China’s robot revolution

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The Ying Ao sink foundry in southern China’s Guangdong province does not look like a factory of the future. The sign over the entrance is faded; inside, the floor is greasy with patches of mud, and a thick metal dust — the by-product of the stainless-steel polishing process — clogs the air. As workers haul trolleys across the factory floor, the cavernous, shed-like building reverberates with a loud clanging.

Guangdong is the growth engine of China’s manufacturing industry, generating $615bn in exports last year — more than a quarter of the country’s total. In this part of the province, the standard wage for workers is about Rmb4,000 ($600) per month. Ying Ao, which manufactures sinks destined for the kitchens of Europe and the US, has to pay double that, according to deputy manager Chen Conghan, because conditions in the factory are so unpleasant. So, four years ago, the company started buying machines to replace the ever more costly humans.

Nine robots now do the job of 140 full-time workers. Robotic arms pick up sinks from a pile, buff them until they gleam and then deposit them on a self-driving trolley that takes them to a computer-linked camera for a final quality check.

The company, which exports 1,500 sinks a day, spent more than $3m on the robots. “These machines are cheaper, more precise and more reliable than people,” says Chen. “I’ve never had a whole batch ruined by robots. I look forward to replacing more humans in future,” he adds, with a wry smile.

Across the manufacturing belt that hugs China’s southern coastline, thousands of factories like Chen’s are turning to automation in a government-backed, robot-driven industrial revolution the likes of which the world has never seen. Since 2013, China has bought more industrial robots each year than any other country, including high-tech manufacturing giants such as Germany, Japan and South Korea. By the end of this year, China will overtake Japan to be the world’s biggest operator of industrial robots, according to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR), an industry lobby group. The pace of disruption in China is “unique in the history of robots,” says Gudrun Litzenberger, general secretary of the IFR, which is based in Germany, home to some of the world’s leading industrial-robot makers.

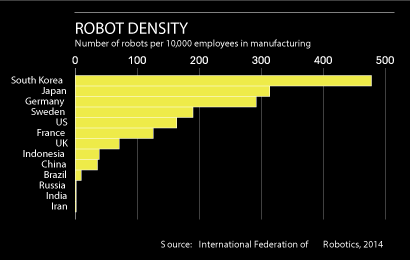

China’s technological transformation still has far to go — the country has just 36 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers, compared with 292 in Germany, 314 in Japan and 478 in South Korea. But it is already changing the face of the global manufacturing industry. In the process, it is raising broader questions: can emerging economies still hope to follow the traditional route to prosperity that the developed world has relied upon since Britain’s industrial revolution in the 18th century? Or will robots assume many of the jobs that once pulled hundreds of millions out of poverty?

. . .

China’s spending splurge on industrial robots has its roots in a pressing economic problem. From the 1980s onwards, as Beijing’s Communist rulers opened up to global trade, the country’s huge, cheap workforce helped make it the world’s biggest exporter of manufactured goods. Breakneck economic growth lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty and transformed swaths of the country, as workers migrated from the countryside to the city. But a growing middle class and an ageing population have led to rising wages, eroding China’s competitive advantage. Partly because of the one-child policy, formally phased out in 2015, China’s working-age population is expected to fall from one billion people last year to 960 million in 2030, and 800 million by 2050.

In recent years, China’s central planners have been promoting automation as a way to fill the labour gap. They have promised generous subsidies — to be doled out by local governments — to smooth the way for Chinese companies both to use and build robots. In 2014, President Xi Jinping called for a “robot revolution” that would transform first China, and then the world. “Our country will be the biggest market for robots,” he said in a speech to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, “but can our technology and manufacturing capacity cope with the competition? Not only do we need to upgrade our robots, we also need to capture markets in many places.”

The march of the machines, not just in China but around the world, has been accelerated by sharp falls in the price of industrial robots and a steady increase in their capabilities. Boston Consulting Group, a management consultancy, predicts that the price of industrial robots and their enabling software will drop by 20 per cent over the next decade, while their performance will improve by 5 per cent each year.

