Buffered ETFs make gains in retirement portfolios

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

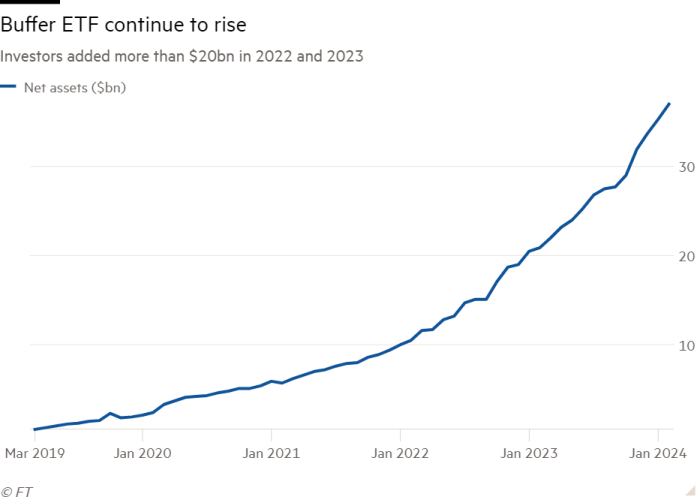

Retirement-focused investors have poured more than $20bn into US exchange traded funds that cap gains but limit losses over the past two years, posing a competitive challenge to established offerings from insurers.

Defined outcome or “buffered” ETFs use derivatives to limit the impact of bear and bull market extremes. Since debuting in 2018, they have become increasingly popular with investors who have weathered pandemic-related market turbulence in 2020 and a down year for stocks and bonds in 2022.

Those rocky periods have increased the appeal of the downside protection embedded in buffered ETF, meaning more investors are willing to pay a premium for exposure to US equities in a structure that limits the potential losses that could damage their nest egg.

US financial advisers are now increasingly willing to use buffered ETFs in client portfolios, helping them to attract $10bn in net inflows in both 2022 and 2023 at the expense of the $3.3tn US annuities market as well as pricey structured notes that offer to protect principals or guarantee minimum returns.

“These products are taking share from other means of getting similar outcomes, notably in the case of structured products and index-linked annuities,” said Ben Johnson, Morningstar’s head of client solutions.

There are now more than 200 defined outcome ETFs in the US with about $37bn between them, a sharp rise from five years ago when only $500mn was shared between about a dozen products, according to data from Morningstar Direct.

“As more investors enter or live through retirement, they’re wanting a semblance of control, or at least a feeling of relative security,” Johnson said, and are gravitating towards products that come with guard rails to protect against precipitous falls.

Surging investor interest in these ETFs has spurred large asset managers such as BlackRock and AllianceBernstein to enter the market to compete with established buffered ETF issuers, including Innovator Capital Management, First Trust and Allianz.

Stuart Chaussée, a Beverly Hills-based adviser, has moved more than 70 per cent of the $375mn he manages for his clients into buffered ETFs since late 2022, and he said he expects to keep using the products for the rest of his career.

“It’s a way for conservative investors, or those nearing or in retirement, to stay invested in stocks and get some decent upside,” Chaussée said. “You eliminate, for the most part, really large drawdowns in the portfolio.”

A typical buffered ETF might offer protection of 10 per cent against losses, meaning that if the US equity market was to fall 15 per cent in a given year, investors would lose 5 per cent. The flipside is that investors would not be able to take full advantage of a boom year, potentially seeing their gains capped at only 15 per cent or so in a year in which the S&P 500 rises by more than this, depending on an individual ETF’s upside cap.

“You still get that protection on the downside, but you don’t give away the upside potential of equities [entirely] because you’re still going to live for quite a long time,” said Johan Grahn, head ETF market strategist at Allianz Investment Management. “If you have 10, 20, 30 years left to live, you don’t say goodbye or goodnight to equity returns completely.”

A Morningstar analysis last year found that typical structured products’ sales costs were equivalent to management fees of well over 1 per cent, and annuities can cost even more.

However, buffered ETFs tend to be considerably more expensive than plain, vanilla ETFs — most passive ETFs tracking the S&P 500 charge less than 0.1 per cent, while Innovator, First Trust and Allianz generally charge more than 0.7 per cent for a defined outcome ETF — and some question their utility.

“You give up a lot of returns that you could have accrued for your clients,” said Elisabeth Kashner, director of global fund analytics at FactSet. Her analysis of one buffered ETF with 9 per cent annual downside protection found that investors would have forfeited nearly 6 per cent in annualised total returns since April 2020 for their peace of mind.

“The protection that they offer is limited and expensive, and I do worry that advisers haven’t taken that into account fully,” Kashner said.

Johnson said: “They absolutely work as intended. Whether they work as people expect them to is another question entirely.”

Even an advocate such as Chaussée said he would not want to invest new money in a buffered ETF amid a crash or bear market because it would not make sense to cap upside before a potential recovery.

He argued that the strategies’ relatively high fees could become more of a factor if upside caps became overly restrictive, but said the products are sophisticated and popular enough for now to ward off most concerns over cost.

“You can’t do it yourself. I looked into that and I talked to the subadvisers who manage the option contracts. It’s basically impossible to do it yourself, and it’s not tax efficient.”

Comments