China’s dreamers and dropouts: ‘lying flat’ generation checks out in Dali

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Unlike many Chinese people of her generation, Zhu Xiangjuan does not believe in saving money, nor does she like formal schooling.

Pouring tea in her rustic bookshop in Dali, in south-west China’s Yunnan province, the 40-something mother of one explains that she sends her child to a home-schooling group instead where they learn “naturally” by reading Confucian tomes.

“The younger children will follow the older ones, the older ones will follow their parents, it will come naturally,” she said, smiling disarmingly.

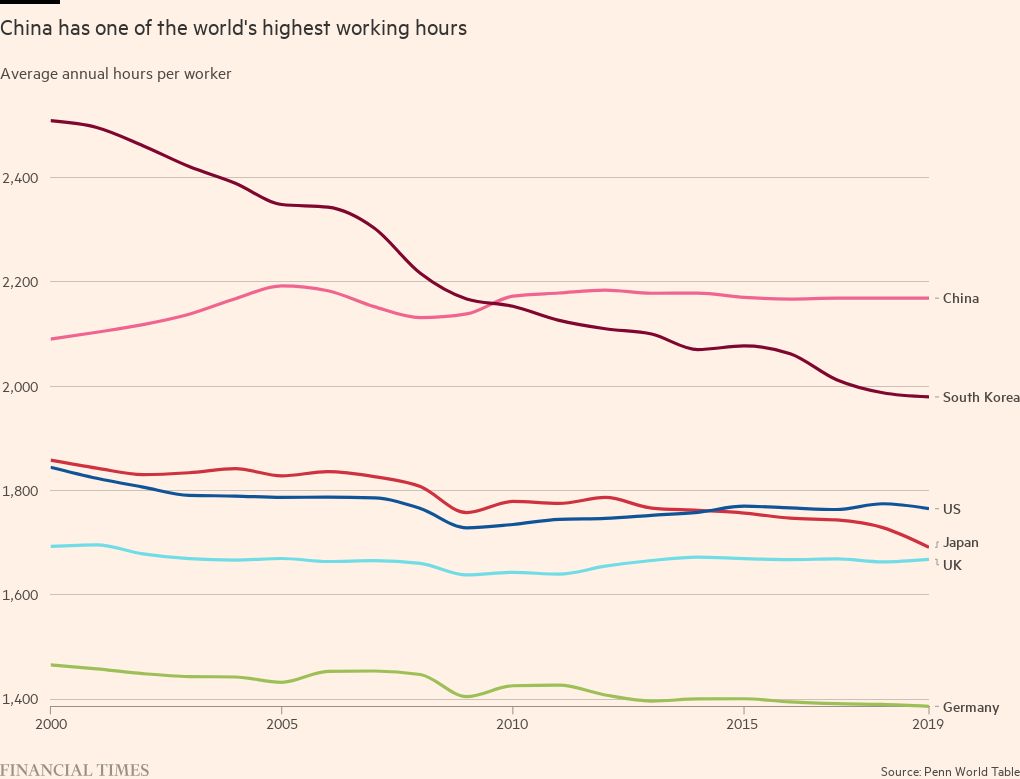

Zhu’s views might be radical for China, which has one of the world’s highest savings rates and where parents compete to send their children to the most prestigious colleges — but they are not unusual in Dali.

The lakeside city, with its historic ethnic Bai courtyard homes and eastern Himalayan scenery, is attracting an increasing number of social and intellectual refugees from the yali, or pressure, of China’s megalopolises.

The pandemic and a slowdown this year in the world’s second-largest economy, along with China’s increasingly austere political atmosphere, have accelerated the trend.

China’s leader Xi Jinping wants the country to climb the technological ladder so that it can rival the US. There is little space for alternative visions of the future, or for protest, making refuges such as Dali important for those who are stressed, fed up or simply think differently, according to those who live there.

“[In Dali] you can have many friends and it’s easy to meet people with an accepting and open mindset,” said Gao, an entrepreneur from China’s southern tech hub of Shenzhen, who started coming to Dali this year. He said the broader society there was “tolerant and understanding”, allowing an “ideal state where you can freely be yourself”.

Café culture and alternative lifestyles

Gao likes to meet visitors at Six Yuan Café, where a decent coffee costs Rmb6 ($0.84) — about a fifth of the price in China’s biggest cities. Patrons scrawl poems in a guest book, some about existential angst. “Growing up is equivalent to getting sick,” reads one.

Basking in the shop’s sunny courtyard — at an elevation of 2,000 metres, subtropical Dali is renowned for its agreeable climate — Gao explains that dreamers and dropouts have been coming here for decades but this reached a critical mass during the pandemic, when digital nomads flooded in. He estimates there are now about 100,000 “alternative-minded” people in the Dali prefecture, whose population is 3.6mn.

