Unhedged: the FT’s new email on markets and finance

Simply sign up to the US equities myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome. This is the first edition of Unhedged, the FT’s new email which will land in inboxes each weekday morning. The topic is markets, and the people and companies that live and die by them. I hope to combine analytical rigour with plain-speaking and unvarnished opinion here, while having some fun. I hope you will join me for the ride.

Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox. Tell your friends and email me if you think I’m a hero, an idiot, both, or neither: robert.armstrong@ft.com.

Wild week last week? Get used to it

Last week was a doozy. The previous week’s lousy jobs report (economy cool, good for markets because loose monetary policy is more likely) was a set-up for Wednesday’s breakout inflation report (hot, bad, tight). It then turned into The Week We All Worried Even More About Inflation.

Stocks, especially growthy ones, got stomped like a narc at a biker rally. The Nasdaq fell 5 per cent between Monday morning and Thursday afternoon. Bond yields rose. Then on Friday, the fear dissipated, and things went almost back to normal. From my Reuters terminal:

Where does that leave us this week? Taking a deep breath.

Markets like to overreact, and it looks like they overreacted to that inflation number. My former colleague Matt Klein, of Barron’s, made a simple case for calming down. More than 60 per cent of the increase in inflation from the month before came from exactly the kinds of things you would expect to be transitory: “Used cars and trucks, hotels and motels, airfares, motor vehicle insurance, car and truck rental, admissions to live events and museums, and food away from home.”

Yes, we have to keep a close eye on wage increases and other indicators of sticky inflation in the coming months. No, it is not time to freak out.

Bulls like this point. Here is one, a private bank chief investment officer, as quoted by my colleague Katie Martin:

The bears are constantly looking for signs that the world is going to end. They come up with all the potential excuses. The reality is that the only question that matters is whether the reopening is going OK or not. And it’s going OK.

Bears sure are dumb! (After all, for a decade now they have failed to follow the one simple investing rule you’ll ever need: if you see a US stock, buy it). Yet there are at least two reasons, other than the universally acknowledged dumbness of bears, that the market is jumping at shadows. One is short term, and one long.

The short-term reason is that this market has quickly and aggressively discounted the accelerating economic growth that comes with reopening. But it will soon be discounting decelerating growth. Here is how Omar Aguilar, CIO of multi-asset strategies at Schwab, put it to me:

We are living the fastest cycle we’ve ever seen . . . markets anticipated that unprecedented recovery and GDP growth last year. If we think the deceleration GDP is coming, the market will be ahead of that, too. Would expect we see a pullback when we hit peak growth — we will hit the peak of this cycle before we know it.

Aguilar thinks peak growth may be a few quarters away. Others think it is happening about now. Here are the Goldman economics team’s estimates of quarterly GDP growth (the graphic is mine, in case you couldn’t tell):

My boss at the hedge fund I once worked at liked to say: always watch the second derivative. It is more fun to be invested when growth is set to accelerate than when it is set to slow. Here’s what the excellent economist Don Rissmiller of Strategas emailed me about the coming slowdown in GDP:

2Q is likely the peak in US real GDP growth . . . There’s also the possibility that 1Q 2022 sees corporate and personal taxes increase, which means there could be not just a slowdown, but a slowdown to below-trend growth temporarily as we start the new year. At a minimum, risk is rising as the year goes on due to the pace of vaccinations slowing (leaving open the possibility of another seasonal health issue by the winter), the large fiscal thrust passing, the possibility of the Fed starting the conversation on tapering, and tax increases.

Does that make you feel jumpy? Yeah, me too.

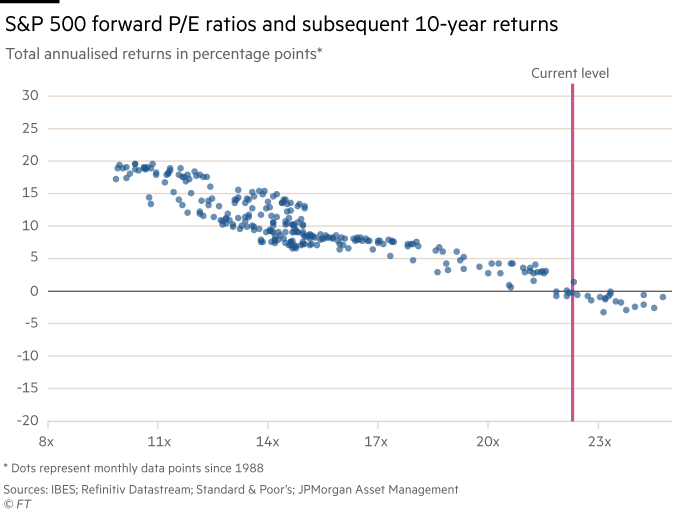

Now the long-term point. Here is a chart that ran in the FT a few weeks back, in a piece by Karen Ward of JPMorgan:

The relationship between valuations and subsequent long-term returns is imperfect, but is as strong as any predictive relationship in markets. If we know anything at all, we know that when you buy the market when it is very expensive, you won’t make much money in the long run. And where valuations are right now, history tells us that money we invest today will return, oh, nothing, give or take a few percentage points, annually over the next 10 years.

Valuations are useless, or worse, for telling you when to sell. If you sell and miss out on the euphoric moments at the end of a bull market, you are almost certain to underperform over time. There is no good reason we can’t have a face-melting rally starting tomorrow.

But knowing that you have to own stocks in the short term, and cannot rationally expect good returns over the long term, is a formula for investor nerves. Get used to weeks like last week. It’s gonna be a weird couple of years.

One good read

I have just finished Noise, the new book from Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass Sunstein. It’s not as great a book as Kahneman’s towering Thinking, Fast and Slow, but it makes a very important point. The random scattered errors (noise) in our judgments are at least as damaging and common as the predictable, non-random errors (bias) in them. Thanks largely to Kahneman, smart investors think all the time about bias and how to eliminate it. They should think about noise just as much.

Comments