Liu Hui, an entrepreneur in his forties, is making the most of China’s robot boom. In 2001, when he opened his first factory in Foshan, an industrial city of seven million people in Guangdong, he started out making knock-offs of electric fans. As his business grew, he moved to bona fide manufacturing, producing components for Chinese home appliance brands. Then, in 2012, spotting an opportunity in a growing market, he jumped into the emerging world of robotics. Liu now imports robotic arms from suppliers such as the Swedish-Swiss conglomerate ABB, and sells them on to Chinese manufacturers, helping them integrate the machines into their production lines. It is a highly specialised business. Most of his customers are component-makers who supply motors and other parts to large Chinese home-appliance brands such as Midea and Galanz, which produce air conditioners, refrigerators and more.

Business has expanded so quickly in the past year that Liu does not have enough space in his factory for all the machinery he is assembling. He has to store parts designed to support a $23,000 ABB robot under a makeshift lean-to outside. “Things are changing rapidly,” he says. “The cost of labour is rising every year, and young people don’t want to work on the production line like their parents did, so we need machines to replace them.”

The stereotypical image of China’s factories can still be found in many places: tens of thousands of people in long lines hunched over sewing machines or slotting components into a printed circuit board. But that mode of manufacturing is starting to be replaced by a more mixed picture: partially automated production lines, with human workers interspersed at a few key points.

Meanwhile, China is developing its own robot makers. In September last year, Ningbo Techmation, a Shanghai-listed producer of machinery for the plastics industry, launched a subsidiary, E-Deodar, making robots that are 20-30 per cent cheaper than those produced by international companies such as ABB, Germany’s Kuka or Japan’s Kawasaki. The E-Deodar factory in Foshan, with its café, chill-out zone and open-plan production line, looks more like the offices of a Silicon Valley tech start-up than a Chinese industrial workhorse. “Our global rivals are very good at making robots but their costs are higher and they are not so good at understanding the needs of local customers,” says Zhang Honglei, the company’s 35-year-old, spiky-haired technical director.

This year, Zhang plans to produce 350 distinctively green-coloured robots, which are designed for use in plastic factories and sell for between $14,000 and $18,000 each; in three years’ time he hopes to produce 3,000 a year. “We have to move fast because automation is a scale business,” he says. “The bigger the better.”

Chinese manufacturers, which bought 66,000 of the 240,000 industrial robots sold globally last year, still largely prefer to buy international brands, according to Litzenberger of the IFR. But she expects that to change, particularly in the wake of the Beijing government throwing its full support behind the domestic robot industry in recent years. “They are developing very fast,” she says.

At an imposing, colonnade-fronted government building — known locally as the “White House” — in the Shunde district of Foshan, officials are trying to put President Xi’s call for a robot revolution into practice. The province of Guangdong has vowed to invest $8bn between 2015 and 2017 on automation. Zhang Peng, vice-director of Shunde’s economy and technology bureau, recently had his office in the building reduced in size, in line with the Communist party’s call for bureaucratic austerity. But the budget for industrial automation was unaffected. Zhang says robots are vital to overcome labour shortages and help Chinese companies make better quality, more competitive products. Unusually straight-talking for a Chinese official, he warns: “If manufacturing companies don’t improve, they won’t be able to survive.”

————————-

Government support for the integration of ever cheaper and more efficient industrial robots is good news for factory owners in China, who are facing a weak global economy and a slowdown in domestic demand. But the benefits of the robot revolution will not be shared equally across the world. Developing countries from India to Indonesia and Egypt to Ethiopia have long hoped to follow the example of China, as well as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan before them: stimulating job creation and economic growth by moving agricultural workers into low-cost factories to make goods for export. Yet the rise of automation means that industrialisation is likely to generate significantly fewer jobs for the next generation of emerging economies. “Today’s low-income countries will not have the same possibility of achieving rapid growth by shifting workers from farms to higher-paying factory jobs,” researchers from the US investment bank Citi and the University of Oxford concluded in a recent report, The Future Is Not What It Used to Be, on the impact of technological change.

