VW chief defies sceptics with ambitious plans to overtake Tesla

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Volkswagen unveiled its first battery-powered prototype in 2009, chief executive Martin Winterkorn warned about “electro-hype” — the idea that this new technology could be as affordable and ubiquitous as its fleet of petrol and diesel cars.

A decade later, VW’s incumbent boss Herbert Diess is spending more than €33bn on proving him wrong.

The German group has launched a wildly ambitious plan to produce 26m emission-free vehicles in the next nine years, leapfrogging Tesla to become the world’s largest electric carmaker.

But perhaps the most radical element of the scheme is its focus on generating profits almost from the get-go, in defiance of dire industry-wide projections.

“When it comes to pricing for the next generation . . . [profitability is] on the level of a Golf [VW’s best-selling combustion engine car],” Mr Diess told the Financial Times.

The first car to make Golf-level margins will be a battery-powered model the size of VW’s Tiguan sport utility vehicle released next year, and built on VW’s purpose-designed modular electric skateboard, he added.

This forecast puts the company in pole position, ahead of some of the automotive world’s largest players, including Toyota and General Motors, who caution that their electric cars are years away — perhaps even a decade — from being able to generate petrol-level profits.

“This is a very bold statement,” said one person close to VW’s top investors, upon hearing about Mr Diess’s projection. “It would be a surprise if that was possible.”

McKinsey estimates that midsized electric vehicles cost $12,000 more to produce than their petrol or diesel counterparts, forcing carmakers to charge more or face squeezed margins.

VW’s rivals “face three or four years of pressure on their profit margins” due to electrification, said Jürgen Pieper, a car analyst at Metzler bank.

What sets VW apart, Mr Pieper added, is its “very tough” culture. “I probably wouldn’t like to work there,” he said. “There are hirings and firings all the time, but what I like is the culture of ambition.”

That culture of ambition was in part what led to Dieselgate, the 2015 scandal that saw VW admit to having sold 11m cars worldwide fitted with devices that under-reported emissions of nitrogen oxide.

The fallout is still being felt five years later, with VW on Friday agreeing to an €830m settlement in a lawsuit brought by more than 400,000 affected drivers in Germany.

The scandal also made the company a lightning rod for criticism of the industry from environmental groups and European lawmakers.

Today, Mr Diess admits the company is the “focus” of EU rules that force carmakers to lower CO2 emissions. “We are happy with it,” he said, “because if society decides, ok, we’ll go for electric cars, actually that’s good for us.”

Ever since he ascended to the top floors of VW’s Wolfsburg headquarters in 2018, Mr Diess has been insistent: despite concerns about the lack of consumer demand, inadequate charging infrastructure and bottlenecks in battery supply chains, the company’s decision to bet the farm on electric vehicles is more than a high-risk gamble.

“There is no other alternative to electric cars,” he said, in an office overlooking the sprawling factory halls and railway tracks that criss-cross VW’s historic home.

In a week that saw the production of Audi’s electric e-tron model grind to a halt due to battery supply shortages, Mr Diess added he was confident that the company had identified enough lithium-ion cell supply to see it through to the end of 2023, by which point it hopes to have produced 1m emissions-free vehicles.

But the former BMW executive, who first arrived at VW just a few months before the diesel emissions scandal broke in 2015, wants to do more than just shepherd the company out of its self-created crisis.

