ETFantasmagoria

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Back in 2016, then-Vanguard CEO Bill McNabb went to an exchange-traded fund conference to beg for restraint. If the proliferation of ETFs didn’t slow, he warned, the consequences might be dire:

The industry is [introducing a new] ETF, it feels like, every 30 seconds. This is like the 1980s and mutual funds. Things did not end well for all those funds . . . We have to be very careful. If we go too far as an industry, people will have doubts about the original construct. And some categories are pretty esoteric.

Even Morningstar’s Ben Johnson likened the approach to blasting a spaghetti cannon at a wall and seeing what sticks. But seven years later we can safely conclude that the industry as a whole blew raspberries at the suggestion to take things slow.

When McNabb spoke the number of ETFs had gone up more than sixfold in the previous decade to over 4,845. A splurge of new ETFs last month — one of the busiest on record, according to Bloomberg — brought the global total to over the 10,000 mark at the end of September, according to ETFGI data. To put that in context, there are only roughly 5,000 truly liquid stocks globally.

And there are few signs of things slowing down. Already in October another 42 have been launched, almost two a day on average. Here they are, courtesy of Stockanalysis.com:

OK, many of the latest ones are perfectly fine — such as a brace of short-duration bond ETFs from Capital Group and Dimensional Fund Advisors, a large-cap US equity ETF from Avantis or some target-date funds from BlackRock — but this is getting silly.

Among the newest ETF babies there are:

— a handful of 200 per cent leveraged and inverse Tesla and Nvidia ETFs, because clearly the underlying stocks just aren’t volatile enough;

— an option-writing ETF focused on just a single stock, payments company Block (the company already offers similar ETFs for the likes of Tesla, Apple, Nvidia and Coinbase);

— A handful of crypto ETFs including several ethereum vehicles (a spot bitcoin ETF is probably coming soon as well)

— the “REX FANG & Innovation Equity Premium Income ETF”, which sounds like it’s going for a prize in the most amount of investor-titillating terms you can shove into your name, but is actually a covered calls strategy.

— the Arch Indices VOI Absolute Income ETF, which is an equities-plus-bonds ETF that uses Arch’s “proprietary Variance Optimized Indexing (VOI) methodology to weight each security by taking into account its Yield, Volatility, and Correlation to the portfolio”.

We hate to be Luddites, or deny upstarts a chance to take on industry giants, but the historical record for new-gen ETFs is . . . not encouraging. Here’s a killer paper by Itzhak Ben-David, Francesco Franzoni, Byungwook Kim and Rabih Moussawi published last year:

While early ETFs invested in broad-based indexes and therefore offered diversification at low cost, more recent products track niche portfolios and charge high fees. Strikingly, over their first 5 years, specialized ETFs lose about 30% (risk-adjusted). This underperformance cannot be explained by high fees or hedging demand. Rather, it is driven by the overvaluation of the underlying stocks at the time of the launch.

. . . Overall, our results suggest a new narrative for the evolution of the most transformative financial innovation of the last three decades. The early ETFs, which are broad-based products, are beneficial investment platforms, as they reduce transaction costs and provide diversification. Specialized ETFs ride the same wave of financial innovation, but they mainly compete for the attention of performance-chasing investors. Consequently, specialized ETFs, on average, have generated disappointing performance for their investors.

Of this 30 per cent five-year average underperformance, about 3 percentage points is explained by their mostly higher fees, and 27 percentage points is because of crappy results. Franzoni wrote about their findings in mainFT earlier this year.

One of the paper’s main charts is pretty stark (though NB the methodology at the bottom):

So will this all end badly, as McNabb feared back in 2016? For investors in most of these ETFs, probably (viz XIV) but for the industry, probably not. In fact, Alphaville suspects things are going to get much nuttier.

For a long time industry big beasts like BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street feared that some dumb ETF blowing up would land on the front page of USA Today or the Daily Mail and scorch the earth for everyone. That’s one of the reasons why they’ve generally been careful about launching new ETFs even when there is a demonstrable investor interest (forget about “need”), and have been quick to diss anything that does break bad as somehow “not ETFs”.

However, the reality is that investors do seem sufficiently discerning (or oblivious, potatoes potatoes) and don’t judge the entire ETF world whenever something turns out to be turd sprinkled with some hype and wrapped up by a sexy backtest.