They argue that China’s rising labour costs are a “silver lining” for the country because they are driving technological advancement, in much the same way that an increase in wages in 18th-century Britain provided impetus to the world’s first industrial revolution. At the same time, according to Johanna Chua, an economist at Citi in Hong Kong, industrial laggards in parts of Asia and Africa face a “race against the machines” as they struggle to create sufficient manufacturing jobs before they are wiped out by the gathering robot army in China and beyond.

Tom Lembong, Indonesia’s 45-year-old trade minister, and a leading voice for liberalisation and reform within the government of Southeast Asia’s biggest economy, is aware of the risks. “Many people don’t realise we’re seeing a quantum leap in robotics,” he says. “It’s a huge concern and we need to acknowledge the looming threat of this new industrial revolution. But as a political and business elite, we’re still stuck on debates about industrialisation that were settled in the 20th and even 19th centuries.”

Countries such as Indonesia are already suffering from something that the Harvard economist Dani Rodrik has dubbed “premature de-industrialisation”. This describes a trend where emerging economies see their manufacturing sector begin to shrink long before the countries have reached income levels comparable to the developed world. Despite rapid economic growth over the past 15 years, Indonesia saw its manufacturing industry’s share of the economy peak in 2002. Analysts believe this is partly because of a failure to invest in infrastructure, and the country’s uncompetitive trade and investment policy, and partly due to globalisation.

Rodrik believes the country will never be able to grow at the kind of rapid rate experienced by China or South Korea. “Traditionally, manufacturing required very few skills and employed a lot of people,” he says. “Because of automation, the skills required have increased significantly and many fewer people are employed to run factories. What do you do with these extra workers? They won’t turn into IT entrepreneurs or entertainers; and, if they become restaurant workers, they will be paid much less than in a factory.”

The spread of robots makes it much harder for developing countries to get on the “escalator” of economic growth, he argues. That is bad news for the estimated two million young people who enter the workforce every year in Indonesia, a nation of 255 million, where 40 per cent live on $3 a day or less. Mahami Jaya Lumbanraja, a 22-year-old job-seeker on the Indonesian industrial island of Batam, is feeling the effects of the premature de-industrialisation phenomenon. For seven months he has been looking for a factory job in Batam, which sits just 20 miles from prosperous Singapore, but he has had no luck. Wearing faded jeans, a grey hoodie and an endearing smile, Lumbanraja says that although he has one year of experience working for Shimano, the Japanese manufacturer of bicycle gears and fishing tackle, he is not experienced enough to secure anything more than an entry-level position, and that there are many more job hunters than openings. “I can survive on the little money I get from busking and helping friends with construction work but I must get a proper factory job to save enough money so I can set up my own small shop later,” he says. Wages in Batam — around $230 per month — are double what Lumbanraja could earn in his home city of Medan, on the island of Sumatra. So he feels he must stay until he finds work.

Lumbanraja is one of about 700 Indonesians in their late teens and early twenties who visit the community centre at the Batamindo industrial park every day looking for work. In February, 3,000 people applied in person for just 80 positions at a Japanese-owned wiring factory there, a gathering so large that executives initially feared it was a labour protest.

Batamindo is a joint venture between Singaporean and Indonesian investors that was backed by Presidents Lee Kuan Yew and Suharto — the two nations’ respective rulers — when it opened in 1990. Intended as the showpiece of Indonesia’s industrialisation strategy, it has become a symbol of everything that is wrong with it. In recent times, an average of five factories a year have left the industrial park for other countries and the number of people employed there has dropped to just 46,000, from a peak of 80,000 in 2000. That is despite the fact that wages today are between one-third and one-half of the level paid in China’s Guangdong province.

Lembong, a Harvard graduate who ran his own Singapore-based private equity firm before he was appointed trade minister in August, says the government is determined to tackle the twin problems at the heart of Indonesia’s economic malaise: weak infrastructure and over-regulation.

But some argue that reform will come too late. During its period of rapid industrialisation, China invested in the modern highways, railways and ports necessary to support its manufacturing sector. In contrast, the physical infrastructure in Batam and much of Indonesia has “not changed much since the 1970s,” says Mook Sooi Wah, general manager of Batamindo.

