Meet the cobots: humans and robots together on the factory floor

Simply sign up to the Aerospace & Defence myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Walking across the floor of SEW-Eurodrive’s factory in Baden-Württemberg is like moving through a time warp.

On one side, the light is dim and workers stand at long assembly lines repeating the same task over and over. On the other, a fleet of low-lying robotic trucks scoot around the shop floor, restocking restyled workstations.

In these small cells, a single employee helped by a robotic workbench assembles a virtually complete drive system that will be used to power the production of everything from cars to cola. Elsewhere, a robotic arm called Carmen helps workers load machines or pick components out of bins.

Here, the light is brighter, and the workers say they are happier. “Everything is just where I need it. I don’t have to lift up the heavy parts,” says Jürgen Heidemann, who has worked at SEW for 40 years, since he was 18. “This is more satisfying because I am making the whole system. I only did one part of the process in the old line.”

————————-

————————-

Mr Heidemann is one of a new breed of industrial employees, learning to work side by side with the latest generation of robotic systems. Traditionally, industrial robots have been locked behind cages, their heavy bulk and rapid movements making them unsafe for human interaction. They have required highly trained programmers to set their tasks and, once installed, were rarely moved.

Now, a lighter weight, mobile plug and play generation is arriving on the factory floor to collaborate safely with human workers thanks to advances in sensor and vision technology, and computing power. Get in their way and they will stop. Program them with a tablet or simply by moving their arms in the required pattern; no coding is necessary. And if the robot is needed in a different part of the factory — unlike the heavy robotic arms that populate the world’s automotive factories and are bolted to the floor — they can be easily moved.

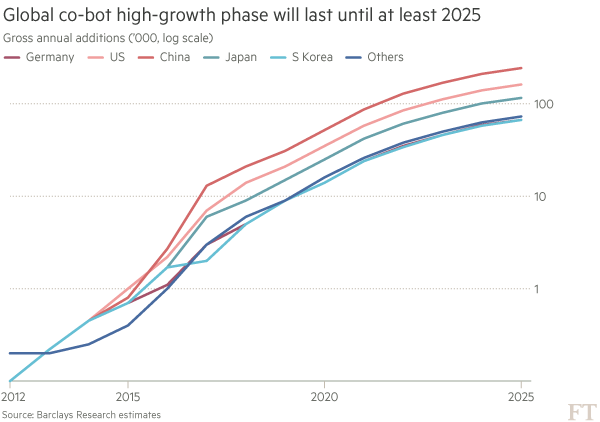

Cobots, the name to collaborative machines such as these, are so new they account for just a fraction of global industrial robot sales: less than 5 per cent of the record 240,000 sold last year.

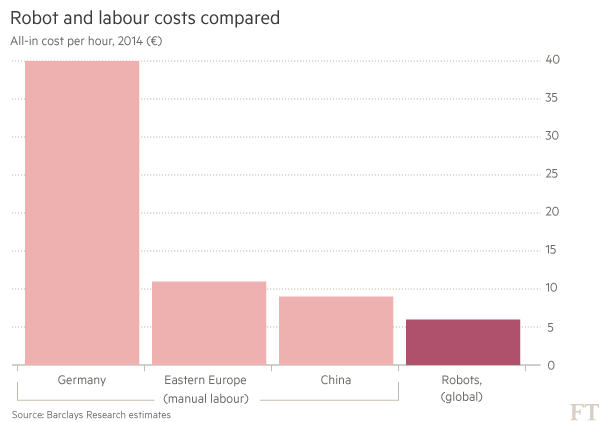

But manufacturers say these flexible robots — at average price of $24,000 each according to Barclays — have the potential to revolutionise production, in particular for smaller companies that account for 70 per cent of global manufacturing.

Most companies have struggled to automate given the high cost associated with traditional robotics. Yet with the average factory worker earning $11.80 per hour in the US and £7.40 in the UK, according to salary comparison website PayScale, a payback at these lower price levels can be a matter of months. James Stettler, an analyst at Barclays Capital, estimates the cobot market could grow from just over $100m last year to $3bn by 2020.

