Tunisia: Pointing ahead

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Between the ages of 86 and 88, Beji Caid Sebsi founded a political party, won two elections, including one for the presidency, and established himself as Tunisia’s most powerful politician. Four years on from the revolution that convulsed his country and ignited the Arab awakening, the veteran bureaucrat is plotting his next move.

Tunisia is a relative oasis in a dangerous neighbourhood, the only democratic survivor of the 2011 popular uprisings. Libya, Yemen and Syria, as well as Iraq, remain rent by ethnic and religious strife, stoked by radical Islamic groups exploiting the power vacuum left by the toppled autocrats.

The small North African state stands out because its political leaders opted for that rare Arab commodity — compromise. Nahda, its own Islamist party, relinquished power under popular pressure and respected the result of elections. The transition is still fragile but Tunisia offers a sliver of hope that western-style democracy and Islamism can coexist peacefully in an Arab state on the Southern Mediterranean shore.

“Tunisia is a civilisation that dates back 3,000 years — we had a state back then. Throughout history and ever since the days of Carthage, it was one of the first countries to have a constitution,” says Mr Sebsi sitting inside an elegant 1960s presidential palace in Carthage. “We’re also a country of the ‘juste milieu’ — we never go to extremes. And every time we drift towards the extreme we go back to dialogue. That is Tunisia.”

The calm, soft-spoken Mr Sebsi emerged after the revolution as a reassuring father figure who reminded Tunisians of the days of the late Habib Bourguiba, the resolutely secular founder of modern Tunisia, whose portrait, as a dashing young man, hangs in the presidential office.

Faced with the rapid rise of Nahda after the revolution, Mr Sebsi gathered around him various anti-Islamist forces, some leftists, some from the previous regime, and many women, into Nidaa Tunis, a liberal party. There are plenty of sceptics who worry that Nidaa is nothing more than a new face to the old autocratic ruling party. The president insists Tunisia will never go back to the past. “There is no risk at all,” says Mr Sebsi. “These concerns are unfounded.”

Troubled neighbourhood

In 2013, Tunisia was paralysed by strikes and undermined by insecurity. Jihadis released from jail began to organise and, aided by the chaos next door in Libya, networks of recruitment for the civil war in Syria were thriving. And fledgling political parties — still savouring the freedom from the corrupt and thuggish autocrat Zein al-Abidine Ben Ali — were at each other’s throats.

But unlike its unruly neighbours, the Sunni Arab North African country (population 11m) was small enough and religiously homogenous enough to hold together. In contrast to Egypt, where a strong army has provided the backbone for authoritarian regimes, Tunisia was blessed with a broad middle class and a powerful union movement, but above all a small group of politicians with a deep sense of national responsibility.

When Tunisians stared into the abyss between 2012 and 2013, a trade union-sponsored national dialogue helped both the Islamists and Mr Sebsi’s camp to pull back. There was plenty of bad blood between him and his Islamist counterpart, Rachid Ghannouchi, but these “best of enemies” have found a way to work with each other. “We are not allies,” says Mr Sebsi, while acknowledging that a measure of mutual trust is a “necessity”.

On Avenue Habib Bourguiba in downtown Tunis, where the largest rallies against Mr Ben Ali were held in 2011, the streets were packed last week with crowds celebrating the fourth anniversary of the revolution. Islamists and secular leftists marched in separate groups, chanting slogans amid a din of klaxons and nationalist music. Occasionally heated exchanges broke out, a sign of the underlying polarisation in the country.

With the transition completed, the question is whether Mr Sebsi’s Nidaa Tunis party will form a government of national unity with the Islamists. The president has already appointed a technocratic, independent prime minister, Habib Essid, that Nahda has backed.

The Islamists, runner-up in the elections, seem interested in a coalition with Nidaa but the president is non-committal. “People who voted for us are against the inclusion of Nahda [in government],” he says.

A unity government would ostensibly maintain the consensus and rally parties around an ambitious economic reform programme. Unemployment, poverty, strained public finances and a lack of domestic and foreign investment leave the government with little room for manoeuvre. For all the political progress, including a model constitution, economic problems have piled up, and Tunisia has received meagre financial support, both from Europe and the richer Arab states in the Gulf.

Mr Sebsi complains that very little of the funds promised at the G8’s 2011 summit in Deauville materialised, suggesting that the election of an Islamist party to power after the summit discouraged international support. “I hope now they [the world community] no longer have any excuse.”

No time to waste

The budget has ballooned as successive governments — there have been five since 2011 — have responded to industrial unrest with fourfold salary rises and the absorption of some of the unemployed into a bloated public sector. Government debt has risen from 32 per cent of gross domestic product to 50 per cent.

Meanwhile, the informal economy, notably smuggling, has expanded to the point where it represents 40 per cent of the economy according to local business people. “No one is counting the cost of the revolution,” says Fadhel Abdelkafi, head of Tunisie Valeurs, an investment firm. “It is serious.”

Businesses fear that the more inclusive the government, the less decisive it will be. Asked whether she favours a national unity government, Ouided Bouchamaoui, the feisty head of the Tunisian confederation of private employers, delivers an emphatic “No”. In her view, Tunisia needs a government “with the authority to decide and the programme to defend”.

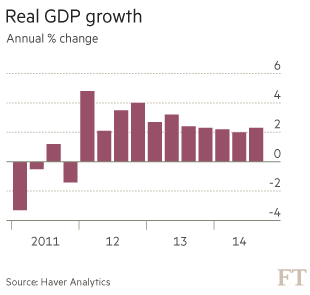

Tunisia has no time to waste. For the past year, a technocratic government has laboured to rein in spending. The budget deficit last year was projected at 6 per cent of GDP but came in better than expected at 4.9 per cent. The current account deficit, 8 per cent of GDP, is more troubling. But the country is deeply dependent on European markets that are grappling with slow growth and deflation. Full year growth in Tunisia is expected to fall short of 3 per cent in 2014, below pre-revolution years and nowhere near the rates of 7-8 per cent that would give the country a chance of creating enough jobs to satisfy the disaffected youth who sparked the uprising.