Indonesia actually had a slightly higher “robot density” than China when the latest figures were collated by the International Federation of Robotics in 2014, although the situation is likely to have changed dramatically since then given the pace of Beijing’s automation push. This anomaly was largely the result of China’s manufacturing workforce being so much bigger than that of Indonesia, which still has no government plan or backing for industrial automation.

Indonesia’s regulatory process is as fusty as its infrastructure. Recently, legitimate shipments from a paper factory were held by customs at the Batam port because of a rule meant to stop the export of illegally sourced wood. These problems leave even Batam’s boosters exasperated.

Stefan Roll, a German manufacturing veteran who worked in China during its industrial take-off in the 1990s, enjoys living and working in Indonesia. But he worries that the country is missing its “golden opportunity” to become efficient enough to compete on a global scale. “When you are dealing with multinationals, time is money,” Roll says as he shows off his new factory in Batam, which assembles coffee machines for Nestlé. “But you can only do just-in-time manufacturing if you have good roads and infrastructure.”

While few doubt the depth of the challenges facing developing countries, not everyone sees the dilemma in such bleak terms. With wages in countries such as Indonesia and India much lower than in China and their populations still relatively young, some analysts believe they can attract more labour-intensive industries, such as garment-making, where widespread automation is not yet suitable.

“As China moves up the industrial chain, it’s actually freeing up a lot of opportunities for Southeast Asia and India,” says Anderson Chow, a robotics industry analyst at the investment bank HSBC, in Hong Kong.

Hal Sirkin, an expert on manufacturing at Boston Consulting Group, says that from the perspective of an economy such as India’s, it does not make sense to automate now because it would drive up the price of goods — “when they have one billion people who can make things cheaply”. He is among the tech optimists who believe that, in the medium term, automation will also create new business niches for emerging economies, mitigating the damage from the jobs that will be eradicated.

“We think you’re going to see more localisation rather than more scale,” says Sirkin. “I can put up a plant, change the software and manufacture all sorts of things, not in the hundreds of millions but runs of five million or 10 million units.”

But Carl Frey, an expert on employment and technology at the University of Oxford, warns that without better education and more skills, developing countries will struggle to take advantage of advancements in manufacturing.

“Technology is becoming increasingly skill-based,” he says. “Many of these countries don’t have a skilled workforce so they’re not very good at adopting these technologies.”

. . .

China itself is not immune from the negative consequences of automation. More than 40 per cent of its 1.4 billion population still live in the countryside, many in poverty, having benefited only marginally from the urban economic miracle.

But the government is betting that the benefits of promoting cutting-edge manufacturing will outweigh the damage from the potential jobs lost. The industrial strategy announced by Beijing last year — known as Made in China 2025 — is designed not only to improve the technological capability of its factories but also to support the development of Chinese brands internationally.

Chow, the HSBC analyst, says that as Chinese companies try to increase their exports to alleviate the impact of the domestic slowdown, they are likely to focus more on the quality of their products: “Quite often part of that development is a better production process, involving robotics.”

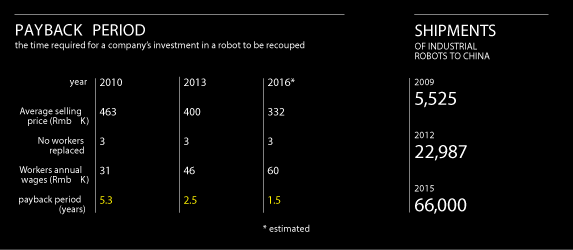

Every year, the amount of time it takes for a company’s investment in a robot to pay off — known as the “payback period” — is narrowing sharply, making it more attractive for small Chinese companies and workshops to invest in automation. The payback period for a welding robot in the Chinese automotive industry, for instance, dropped from 5.3 years to 1.7 years between 2010 and 2015, according to calculations by analysts at Citi. By 2017, the payback period is forecast to shrink to just 1.3 years.

Automation is not just about putting cheaper and more efficient robot arms on the production line. Li Gan, the general manager of Shangpin Home Collection, which makes and sells customised home furniture, says the greater opportunity is to integrate robots on the factory floor with real-time data from customers and automated logistics systems.

