Virgin group: Brand it like Branson

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Sir Richard Branson is a mass of contradictions. A man who often appears shy, yet has built a brand around his charisma. Someone who vaunts his social conscience, but who lives as a tax exile on Necker island. A fervent environmentalist, who wants to send wealthy travellers into space.

One of the biggest inconsistencies is that his public persona – that of an entrepreneur running a multifarious business empire – does not reflect reality. In fact, Sir Richard manages very little. His Virgin Group owns stakes – few of them majority ones – in a vast range of businesses, but as an investor rather than a manager. Indeed it most resembles a huge “family office” with a portfolio run by professional investment managers and the profits channelled – via a number of trusts and a network of holding companies – to the Branson family.

The crash of the Virgin Galactic spacecraft on Friday and the death of one of its pilots strike at the heart of the contradictions of the Virgin empire, contradictions which show that it is less robust than it might appear.

“Richard is interested in what is happening in the investment portfolio, but doesn’t run any of the businesses in it,” says Josh Bayliss, chief executive of Virgin Group Holdings, which manages Sir Richard’s investment portfolio and the Virgin brand. “His attention on a day-to-day basis is not on the operational aspects of the businesses.”

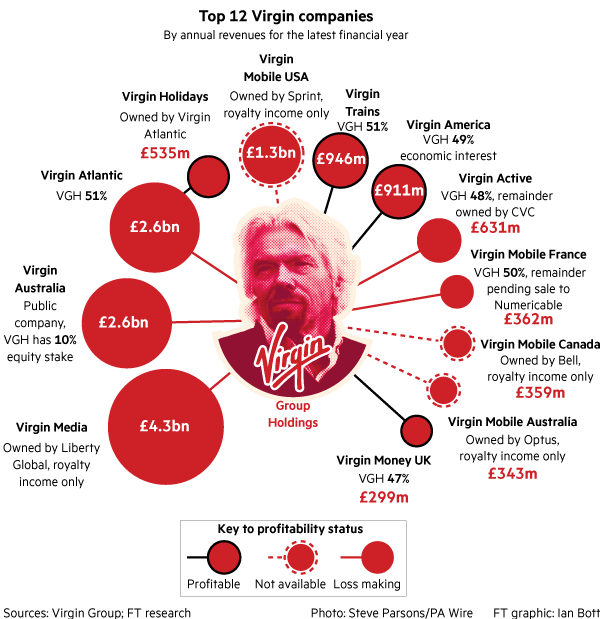

Of the about 80 businesses which bear the Virgin name, spanning sectors from travel, transport, leisure, entertainment, telecoms and media, less than half have direct stakes held by Virgin Group. Virgin companies made £15bn in revenues in the past financial year, but these bear little relation to the value or performance of the holding company. VGH owns 27 per cent of the 12 largest Virgin companies by revenues.

And those group companies are not even the most significant holdings in its investment portfolio. Virgin Money, which is only the 12th largest Virgin company by revenue, accounts for 15 per cent of the portfolio, with Virgin America at 10 per cent, followed by Virgin Active, Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Mobile France.

VGH makes a significant amount of its money not from cash flows from its investments – particularly since a number of large Virgin businesses do not turn a profit – but from the fees it charges companies for lending them the Virgin name. The Branson family’s wealth, therefore, is dependent on the value of the Virgin brand which is intimately linked to Sir Richard himself.

“Every day that Richard gets older the issue of the Virgin brand becomes a bigger one because so much of it is tied to him,” says Jez Frampton, chief executive of Interbrand, the brand consultancy.

Since 2005, Sir Richard, 64, has stepped back from day-to-day running of Virgin Group Holdings, to focus on his charitable activities and space tourism.

With Virgin Galactic, he hoped not just to send people into space, but also harness his personal brand and that of the Virgin name to boost franchising opportunities, especially in the US.

For Galactic’s business model, Virgin followed a well-worn route. The group’s favoured start-up model relies on private investment for financing, with generally a co-investor sharing equity, and therefore the financial risk, often with a large amount of debt to the parent company loaded on to the balance sheet, a model it has followed at most of its businesses since the group’s brief but painful experience as a London-listed company in the 1980s.

So far, Virgin says, Galactic has sucked in up to $600m of investment, $380m of which was provided by Aabar, Abu Dhabi’s state investment agency. The Aabar money has now been spent, but Virgin says its partner is not expecting a swift return on its money nor pressing for an exit.

The structure of the Virgin Group allows cross-subsidisation of its different businesses. Now that Virgin Galactic has burnt through the Aabar investment it is being financed from cash held by VGH itself. Virgin will not confirm that this has diluted Aabar’s equity, suggesting that the bulk of the additional financing is in the form of debt. Mr Bayliss says Virgin is not seeking an additional equity injection from Aabar, nor a new equity partner for the venture.

Space dream

Sir Richard has vowed to continue testing spaceships and seems to have no plans to abandon Galactic. The commercial launch was scheduled for next year, which seems ever more unlikely, but on Wednesday the company told the Financial Times that only 3 per cent of the about 700 people who had signed up for a ticket by paying a $20,000 deposit or the $250,000 full fare had asked for a refund.