These include those doing tang ping, or “lying flat”, usually young people who reject societal pressure to work long hours, buy overpriced houses and marry and have children. They tend to be middle-class people from single-child families who can spend up to a year doing nothing in Dali, bankrolled by parents or grandparents.

“For our post-90s generation, when they step out of university, our economy has shifted from high speed to slow growth,” said Gao. “They see no possibility of owning a home, settling down, and living contentedly, leaving them directionless and aimless.”

When they come to Dali, “initially, it’s [for] ‘lying flat’ — a passive stance”, said Gao. “But these are young people — inherently vibrant, passionate and aspirational,” he added. Once their parents’ money runs out, those who want to stay look for low-key work, such as selling trinkets to tourists in Dali’s old city.

At this point they become what Gao calls lüju, meaning people who are still exploring but moving towards a more fulfilled state. This group also includes older people in their forties, who come to escape “brutal competition” in the cities but have more money and life experience, he said.

“So, the main newcomers in Dali are these two types [tang ping and lüju]. Their primary need is economic stability . . . It’s not like in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, where earning money is the primary goal,” he said.

Gao has another message — appropriately for Dali, it is one of peace. In an age of east-west competition, China can still pursue its own future without falling into confrontation with the US. “I’m in the middle camp,” he said. “Neither absolutely pro-west or anti-west.”

Creative rebellion on Renmin Road

A few kilometres away in Dali’s Ancient Town, the region’s old capital where tourists sample hotpot containing an array of Yunnan’s wild mushrooms, young people post notes on a board outside a shop.

“I have always been trying to make money, but after three years of the pandemic I finally understand that I don’t like fame and fortune and the cement boxes and glass shells of the city,” said one note.

At night, young people line old Dali’s Renmin Road, selling jewellery made from seeds taken from the forest, or virtually anything else they can find.

A woman marketing trendy socks displayed on a cloth said she previously worked as a nurse in the western megacity of Chongqing but disliked the long hours. She now makes between Rmb50 and Rmb100 per day on Renmin Road, “which is usually enough for me thanks to Dali’s low cost of living”.

Dali’s cheap prices are an important attraction. Xiao Bao, who works as a freelance market researcher in Shanghai, visits Dali regularly, where she practises contact improvisation, a form of dance.

Her rented timber house with outdoor toilets, compost and recycled water costs about Rmb1,800 a month — very cheap compared with Shanghai. “Dali is quite special in China,” she said. “It’s possible to live a more sustainable life here.”

Others come to Dali in search of new ideas. Yang Kai, a friend of Gao’s, is from Maotai township, the town where China’s famous liquor is made. His family are also distillers, but Yang said he does not want to start his own distillery. “I want to do something more creative.”

A haven under pressure

But idyllic Dali is changing fast as China’s mass tourism floods in. By Lake Erhai, honeymooners take selfies in flamingo-pink BMW convertibles, while boutique hotels with pristine white lobbies line the lake’s shores. The influx of people is driving up costs and one street seller in Dali old town said she sometimes could not afford to buy fruit. Some newcomers said relations with local ethnic Bai people could be tense as villagers sought to capitalise on the influx by putting up rents.

China’s omnipresent police state is watching too. A digital nomad conference with art and tech-related seminars was abruptly cancelled last month, Reuters reported, citing sources who attributed the move to a sudden withdrawal of support by the government.

President Xi Jinping dislikes the concept of “lying flat”, instead urging young people to “eat bitterness” or embrace hardship, as Mao Zedong forced his generation to do during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s.

But some warn that discontent among the country’s youth is in danger of boiling over. “Young people today feel a strong sense of deprivation as they are having trouble moving up the social ladder,” said a government adviser in Beijing. “We should give young people a channel to voice their anger. That could prevent massive protests from happening.”

Gao said the government was focused on “national rejuvenation” — restoring China’s pre-colonial stature in the world — and did not believe this was the right time to “take a breather”.

However, the emergence of hubs such as Dali, where people can take a break and find an alternative path, provided an important release, especially for the young, he said. “Staying in big cities could lead to a lot of grievances and complaints.”

The government need not fear as Dali will never become “mainstream”, he said, “but it will exist and grow in a corner” — a haven of diversity for eccentric bookshop owners, retired tech entrepreneurs and stressed-out nurses.

Additional reporting by Wenjie Ding

Letter in response to this article:

China will never match the US for one simple reason / From Mehdi Al Bazzaz, Former World Bank Economist, Alexandria, VA, US

Comments