History is better served by putting the Men in Stone in museums

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is an FT contributing editor

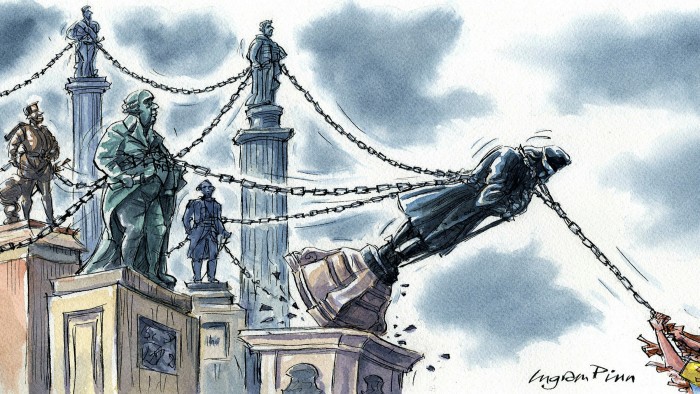

Statues are not history; rather, its opposite. History is argument; statues brook none. The whole honour of history lies in its contrarian irrepressibility; its brief to puncture the pieties of power, should they belie the truth. Those horrified by the de-pedestalisations of recent days — the Black Lives Matter protests have led to the felling of statues from the slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol to the brutal colonialist Leopold II in Belgian cities — claim that such acts “erase” history. But the contrary is true. It is more usually statues, lording it over civic space, which shut off debate through their invitation to reverence.

It’s often only when statues are threatened that they are noticed. How many visitors to the London Docklands Museum paused before the portly statue, taken down on Tuesday, of Robert Milligan, owner of 526 humans, to launch a discussion over the indispensability of slavery to the mercantile fortunes of West India Dock? How many American Rhodes scholars are aware that the benefaction which paid for them to study at Oxford was the expression of Cecil Rhodes’s mission to reverse independence; that their presence in the university was part of his plan to reunite America with Britain, thus sealing the imperial supremacy of the white Anglo-Saxon race?

Most statuary is self-defeating by virtue of its obligations to dignity and flattery. Aspiring to convey immortality, it ends up delivering stony lifelessness. The exceptions are those which rely on foreknowledge of tragic endings. The spell cast by the 19-foot-tall seated Abraham Lincoln in Washington depends not only on knowledge of his murder but also on the eloquence of the Gettysburg Address engraved on the memorial’s walls. Lincoln is enthroned, but the president’s majesty is that of the incarnation of the sovereignty of the people, that word thrice repeated, like a tolling bell, in the speech’s closing sentence.

For all its pretensions to perpetuity, statuary is vulnerable to unpredictable shifts in public opinion. We speak of the toppling of tyrants precisely because our mind’s eye sees the tumbling of their statues: surrogate dismemberment acted out on their sculpted alter egos. When the statue of Feliks Dzerzhinsky in Moscow was taken down in 1991, it was the acme of optimism about Russia’s redemption into freedom. The founder of the Soviet Cheka (later the KGB) had adamantly gazed over Lubyanka Square in Moscow, the headquarters of the secret police as well as their prison. Unsurprisingly, the most powerful veteran of the KGB, Russian president Vladimir Putin, has since made noises about restoring the statue.

But then statues are revelations — not about the historical figures they represent, but about the mindset of those who commissioned them. The equestrian statue of Charles I standing at the top of Whitehall was made for the private garden of the Lord High Treasurer. Come the civil war, a hunt went on to secure the statue so that any royalist mischief would be pre-empted by its destruction. Hidden in Covent Garden, it was sold at the Restoration by its concealer for a hefty sum so that Charles II could re-erect it a few hundred yards from the site of his father’s beheading. At the other end of Whitehall, Oliver Cromwell, designed for the tercentenary of his birth in 1899, ran into opposition from Irish Home Rule MPs. The Liberals, out of power and eager to bring the evangelical vote back to the fold, allied with Unionists to promote the statue. Lord Rosebery, whose anonymous funding made it happen, stretched history by claiming Cromwell as the bringer of toleration to England. And there he stands, wartless, Bible in one hand, sword in the other, before the parliament whose sovereignty he was never shy of brushing aside.

It’s to be expected, then, that the dramatic and belated change in attitudes towards racial injustice we are now witnessing will have an effect on who can be considered tolerable and who intolerable to memorialise. In Virginia, the statue of Robert E Lee will be removed from its site in Richmond, the erstwhile capital of the Confederacy. Lee, whose myth of Christian gallantry is at the heart of “Lost Cause” historiography, was an especially brutal slave owner, given to brining the lashes laid on the backs of runaways. Wading into a controversy to rename military forts bearing the names of Confederate officers, President Donald Trump has vowed to resist the move, claiming they have been integral to America’s history of “Winning, Victory and Freedom”. This last would have been a surprise to the enslaved, whose perpetuated servitude was the true cause of the South.

Let them disappear, then, but not into canals, ponds or rubbish dumps, since arbitrary acts of destruction shut down debate quite as much as uncritical reverence. Better, surely, to relocate them to museums where, properly curated, they can trigger genuine debate and historical education. One thing that the pandemic caesura has wrought is a confrontation with big historical matters: who are we as a nation, what we have been, and where we are going? If the Men in Stone (and they are overwhelmingly men) can deepen that understanding they will have served their purpose better than ever they did up on their pigeon-stained plinths.

Letters in response to this column:

Yorkshire Sculpture Park could provide the model / From Reverend Toby Hole, Sheffield, Yorkshire, UK

Recalling a museum in Brunel’s railway station / From Kate Nottage, Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire, UK

Comments