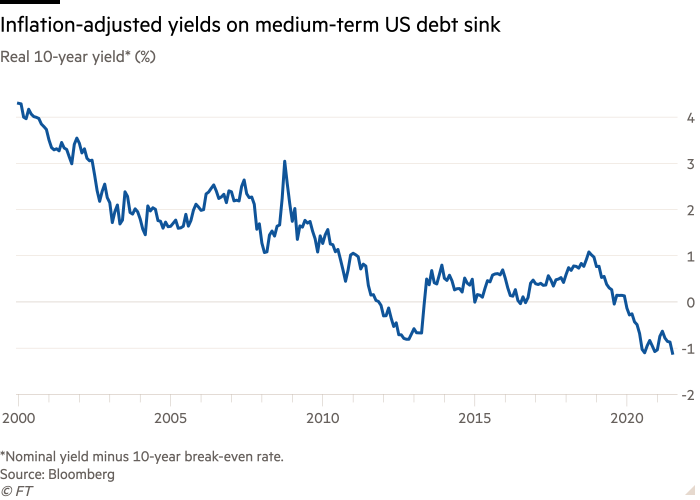

US real yields hit record low on growth concerns

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The returns investors expect to earn after inflation on the world’s most important government bonds have reached a record low in a fall that has had sweeping implications across global markets.

The real yield on 10-year US Treasuries fell further below zero on Monday as growing anxiety over the outlook for economic growth added fuel to a recent rally in bond markets.

The real yield — which measures the returns investors can expect once inflation is taken into account — sank to minus 1.127 per cent as a stock market sell-off drove Asia investors into the safety of government debt.

Real yields in the eurozone also traded at all-time lows on Monday, with the 10-year real interest rate swap — a key gauge of future interest rates across the currency bloc — hitting minus 1.65 per cent.

Negative real yields pose a big problem for pension funds and other long-term asset allocators that are also grappling with equity markets trading at high valuations.

One effect of deeply negative real yields is to buoy a range of other asset classes, as they make the returns they offer more attractive in comparison to bonds. Last year, investors said record-low real yields were driving an “everything rally” from gold to stock markets.

A relentless advance in bond markets over the past few weeks has surprised many investors, who had been betting on a further rise in yields after a big sell-off at the start of the year.

While many have pointed the finger at investor positioning and thin summer trading conditions to explain the moves, they have also been fed by a reassessment of optimistic global growth expectations as the Delta coronavirus variant spreads.

Nominal bond yields have fallen sharply from their highs in March at a time when inflation expectations have dipped only slightly, driving real yields beneath last year’s record trough.

The US 10-year break-even rate — the gap between real yields and nominal yields that serves as a gauge of investors’ inflation expectations over the coming decade — was at 2.33 per cent on Monday, down from levels of more than 2.5 per cent seen in May but still higher than the Federal Reserve’s 2 per cent target.

“Even though the underlying growth backdrop is very strong, the market has moved from thinking about reflation to maybe a little bit of stagflation fear,” said Jamie Fahy, global macro strategist at Citi, referring to a combination of low growth and high inflation.

The unease in markets is building ahead of Wednesday’s Fed policy meeting, at which chair Jay Powell may offer clues about the US central bank’s timetable for winding down its bond-buying programme, which has supported markets through the pandemic. Traders have scaled back their expectations for how quickly the Fed will raise interest rates amid a more uncertain economic outlook.

The prospect of rock-bottom rates for longer is a recipe for falling real yields and signals that the Fed — and other central banks — will be more tolerant of a rise in inflation expectations, according to Peter Chatwell, head of multi-asset strategy at Mizuho.

“Real yields are telling us the truth about how Fed policy will translate into considerably higher inflation over the medium term,” he said.

Comments