Despite all the hype and attention paid to a lot of the gimmickier ETF launches, the vast majority of investor flows continue to be into plain-vanilla, cheap beta ETFs, as this chart from JPMorgan’s annual ETF handbook shows:

That’s almost certain to continue. ETF flows have been remarkably resilient in recent years despite rocky markets because many US savings plans now include the basic cheap ones. That means that even bond ETFs will automatically see inflows when returns are shocking.

And as Alphaville has written before, the ETF structure has long since outgrown its passive roots. It now being used to package up all kinds of active strategies — or bundles of financial risk of myriad sorts.

This is particularly noticeable in the US. Aside from the tax advantages, distribution of American investment products increasingly happens on various online investment platforms and via financial advisers. (so the stock-like ETF has an advantage).

This is why you’re seeing more traditional asset managers like Fidelity and Capital Group launch more ETFs or convert existing mutual funds into them. For example, one of this month’s launches was an ETF version of JPMorgan’s 26-year old Tech Leaders fund.

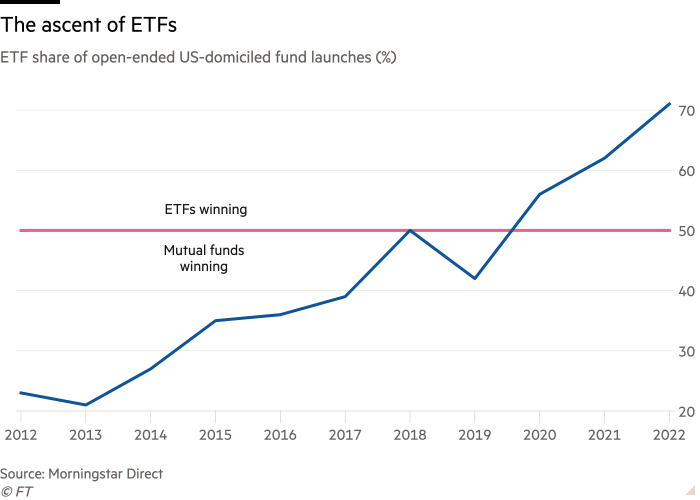

Here’s a chart from 2022 showing the shift.

The number of ETFs will continue to grow simply because of this dynamic (especially when/if Europe ever shifts from bank-dominated distribution to one where more investors buy funds on apps or through independent advisers). That’s not “bad” per se, it’s just one fund structure slowly supplanting another.

But above all, the flexibility of the ETF structure means that you can actually use them to package together pretty complex strategies or fine-tuned exposures and sell them at industrial scale.

In theory, that allows even hoi-polloi retail investors to build portfolios that just a decade ago would have been the preserve of a large institution, and gives even hedge funds a potent new toolbox to utilise (just look at Bridgewater’s latest 13F filing — three of its 10 biggest disclosed positions are ETFs).

You can kinda think of early investment strategies like Duplo. The building blocks were big, broad and there was a limit to how fancy you could actually get, even if you were a big institutional investor.

But your exposures were blunt, and sometimes there could be nasty surprises when it turned out that some polished hedge fund was actually just a levered bet on growth stocks, or that hot-hand fixed income fund was merely YOLOing junk bonds into a recession.

Institutional investors have generally gotten a lot more sophisticated since then, but for a lot of smaller ones — or retail investors — it can be tricky to go much further than the Duplo approach.

However, ETFs can potentially be used a bit more like Lego, to build more complex, bespoke portfolios with more specific exposures. Ie something more like this (NB very much not investment advice etc etc!):

Given everything that people are currently shoving into ETFs — and what we are likely see over the next few years — the future might look a bit more like this:

This is admittedly a pretty galaxy-brain level suggestion, and my conviction on this is not high. Most of the new ETFs being churned out today don’t really seem to fit even any vague investment need (if you don’t count an asset manager’s thirst for fees as need).

Nor is it a good idea for most ordinary investors to think that they should try to emulate a complex asset allocation model, just because they’re able to!

As JPMorgan’s Jan Loeys recently wrote, a long-term investor (retail or institutional) doesn’t actually need more than two assets in their portfolio: global equities and local bonds.

Our industry does seem to love complexity and to abhor simplicity. The more complex the financial world is seen to be, the more managers, analysts, traders, consultants, regulators, and risk managers feel they add value and expect to be paid. But there is a lot of benefit to the ultimate buyers of financial services and products to keep things simple.

Nonetheless, packaging up increasingly complex strategies, trading tools and risk premia seems to be the general direction of travel right now.

And if it does play out this way it’s going to be pretty disruptive both for the investment industry and financial markets. We’ll certainly have more SNAFUs like $XIV (RIP).

Comments