Ocado delivers on promise of high-tech future

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Smoke billowed into the chilly night from a fire at Ocado’s automated warehouse in Andover, southern England. The blaze, which started in the robot grid, gutted the online grocer’s flagship distribution centre.

Not for the first time in Ocado’s history, investors were spooked. In two days £1bn was wiped from the company’s £7bn market capitalisation. Before the fire in early February, the state-of-the-art Andover depot had handled 10 per cent of the retailer’s capacity.

Yet the blaze failed to spark a sustained sale of Ocado’s shares. Unlike previous bouts of bearish sentiment towards the company — which was once one of the most shorted on the London Stock Exchange — the shares recovered a good deal of their losses in the days following the fire.

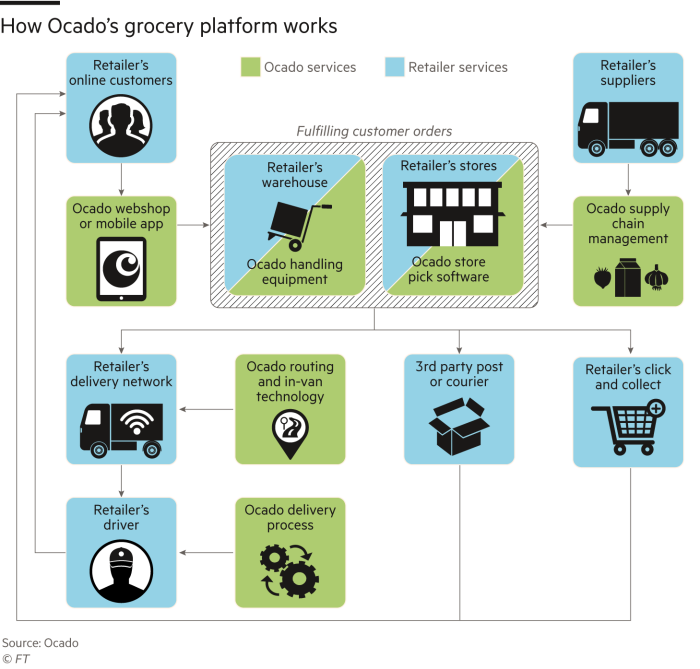

It is Ocado’s bold evolution — from an online grocery delivery service to a technology company with a £1.6bn turnover that builds everything from consumer-facing websites to robot-operated depots for other food retailers — that analysts say has underpinned the group’s new-found market resilience. This evolution has placated many of Ocado’s early critics, who were concerned by what they deemed a high-cost business model with limited growth prospects.

Tim Steiner, a former Goldman Sachs bond trader, co-founded Ocado in 2000, sourcing goods from its trading partner, UK supermarket chain Waitrose.

It was not long after he took Ocado public in 2010 that Steiner encountered market scepticism.

Bearish analysts highlighted the company’s failure to secure further third-party deals following its 2013 tie-up with Wm Morrison, another UK grocer. Yet the management team held its nerve and focused on developing its technology.

The former short-seller’s favourite went on to become the best-performing stock in the FTSE All-Share index in 2018, almost doubling in value during the year on the back of international expansion deals that propelled Ocado into the FTSE 100 index in June.

On the morning of the fire, Steiner was unveiling Ocado’s annual results and gave a nod to the struggle by lauding his company’s “18-year overnight success”.

Just weeks later, this transformation was completed in a deal to spin off Ocado’s legacy UK grocery retail business into a £1.5bn joint venture with rival Marks and Spencer.

Bruno Monteyne, an analyst at broker Bernstein, credits Ocado’s management for its “relentless focus” on creating new technology. “[Management] could have slowed down innovation a few years ago and focused on making the UK a nice cash-generative operation [to] then sell it to Waitrose. Instead, it focused on ongoing innovation,” he says.

It was always part of Ocado’s plan to develop some intellectual property and license it, but management had little idea of how much it would have to create until its technology teams tried to mesh third-party software with the hardware needed to build the infrastructure behind online grocery retailing.

The synthesis did not work well enough. “We started to design the facilities ourselves and write all the software ourselves, and later decided to build our own material-handling solutions and robotics ourselves,” says Steiner.

An important early piece of software acted as a “control layer” over its smart warehouses. This balanced the operations of the building. At points this meant slowing down certain zones and moving human pickers to different stations to ensure the irregularity of grocery orders did not create gridlock. “Eventually we created software that meant we could deal with those oscillations and operate right underneath the maximum capacity of the building,” says Steiner.

The drive for efficiency and the robotics work led ultimately to the Andover warehouse, which opened in 2016, showcasing Ocado’s “hive” automation. More than 1,000 robots use a 3D grid system to move groceries from storage to human pickers. Because the robots can pass each other, the potential for gridlock is avoided.

Ocado has now designed everything on its platform, from the website search engine (ensuring, for example, that a search for “milk” does not return a handwash or a chocolate bar) to the algorithms in its van-routing software.

The close integration of the warehouse software with the front-end consumer website means Ocado can give customers live availability and automatically reorder stock from suppliers. It also has a growing general merchandise business via brands such as Fetch, which delivers pet supplies through the same platform, and plans to trial a one-hour delivery service in London.