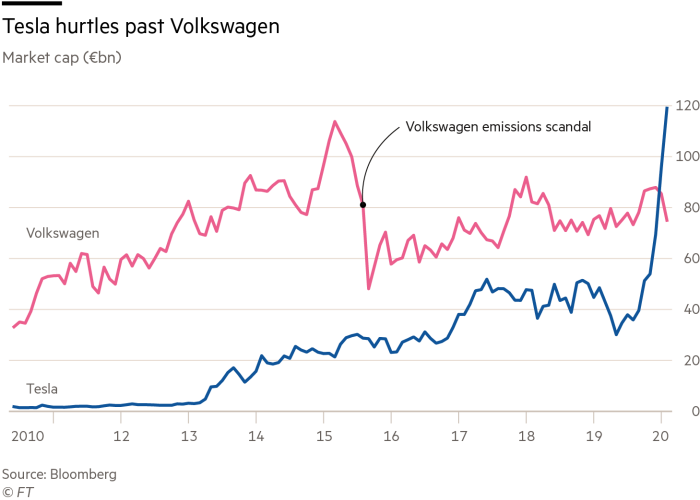

His long-term aim is to convince capital markets to treat VW more like Tesla than an old-world car manufacturer, propelling it to a market value of €200bn, more than double its current €75bn valuation.

Investors are yet to be fully convinced.

VW boasts annual sales of almost 11m and has suffered only two lossmaking years in the past three decades, on Friday reporting a 17 per cent increase in pre-tax profit for 2019, and pledging to vastly increase its dividend.

Yet the company is eclipsed in market value by Tesla, which has sold fewer than 1m vehicles in its 17-year existence, and has yet to post a yearly profit.

Mr Diess, who was on stage at a car industry award ceremony in Berlin when Elon Musk announced Tesla would be building his first European factory a mere 150 miles from VW’s base, has gone out of his way to compliment the Twitter-keen chief executive, crediting him with “paving the way” for electric cars.

“[Mr Musk] is taking risks which we couldn’t,” said Mr Diess. “So I think we make a good pair because he is pulling ahead and we are fast followers, we try to keep as close as possible.”

Despite Mr Diess’ confidence, the odds of achieving this goal appear to be stacked against the German carmaker.

Its unique ownership structure, in which the Porsche and Piech families indirectly own a majority stake, and the state of Lower Saxony has a blocking minority, prevents the company from rushing through seismic shifts in strategy. The strength of the unions on its supervisory board also makes radically reducing VW’s 300,000-strong German workforce almost impossible.

Additionally, while Tesla can raise more than $2bn overnight by issuing new shares, “Mr Diess would have to sell 2.5m cars to get that money,” said a person close to investors.

VW has to rely on debt to finance its overhaul, and has “de facto no equity capital market access”, he said.

“What Diess is doing is braver than what Elon Musk is doing. He needs to fund this transition with 4 per cent profit margins from VW [brand].”

It is, therefore, unsurprising that improving returns is high on the VW chief’s agenda.

Addressing 120 of the company’s managers in Berlin this year, Mr Diess made it clear he would happily halve Bentley’s annual sales in exchange for higher earnings. Returning to profitability in the US, where VW has languished for years, is also a priority.

But the fate of the world’s biggest carmaker, he emphasised, is not merely dependent on boosting margins, but “more about managing the transition [to electric] better than others”.

“If you look at Tesla’s evaluation, it’s not about profitability,” Mr Diess said. “It’s a new game, and that’s also what I have always said.”

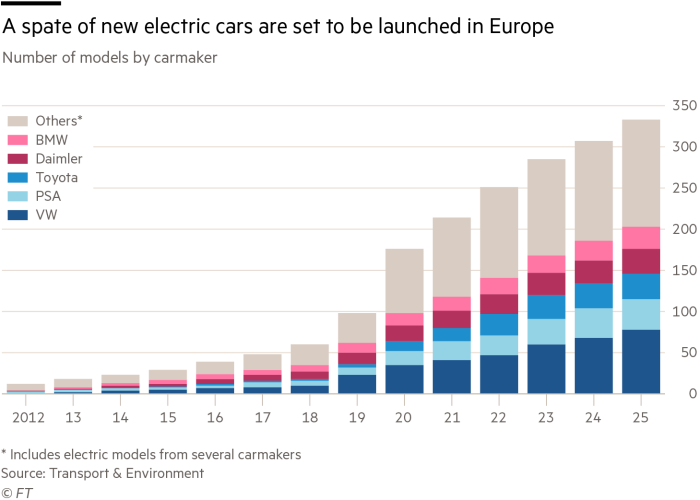

The rules of the game have partially been set in Brussels, which has fuelled the shift to electric vehicles by forcing car manufacturers operating in Europe to lower their fleet-wide CO2 emissions drastically over the next few years, or face billions of euros in fines.