Analysts and bankers speak, in fact, of two Tunisias: one is productive and concentrated in the coastal areas; the other lies in the interior, where the revolution started, and the badlands of the south, where smuggling is rife. Some estimates suggest that as many as 1m Tunisians are living exclusively off smuggling of everything from subsidised energy to food products.

“The social situation is catastrophic,” says Michael Ayari, Tunisia analyst for the International Crisis Group. He argues that while tensions between Islamists and non-Islamists have dominated the political debate, the more worrying fissures are the disparities between the regions, with the neglected parts of the country even more frustrated today because they largely voted for Mr Sebsi’s opponent in the presidential elections.

Jihadis’ appeal

On the outskirts of the capital, in Hay Tadamoun, a poor, overpopulated neighbourhood that played a leading role in the revolution, the cafés are full of surly unemployed young men drinking tea and smoking shisha. None of them voted in the elections and none expressed any confidence in Nahda or Mr Sebsi’s Nidaa Tunis.

“We were better off under Ben Ali,” says one wild-eyed 20-something. “You might as well bring him back.”

Such neighbourhoods are fertile ground for the recruitment of jihadis — one of the most daunting problems facing the Sebsi administration . Despite a successful political transition, Tunisia has provided the largest contingent of fighters — some 3,000 recruits — to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis), which controls parts of Syria and Iraq. “Why not join Daesh [the Arabic name for Isis]. At least it is fighting for something, for Islam,” says one young man at the café. Another says recruiters pay between $1,000 and $3,000 to prospective fighters, an appealing sum for the unemployed.

Olfa Lamloum, Tunisia manager for International Alert, a non-governmental organisation that has studied areas such as Hay Tadamoun, says it is disillusionment and a lack of hope that drives the youth to leave. Some try to make their way to Europe, via Lampedusa in Italy, while others succumb to the appeal of radical preachers and end up in Syria, often becoming radicalised in a matter of months.

Ansar al-Sharia, the radical group that at one time said violent jihad should not be practised inside Tunisia, has changed its tune since being outlawed in 2013. This raises concerns of blowback when Tunisians fighting in Syria return home. One jihadi accused of political assassinations in Tunisia is believed to have been linked to the two Kouachi brothers responsible for the massacre at the satirical French newspaper Charlie Hebdo earlier this month.

While the government of Nahda took too long to crack down on radical Islamists, Mr Sebsi is determined to consolidate progress made over the past year — so much so that some analysts fear a return of the heavy hand of the state.

The president says security forces are now on the offensive and expresses concerns about the threat posed by the return of jihadis from Syria. He believes that the struggle against terrorism cannot be waged solely through security measures.

“You need social policies that address the root causes of terrorism, I know it’s an international phenomenon but the involvement of Tunisians in it is also related to the economic situation,” he says. “We have to think of a global strategy for the whole region and Europe is not protected either.”

Business groups say the only way to address social ills is to accelerate growth and attract foreign investment. This, however, also requires the government to implement reforms, including in the tax and subsidies regimes, privatisations and, crucially, to pass a new streamlined investment code. “Why is the investment code 1,000 pages? It should be a single page,” says Mr Abdelkafi. “The Tunisian administration is not here to attract investments,” he complains.

Hakim Ben Hammouda, economy and finance minister in the outgoing government, says that with the macroeconomic situation stabilised, the launch of big infrastructure projects in which the private sector invests should be a priority to absorb jobless youth.

“Since 2011 we’ve been managing the chaos, the emergency situation, and the security and political crisis. Now you need to give hope,” he says. “You need to say what Tunisia will look like in 2030 and convince people that the end of authoritarian rule is a starting point to a new social and economic era. That’s the missing part of the Tunisia story.”

***

Power broker: Trade union happy to play ‘regulator’ to politicians

The central part played by the general trade union in Tunisia’s uprising is one of the untold stories of the 2011 revolution. After street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself alight in Sidi Bouzid and sparked a wave of youth protests, local chapters of the trade union rebelled against the pro-regime leadership to join the revolt.

Since the toppling of Zein al-Abidine Ben Ali, the UGTT (the French-language acronym for the Tunisian General Labour Union), has again emerged as the country’s most important power broker, helping to bridge the gap between Islamist and anti-Islamist camps.

Hassine Abassi, the trade union chief, is a small man with an intense stare. He is well aware of his power. “It is a difficult equation to play a national role to reconcile between different stakeholders and preserve the social and economic interests of your members . . . Rarely do you have trade unions playing both roles,” he says. “But it’s not a strange mandate for the UGTT.”

Farhat Hached, the late head of the union, played a lead role in Tunisia’s fight against French colonialism, but was assassinated in 1952, four years before the country won its independence. “The liberation legacy is implanted in the minds of the trade union leaders and we’ve played a similar role on different occasions,” says Mr Abassi.

The UGTT, he says, is now acting as a “regulator” of the political scene. Its role, however, is provoking anxiety in the business community, which worries that the union’s oversized authority, and the pressure for wage hikes, could hinder economic liberalisation. Mr Abassi says he backs reforms, but only as part of a new development model that shifts attention to underprivileged regions and the needs of the unemployed.

“The revolution erupted . . . because of an unfair development model and

a lack of fair distribution of wealth between regions and sectors,” he says.

Today, he says, only workers are paying taxes, while the informal economy thrives and capital flees the country. “We back fundamental and comprehensive reform,” he says.

Comments