If Sir Richard did decide to abandon Galactic, repaying Aabar’s $380m investment, the $89m in advance ticket sales and the hit to its own balance sheet of $220m-plus, would not be overwhelmingly onerous for the group, given VGH’s portfolio is valued at more than £5bn. Continuing with it, though, is a rather different matter.

Because VGH is run like a private equity company the question is how secure are the cash flows to bankroll Galactic and other Virgin businesses, which are at varying stages of development and profitability. How long can VGH sustain the cash drain?

Sir Richard told the FT last month that the group was “in the strongest position it’s ever been in”, “cash-rich” with no net borrowings. It is also pressing ahead with the initial public offering of Virgin Money, which owns the “good bank” assets from failed UK mortgage lender Northern Rock, and of Virgin America, the US airline in which it has a 22 per cent stake, lodging its prospectus with the Securities and Exchange Commission on Monday.

Virgin America only returned to profit in 2013. Its listing – which the owners hope will value the airline at up to $1bn – will allow the repayment or conversion into equity of at least $650m of related-party debt plus the accrued interest on it – owed to Virgin Group and its co-investor, Cyrus Capital, a distressed debt fund manager.

Virgin says the bulk of the cash proceeds will remain in the business to finance future growth, but it will nevertheless provide VGH with some useful cash in hand.

In the private equity world, such financial arrangements are not unusual before an investment is exited. But as no interest has been paid on the debt on Virgin America’s balance sheet since its start-up in 2007, it is difficult to assess the profitability of the business.

VGH does not disclose the amount of cash in its portfolio, although it says there are “several hundreds of millions of dollars” available. The group’s value relies on the capital appreciation of its investments. But its income is made up of a share of dividends and cash flows from those investments, including service on the debt it lends down the network of holdings, the proceeds of refinancings, sales or listings and the revenue stream from licensing the Virgin name.

There is nothing illegal about Virgin Group Holdings using cash or its stakes in other Virgin companies to support other branded businesses. But it makes it difficult to assess their genuine sustainability, and may skew management decisions – to the detriment of minority shareholders – if cash is needed in another part of the portfolio.

Damaged goods

An even bigger question hanging over VGH and the other companies bearing the Virgin name is what damage last week’s fatal crash will do to the value of the businesses.

Interactive timeline

Virgin: 44 years of brand-building

Richard Branson’s golden touch has helped him grow a mail-order record service into a global conglomerate of 80 Virgin-branded companies. He has juggled spaceships, mortgages and video games, and now ranks seventh on the Forbes UK billionaires list. Forty-four years after Mr Branson opened the first business, Virgin Group’s net worth is now estimated at £5-5.5bn.

Virgin America has been explicit on the subject: “The ‘Virgin’ brand is not under our control, and negative publicity related to the Virgin brand name could materially adversely affect our business,” it warns in its IPO prospectus.

Sir Richard had hoped Galactic would have a “halo effect” on the rest of the company. The risk is that it will have the opposite impact and threaten the value of the brand upon which the whole edifice depends.

Mr Bayliss says that royalties – income from allowing companies to use the Virgin brand name – have increased substantially in recent years and their weight in the overall VGH investment portfolio has risen accordingly. Revenues from the brand, which are mainly licensed by Virgin Enterprises, now amount to about £120m a year. The brand is valued on a discounted cash flow basis at roughly £1bn, and it thus accounts for a significant proportion of VGH’s overall value of £5-5.5bn.

Virgin has focused most of its expansion plans in North America in recent years and had hoped to use the Galactic operation as a way to grow the appeal of the brand in a country where Sir Richard has struggled to raise his profile.

“[Sir Richard] is quite well known in New York because of Virgin Atlantic but once you get beyond there, he’s not,” says Mr Frampton of Interbrand.

Mr Bayliss argues that the Virgin brand stands on its own two feet. “If you rebranded Virgin Atlantic as, say, Cloud Airways, they would pay less in royalty fees, but strategically and operationally the business would continue to do the same things, although without the benefits of the ‘Virgin’ name,” he says. “In the UK it’s more true than anywhere else that Richard contributes to the [Virgin] brand perception. But it’s a very very mature diverse brand which stands for different things in different markets.”

It is a moot point whether the Galactic crash will combine with previous failed attempts to boost the Virgin brand in North America and reduce the potential growth of VGH’s royalties income.

Although it has had to lower the price it hoped to raise from Virgin Money, VGH says the crash has had no impact on the valuation range suggested for its Virgin America IPO. And is aware of the need to sustain the brand’s value.

“Over the past seven or eight years, since Richard has been less hands-on, it has been a very significant focus for us to build equity in the brand beyond Richard,” says Mr Bayliss.

The Virgin founder has always been a dreamer who likes taking big risks. But with Galactic, the danger is that those risks undermine the structure that underpins the dreams – and finances the risks.

Additional reporting by Cynthia O’Murchu

Comments