Why you should ditch ‘follow your passion’ careers advice

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Work is supposed to bring us fulfilment, pleasure, meaning, even joy,” writes Sarah Jaffe in her book, Work Won’t Love You Back. “The admonishment of a thousand inspirational social media posts to ‘do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life’ has become folk wisdom,” she continues.

Such platitudes suggest an essential truth “stretching back to our caveperson ancestors”. But these fallacies create “stress, anxiety and loneliness”. In short, the “labour of love . . . is a con”. This is the starting point of Ms Jaffe’s book, which goes on to show how the myth permeates diverse jobs and sectors.

The book serves as a timely reminder of the importance of re-evaluating that relationship. “The global pandemic made the brutality of the workplace more visible,” the author tells me over the phone from Brooklyn, New York. Ms Jaffe, who is a freelance journalist specialising in work, points out that the past year of job losses, anxiety about redundancy, and excessive workloads has demonstrated to workers the truth: their job does not love them.

Work is under scrutiny. The economic fallout of the pandemic has made a great many people desperate for paid work, disillusioned with their jobs or burnt out — and sometimes all three. It has illuminated the stark differences between those who can work from the safety of their homes and those who cannot, including shop workers, carers and medical professionals, who have to put themselves in potentially hazardous situations, often for meagre pay. The idea of self-sacrifice, and that you should put your clients, your patients or your students before yourself, Ms Jaffe says, “gets laid on very thick [with] teachers or nurses”.

Yet there are those in another category — artists and precarious academics — for whom work has always been deemed intrinsically rewarding and a form of self-expression. They are said to be lucky to have such jobs, because plenty of others are clamouring to take their place. Even here, the pandemic has changed perceptions. Social restrictions have curbed some of the aspects of white-collar work that made it rewarding, such as travel and meeting interesting people, that perhaps masked the repetition of daily tasks, the insecurity or poor conditions.

Meanwhile, Ms Jaffe says, a small number of workers, such as those who have been furloughed on full pay, have been given the time to think: what do I do with the time I used to devote to work? “It’s so beaten into us that we have to be productive,” says Ms Jaffe. “I've seen so many memes that are like, ‘if you haven’t written a novel in lockdown, [you’re] doing it wrong’.”

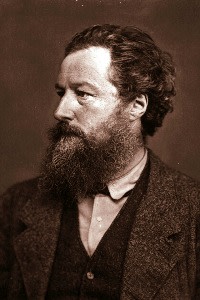

Among the affluent, work used to be something done by others, yet there have long been philosophical debates about whether it could be enjoyable. In the 1800s, Ms Jaffe points out in her book, the British designer and social campaigner William Morris pitched “three hopes” about work: “hope of rest, hope of product, hope of pleasure in the work itself”.

The decline of industrial jobs in the west, and the rise of the service economy, emphasised working for love. Nursing, food service and home healthcare, “draw on skills presumed to come naturally to women; they are seen as extensions of the caring work they are expected to do for their families”, Ms Jaffe writes. Among white-collar workers, the fetishisation of long hours in the late 1980s and 90s was accompanied by an individualistic capitalism. For many industries — notably, media — the idea of work as a form of self-actualisation intensified as security decreased.

Ms Jaffe says that there are overlapping experiences shared by those in the service sector who sit behind desks and those who stand on their feet all day. For example, the notion of the workplace as a family is a refrain in offices but it is most explicit for nannies. In the book, she tells the story of Seally, a nanny in New York who decided to live with her employers between Mondays and Fridays when the pandemic struck — leaving her own kids at home.

Seally told Ms Jaffe that she was worried about her own kids, whether they were doing their schoolwork properly: “At least I call and say, ‘Make sure you do your work’.” But she appreciates the importance of her job. “I love my work,” she said, “because my work is the silk thread that holds society together, making all other work possible”. The pandemic has reinforced the idea that the home is also a workplace and the author wants professionals who hire domestic workers and nannies to understand that and compensate accordingly for the critical role they play in facilitating their ability to do their jobs.

Perhaps the posterchild of insecure white-collar workers are interns, who have traditionally been unpaid. (In the UK, interns are eligible for pay if they are classed as a worker.) Too often, the book argues, interns have been given meaningless work with the prospect of a contract dangled in front of them, to no avail. Working conditions can also be poor — although few are as horrifying as the North Carolina zoo intern Ms Jaffe cites in the book who was killed by an escaped lion, “whose family told reporters she died ‘following her passion’ on her fourth unpaid internship”. The conditions for interns may be set back by the pandemic as so many graduates — and older workers hoping to switch industries — fight for jobs.

Ms Jaffe steers clear of advice. This is not a book that will guide readers on finding a job worthy of their devotion, though she knows that some glib tips would boost sales. “You’re told that you should love your job. Then if you don’t love your job, there’s something wrong with you,” she says. “[The problem] won’t be solved by quitting and finding a job you like better, or a different career, or deciding to just take a job that you don’t like.”

What she hopes is that people who have a nagging sense that their “job kind of sucks, they don't love it” will realise they are not alone. But they can do something about it, for instance joining a union or pushing for fewer hours. This needs to be supported by “a societal reckoning with jobs”. Do people need, for example, 24-hour access to McDonald’s and supermarkets, she asks?

Ms Jaffe wants people to imagine a society which is not organised “emotionally and temporally” around work. As she writes in the book: “What I believe, and want you to believe, too, is that love is too big and beautiful and grand and messy and human a thing to be wasted on a temporary fact of life like work.”

Letters in response to this column::

We’ve still to realise the Keynes working week / From Ira Sohn, Emeritus Professor of Economics and Finance, Montclair State University, Upper Montclair, NJ, US

How a soprano kept in tune with her dreams / From Alexandra Hamilton, Genoa, Italy

Comments