to get in and out of these bulky suits to check on her . . . As she was recovering, she said, ‘Why not use FaceTime?’”

Hanging by the front door is a print of the Brooklyn Bridge. “It reminds me of where I grew up,” says Fauci, a second-generation Italian. “My parents were from the Lower East Side. Moving to Brooklyn was moving up.” As a student in high school, Fauci played basketball “in a tough league with very good people”. Did playing sport prepare him for life in Washington? He smiles. “It taught me to organise my time.”

After enrolling at Holy Cross college, Massachusetts, where he mixed science with classics, Fauci went on to study medicine at the Cornell medical school and began research on immune-mediated diseases. “I found some cures for fatal immune-mediated diseases . . . But in 1981, when the first cases of what turned out to be Aids appeared, I made a dramatic turn in my career,” says Fauci, who assumed his current post in 1984. “I studied Aids.”

Fauci bought his home as a bachelor. “I’ve been living in this house since 1977. I bought it when it was an old broken-down house and I’ve done four renovations,” he says, leading the way into a bright sitting room with floor-to-ceiling windows. “When I got married, in 1985, I renovated the attic to make an office for my wife. When we had our first child, we renovated the bedrooms.”

His wife of 29 years, Christine Grady, is a trained nurse and chairman of the department of bioethics at NIH. “She was a triple threat,” says Fauci, with evident pride. “She went to school to get her PhD in philosophy, worked, and had three children . . . We met over the bed of a patient.” He throws open the back doors that lead to a broad wooden deck he installed and points enthusiastically to the tall trees that circle the property. “I bought this mostly for the backyard and the hundreds-of-years-old trees,” he says. “I was raised on the streets of Brooklyn, so I love the space.”

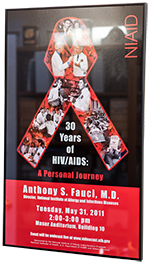

On the wall of his corner office is a poster for a conference on Aids. Fauci describes his relationship with the more militant Aids activists such as the playwright Larry Kramer as “complex”. “They disrupted Wall Street, they went into St Patrick’s Cathedral, tried to grab the Eucharist,” he says. Fauci finally met with the protesters against opposition from his staff. “I opened the door to letting the activists in . . . They were aggressive but they were right.” Today, he counts Kramer as a close friend.

The emergence of Aids prompted Fauci to focus on HIV research, which has led to numerous awards. He was an architect of the Bush administration’s PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for Aids Relief) and is now optimistic about a vaccine. “It’s one of the most difficult scientific endeavours because it is hard for the body to make an adequate immunological response,” he says, “[but] I think we will get there.”

Favourite thing

“Maybe my favourite thing is the back deck,” says Fauci. “It’s the bridge between the middle of the city and the middle of nowhere.”

He is also fond of a plant at the office. “I brought it into my office when I first started in November 1984. It’s grown these high tentacles. I had to get bungee cords to keep the thing up. It’s 30 years old and still alive and growing.”

Wedged above a shelf piled with biographies and thrillers is a photograph of Fauci with Dick Cheney, the then US vice-president. “It’s after the anthrax attack when he put me in charge of preparing for biological threats,” he says, “I convinced him that the greatest terrorist was nature itself.” The NIH Ebola vaccine, he says, was in development for a decade but it took the current crisis for the global public health community to convince drug companies to ramp up production.

Comfortable furniture has been collected by the family over the years. Fauci points to a velvet sofa punctured by scratches. “My daughter brought her dogs home,” he laughs. He pauses by a fine clay bust of a bearded man. “I did that. That’s Ernest Hemingway. I took a little sculpture class they had at Walter Reed hospital.”

He admits he has little time for extra activities these days. In addition to the Liberia trials, a smaller Ebola vaccine trial in Sierra Leone will begin soon. “It’s run by the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention],” says Fauci, who talks to the organisation’s director, Tom Frieden (a fellow New Yorker), every day. “He calls in around 11pm.”

Fauci and Frieden are also both in regular contact with the White House. “The president has been personally involved in every step. He got $5.3bn for Ebola from Congress . . . When he asked what I needed, I requested $238m, and got $238m for the vaccine trials,” says Fauci.

Whose idea was it to send US troops into Liberia to help fight the disease? “It was mine and Tom’s. We argued that we needed the organised command-and-control logistics. Although we had the science, we didn’t have the infrastructure.”

Fauci describes the Ebola outbreak as happening in “the perfect storm. The affected countries were poor, didn’t have infrastructure, and they distrusted authority after the civil wars”. Yet with the dramatic decrease in cases in Liberia, and new clinics pictured without patients, was the military effort worth it? “That’s one of the reasons Ebola in Liberia has gone down so dramatically,” insists Fauci. “Public health measures worked.”

So will the vaccines work? “We hope that by the middle of 2015 we’ll know. Either they work or, if the infections burn themselves out there, we’ll get important data.”

Photographs: Kate Warren

Comments