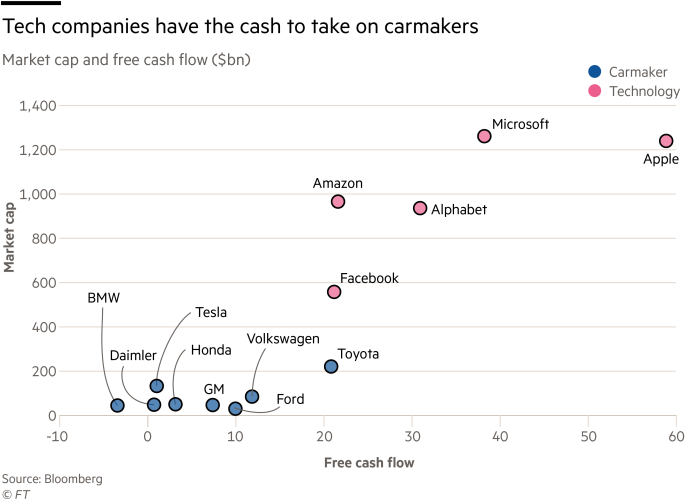

Thousands of miles away, the likes of Google and Uber in the US are threatening to rewrite the carmaker playbook, betting that decades of auto-building expertise can either be aped or acquired.

It is a threat Mr Diess takes seriously. “[Tech companies] have to invest a lot [to become carmakers],” he said. “It’s still scary because they are so rich that they could. If you have 100-and-something billion in cash, you can buy whatever you want. The question is, do they really want to?”

Before waiting to find out the answer, the VW boss is intent on taking the battle to Silicon Valley.

In a country whose postwar economic growth has been driven by hardware excellence, Mr Diess hopes to attract the necessary talent to help VW write the 300m lines of software code that will power electric and semi-autonomous vehicles, as well as battery-management tools and entertainment systems.

“The big differentiator in the future will be software, direct customer contact, the car becoming an internet device,” said the chief executive, who is pouring roughly €8bn into software development in Berlin, Bavaria, the US and China. “This is our biggest effort.”

The effort is focused on the ID. 3, VW’s talismanic electric model, and its first emissions-free mass-market hatchback.

Launched in November to great fanfare by Angela Merkel, Germany’s chancellor, the car, which will be priced at about €30,000 and is due to go on sale in August, will feature a 4G-enabled, centralised software system.

VW needs to sell hundreds of thousands of ID. 3s, and other electric models, to bring down its fleet-wide CO2 emissions and comply with EU regulations. For 2020, every electric car it sells will be counted twice by regulators — in future years the added weight given to them decreases. But its production at VW’s east German Zwickau factory has been plagued by complications over the installation of complex technology inside the car.

Other short-term risks could prove an even bigger hurdle for VW.

Last year’s contraction in the global car market shows little sign of being reversed in 2020, while the impact of the coronavirus on China, its most profitable market, all but wiped out sales in February. The disease, which forced the cancellation of this week’s Geneva Motor Show, has also thrown the industry’s complex supply chains into chaos.

But Mr Diess is adamant that neither the outbreak nor an economic downturn will curb his commitment to electric vehicles.

“There has been a major cultural change at Volkswagen, and it has to do with [wanting to move on from] Dieselgate,” said Metzler’s Mr Pieper.

All the more reason, he said, to consign the strategies and soundbites of Mr Winterkorn, who is facing criminal charges in the US and elsewhere, to the past.

Comments