The next frontier is robotic picking, which should go live this year but is still some way off dealing with the 50,000-plus products of varied shape, weight and rigidity that the online grocer handles.

When it came to selling the technology, Ocado originally kept its cards close to its chest. “We had a view that we weren’t spending our shareholders’ money to learn about this market to be [a] free university and to teach the rest of the world,” says Steiner.

But a couple of years after the 2010 listing, management decided that showcasing Ocado’s technology would not enable copying. Retailers and bankers watched the innovation in action, and soon UK supermarket chain Wm Morrison signed up for a website-to-doorstep ecommerce service.

The market was keen for more deals, but Steiner says Ocado was not ready to run multiple retailers. It focused on building a solid, replicable platform. In 2015, Ocado tried to sell the platform but struggled initially. “We set out to sell it, had a couple of hiccups along the way, but remained resolute in our beliefs,” says Steiner. “We held steady.”

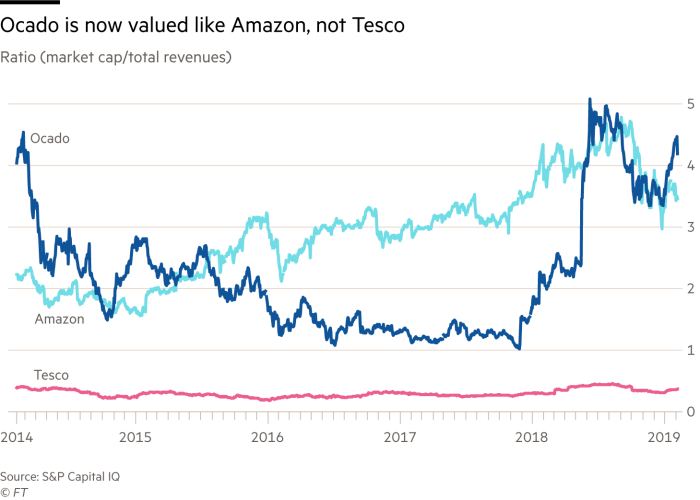

This patience paid off in 2017-18, when Ocado signed up retailers including France’s Casino and Kroger in the US: the latter an agreement in principle to provide 20 automated warehouses. The stock market lauded a turnround. Just prior to the M&S deal, Ocado’s market capitalisation was equivalent to about four times its revenue, reflecting that investors valued it more like a US tech company than a UK grocer. Amazon, the US ecommerce giant, trades on more than three times its own turnover, while Tesco, the UK’s biggest supermarket group, just 0.4 times.

Bernstein analyst Monteyne sees Ocado’s advantage in the website-to-truck breadth of the ecommerce platform. For partners, a two-year window to build a smart warehouse is faster than buying separate components and putting them to work, he adds. This pace of innovation means catching up will not be easy. “Everything can be copied, but even copying takes time,” says Monteyne.

Where stock market analysts once focused on Ocado’s failure to do deals, now many are bullish about how far those deals can go. James Lockyer, an analyst at broker Peel Hunt, believes the technology business has the potential to become the “Microsoft of retail”.

This would require Ocado to move from exclusive licensing of its platform — as with Kroger — to becoming a standard industry platform. “At the moment [Ocado] is exclusive,” says Lockyer. “It is using that exclusivity to gain its deals but, over time, that might reduce its potential.”

But innovation is not free. Capital investment of £170m in the 12 months to December eclipsed operating cash flow of £128m, as it has each year since listing. The company’s balance sheet is healthy, but that is after £333m of proceeds from share issues last year.

Every tie-up increases the investment demand. “It’s a slight irony of our accounts and our cash usage that the more successful we are, the worse our accounts will look in the short term and the more capital we’ll require,” says Steiner. The M&S deal will help: it will give Ocado £750m in cash for a half-share of the joint venture, which, according to the latter’s management, will fund all smart warehouses currently planned.

The more bullish market-watchers see Ocado gaining strength to negotiate deals that are better for its cash flow. “As the deals get stronger, there should be more upfront payments,” says Lockyer at Peel Hunt.

But sentiment could again sour. Ocado must now tackle the challenges of fulfilling its deals with Kroger and Casino. If the company is not bought out, analysts expect the group to demonstrate that these third-party tie-ups have been worth it by generating a decent return on capital. Analysts have been given little information on the terms of the deals to forecast how profitable they will be. Despite rising sales, Ocado reported a £45m annual loss for 2018.

The Andover fire was a big disruption and Ocado-watchers have speculated that the blaze could unsettle the company’s partners.

Brexit also looms. Ocado holds just seven days of inventory by volume, as perishables cannot be stockpiled. “We run our business lean,” says Steiner, adding: “We just have to hope that the government and the governments in Europe keep the ports flowing.”

Grocer partners will come and go, but Ocado says it will keep building. Its patent application count is close to 400. “Our biggest innovation was not to try and have a single innovation,” says Steiner. “Our biggest innovation was to become an innovation house.”

Comments