“A lot of people have been waiting for this kind of breakthrough,” says Jesse Rochelle, manufacturing engineer at Stenner Pump, a Florida-based company employing 90 people. Stenner acquired Baxter, a two-armed cobot made by Boston-based Rethink Robotics, 18 months ago.

The company’s new worker is being used to feed parts directly from manufacture into packaging, reducing human handling by 75 per cent. As Baxter does not have to work behind a fence or stop every time a human comes into proximity, Stenner’s employees can get on with other work. “We have significantly reduced the cycle time from raw material to finished product,” he says.

Mr Rochelle adds that low-cost collaborative robots are a boon to small and medium-sized companies such as Stenner that have to compete against rivals from low-cost markets. “The use of cobots in small companies may . . . at a minimum allow jobs to remain local,” he says.

Yet there is no escaping the fear that the arrival of robots on the shop floor could render large sections of the human workforce redundant. Economists Carl Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford university have estimated that close to half of US jobs could be at risk from automation.

The emergence of highly adaptable robots could heighten that risk. Advances in gripper technology, machine learning and artificial intelligence will inevitably help to rectify some of the weaknesses of today’s cobots. Handling wires, textiles or changing tasks remains a challenge for industrial robots. One study found that it took 20 minutes for a robot to fold a towel, for example.

Companies deny that cobots will replace workers, describing them instead as aides for the “dull, dirty, and dangerous” jobs that humans dislike or are ill-equipped to do. Yet many are reluctant to show off their robotic workers, perhaps for fear of drawing adverse publicity as they explore the ways in which this new labour force can be used. Several refused the Financial Times’ request to see them in action.

Many unions have not even begun to consider the implications of human-robot collaboration on their members. “It is going to happen and the job losses could be horrendous in some areas,” says Tony Burke, assistant general secretary of the Unite union. “But the problem is that nobody really knows.”

Joe Shelton, a manager at carmaker Nissan’s plant in Tennessee, says material handlers were anxious when autonomous guided vehicles were introduced into the factory. “They felt like we were taking their jobs,” he says. Now, however, “they are very receptive to them. They work hand in hand.” No one was laid off, he insists, and instead the 30-year-old factory’s working life has been strengthened. The time needed to reconfigure for a new model has been cut from more than a year to a matter of days thanks to the more flexible robotic logistics system, he says.

At Airbus, the European aircraft manufacturer, a mobile robot strapped to the side of a fuselage drills the tens of thousands of holes needed to hold a passenger jet together while humans work beside it.

————————-

Read more

Automated workers: what every manager should know

Andrew McAfee on why it is wrong to worry about robots taking over

How robots can make it quicker to buy a house

————————-

Stéphane Maillard, who for 13 years has worked on aircraft assembly, says the robot has not replaced his job. “It has changed the way of working,” he says “Before it was very manual. Now it is more about piloting the robot. 100 per cent of our operators would never go back.”

The group is testing a robot on wheels that will move around inside the aircraft to label where workers have to install brackets — a position that must be accurate to within the millimetre.

Humans might take heart from the recent decision by Mercedes-Benz to replace robots with humans on some lines. The machines were just not agile enough to keep pace with the growing demand for customised products while we humans can “reprogram” ourselves in a fraction of a second. “We’re moving away from trying to maximise automation, with people taking a bigger part in industrial processes again,” says Markus Schaefer, head of production planning at the automaker. “When we have people and machines co-operate, such as a person guiding a part-automatic robot, we’re much more flexible and can produce many more products on one production line. The variety is too much to take on for the machines.”

Scientists at the MIT have proved the veracity of Mercedes-Benz’s experience. Working with another German carmaker, BMW, researchers found that robot-human teams were about 85 per cent more productive than either alone.

Back in Baden-Württemberg, Mr Heidemann is confident that his humanity will guarantee his own job — no matter how clever the machines become. The task of putting together a gear motor is more delicate than it looks. “You need dexterity, you need feeling. A robot would damage it,” he says.

Then again, the long-term future is not really his concern. “I retire in six years,” he says with a wide grin. “In those six years it ain’t happening.”

Comments