Higher inflation is coming and it will hit bondholders

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is professor of finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

When oil prices sank to zero last May, few investors thought of inflation. But those who study data on monetary conditions knew that the unprecedented build-up in liquidity would see the economy boom and prices rise as soon as vaccines put an end to the pandemic.

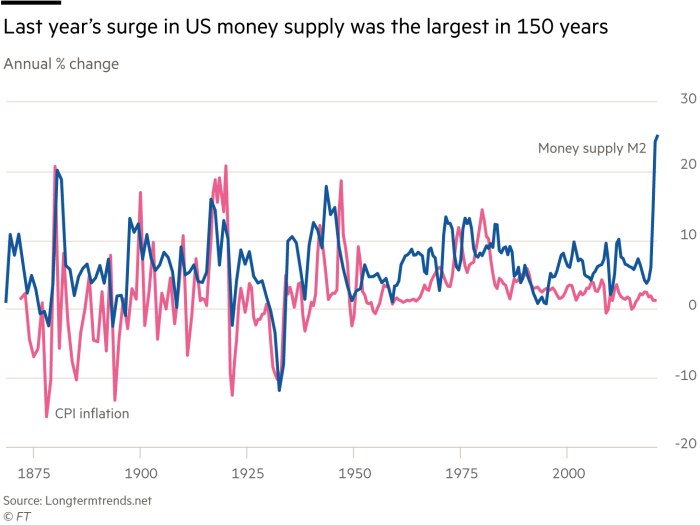

The monetary data are striking. Between March and November, the measure of broad-based money supply, M2, jumped by a sharp 24 per cent. Shockingly, the money supply surge in 2020 exceeded any in the one-and-a-half centuries for which we have data.

Monetary expansion has also been robust in much of the rest of the world, but nowhere nearly as pronounced as in the US. And the new Biden administration will surely provide even more fiscal stimulus.

One of the oldest propositions in economics is that the price level is determined by the demand and supply of money. Simplistic formulations of this proposition are called “The Quantity Theory”. This proposition states that the rate of inflation is equal to the excess of the rate of growth of money over real incomes — although more sophisticated interpretations take into account other variables such as interest rates and inflationary expectations.

But while many investors acknowledged that the huge increase in liquidity in 2020 was being funnelled into the stock market, few investors feared inflation. Most noted that the US Federal Reserve had engaged in significant monetary expansion, known as quantitative easing, following the financial crisis. Despite warnings by many economists then of rising consumer prices, inflation did not follow, and actually declined.

However, there was a fundamental difference between what happened during the financial crisis and what is happening now. The money created by the Fed during the last financial crisis found its way into excess reserves in the banking system. Little of it was lent out to the private sector.

This happened because, before the Lehman collapse, banks did not hold excess reserves. At that time, reserves paid no interest and prudent reserve management dictated that banks keep the absolute minimum to satisfy reserve requirements. All excess reserves were lent into the money market.

The financial crisis changed all of that. Following the crisis, interest rates collapsed. The Fed started paying interest on reserves, and regulators imposed liquidity requirements that could be satisfied with these reserves. The banks easily absorbed the extra reserves created by the Fed and quantitative easing led to only a modest increase in lending.

But the actions of the Fed and Treasury in response to the Covid-19 crisis are producing a very different outcome. The money created by the Fed is not going only into excess reserves of the banking system. It is going directly into the bank accounts of individuals and firms through the US Paycheck Protection Program, stimulus cheques, and grants to state and local governments.

In the mid-1970s, I was a young assistant professor at the University of Chicago during the final years of professor Milton Friedman’s distinguished career. I remember him telling me that aggressive expansion of the reserve base is a powerful force, and would have saved us from the Great Depression of the 1930s. But if expansion of reserves actually reaches saving and checking accounts of the private sector, such Fed action is many times more powerful.

Those words informed my optimistic forecast last summer as the pandemic deepened. I said that the US was going to experience a strong stock market in 2020 and an extremely inflationary economy in 2021.

I certainly do not expect hyperinflation, or even high single-digit inflation. But I do believe that inflation will run well above the Fed’s 2 per cent target, and will do so for several years.

This is not good for bondholders. The huge demand for Treasuries, which has kept their yields so low, is driven by their strong short-term hedge characteristics — their ability to cushion sharp declines in risk assets.

But this insurance is going to get more and more expensive as higher consumer prices erode the purchasing power of these bonds. It is inevitable that bond rates will rise, and rise far more than now envisioned by the Fed and most forecasters.

The multi-trillion dollar war on Covid-19 was not paid for by higher taxes or bond sales to the public. But there is no such thing as a free lunch. It will be the Treasury bondholder, through rising inflation, who will be paying for the unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus over the past year.

Letter in response to this article:

Printing money is not under way, at least not yet / From Dan McLaughlin, Dublin, Ireland

Comments