Thanks to the use of robots, the factory that Shangpin opened in Foshan in 2014 was 40 per cent more productive than its previous plant, even though it employs 20 per cent fewer people. Later this year, it will start up the machines at its newest and biggest production base, where it hopes to improve productivity fourfold with just double the number of staff, by using more robots to move supplies around the factory floor and help pack outbound shipping containers.

Drilling wooden slats for the company’s diverse range of beds, wardrobes and other bespoke furniture used to be a painstaking and sometimes dangerous process. Now a worker simply picks up each piece of wood, scans a barcode and puts the wood on a conveyor belt that takes it to the robot arm. The finished product returns on another belt. The process in between is strikingly complicated: Shangpin had to design a device to make sure that each slat would be aligned in the right way for it to be grasped by the robot arm, and the drilling specifications for the slats have to be pre-programmed and recorded in a barcode, because the robots do not yet have any artificial intelligence capability. Li Gan points out that human oversight and decision-making is still crucial. “Automation is just a technical process but what is more important is our thinking about how best to do this,” he says. “Every time we change something, we ask: is it more effective to do this using humans or robots?”

Boston Consulting Group forecasts that the percentage of tasks handled by advanced robots will rise from 8 per cent today to 26 per cent by the end of the decade, driven by China, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the US, which together will account for 80 per cent of robot purchases. Sirkin at BCG says that the rapid expansion of automation could be compared to the difference between the “human learning curve” and Moore’s Law, which posited that computing power could double every 18 months to two years. “Even if you’re very good, humans can only double their productivity at best every 10 years,” he says. In contrast, researchers can push robots to double their productivity every four years, he estimates. “Compounded over time, that makes a big difference.”

As China and other industrial leaders build more and better robots, the tasks they can take on will expand. Butchery, for example, was long considered the sort of skill that machines would struggle to develop, because of the need for careful hand-eye co-ordination and the manipulation of non-uniform slabs of meat. But Sirkin has watched robots cut the fat off meat much more efficiently than humans, thanks to the use of cheaper and more responsive sensors. “It’s becoming economically feasible to use machines to do this because you save another 3 or 4 per cent of the meat — and that’s worth a lot on a production line, where you can move quickly.

“There are things that humans can do better than robots,” he adds. “But they are getting less and less.”

Ben Bland is the FT’s South China correspondent and a former Indonesia correspondent

Photographs by Zeng Han and Muhammad Fadli

A brief guide to industrial robots

What is an industrial robot?

Many automated tasks in factories are performed by robotic arms programmed to complete repetitive and sometimes dangerous tasks.

A growing number of factories are also buying self-driving freight carriers and autonomous forklift trucks to reduce manpower.

Most industrial robots operate at a distance from their co-workers, sometimes in cages for safety reasons, but a new generation of humanoid robots is being developed to work alongside humans.

The $25,000 Baxter robot, for instance, which is designed to perform simple tasks such as packing and loading, has a screen with an animated face that frowns when there is a problem.

What can they do well?

Three-quarters of all industrial robots operate in four sectors: computers and electronic goods; home appliances and components; transportation equipment; and machinery. That’s partly because automation makes financial sense in these industries and partly because of the limited nature of the existing technology.

Industrial robots are usually fixed in a single location and are adept at performing uniform tasks with objects that are stationary or that move at a predictable speed.

Robots can work more quickly than humans, with a high degree of consistency and precision, and do not need breaks to sleep or eat, of course.

What can’t they do well?

Other than a few cutting-edge “intelligent” robots, most of these machines have to be pre-programmed for each specific task on the production line.

Precision can be a challenge too. Robots have no problem placing electronic components on to a flat circuit board, for instance, but struggle to assemble a car battery, which has many small parts that must be installed at odd angles.

Very labour-intensive tasks such as sewing garments and shoemaking have seen minimal automation so far. But that is starting to change, with Adidas opening a robot-dominated shoe factory in Germany this year.

Letter in response to this report

Labour and leisure strategies for the robot revolution / From Ira Sohn

Comments