The answer to improved community healthcare? Capacity building

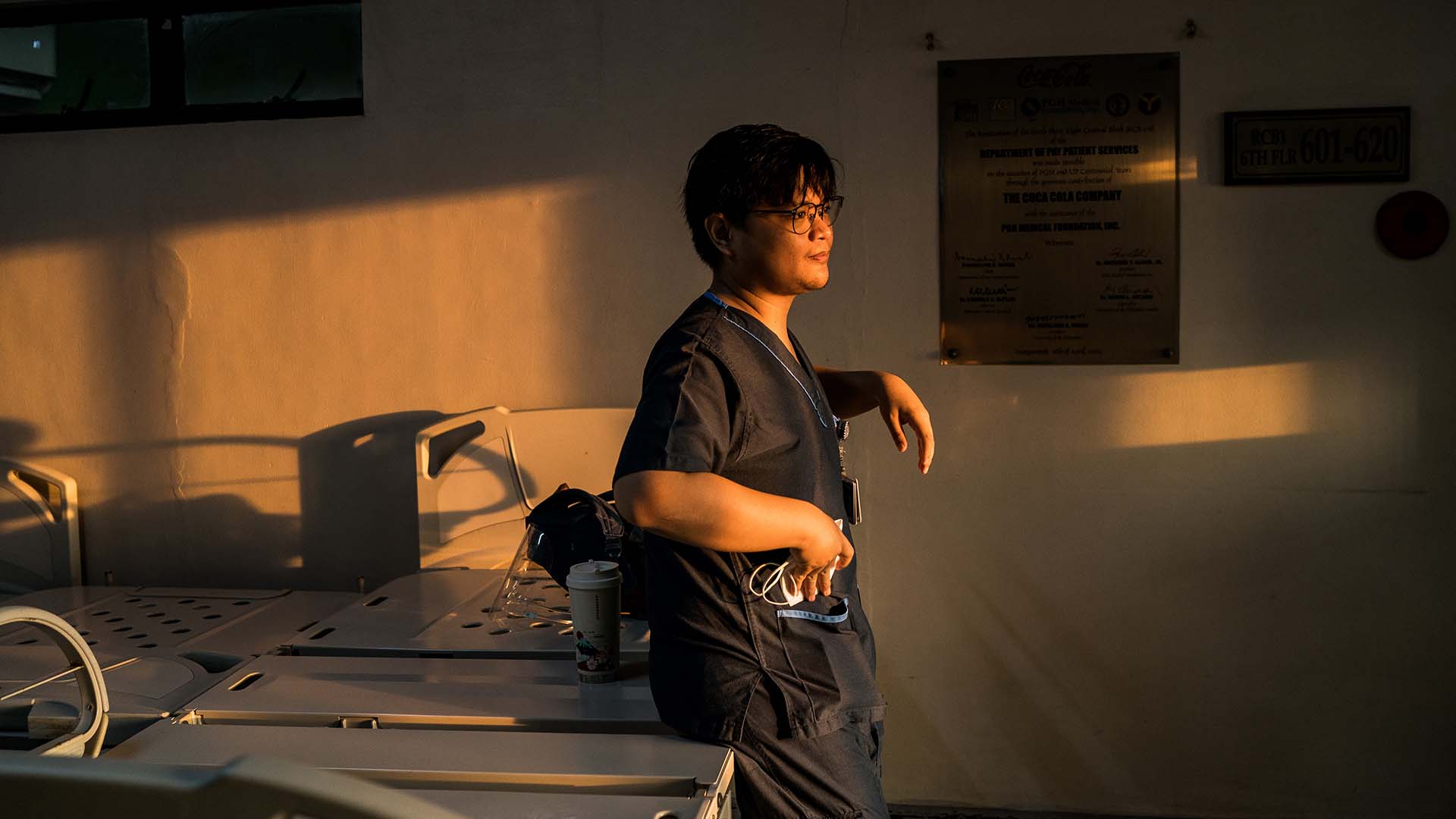

Community health workers act as a vital human link between public health systems and patients the world over. How could this cadre of caring hands be made even more powerful and effective?

Community health workers (CHWs) play an important role in bridging the gap between public health systems and the wider communities that they serve around the world, helping to provide critical services such as immunisation programmes and pre- and post-natal care.

One such CHW is mother of three Kola Lakshmi, who lives in Penjerla, a village near the city of Hyderabad, southern India’s tech powerhouse. Lakshmi is proud to call herself an Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA), a role introduced by the Indian government in 2005 to serve the needs of rural communities as part of its National Rural Health Mission (NRHM).

Lakshmi was hired in 2006 following a conversation between the head of her village and the district

health supervisor, who identified the need for a female CHW who could work to improve maternal health

and the delivery of childhood immunisations locally.

The breadth of Lakshmi’s responsibilities not only underlines the critical public health role that ASHAs play but also the importance of ensuring that ASHAs and other CHWs are well trained to provide a range of health services that their communities need and increasingly expect. This is especially the case in rural communities where 69 per cent of India’s population resides and access to healthcare is limited.

While the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends CHWs everywhere receive ongoing

training to maximise their potential impact, there is no commonly held view of how this is best

delivered or how success might be measured. Surveys of approaches to

training around the globe have shown that in-person mentoring tends to be favoured over mobile

technologies, despite the prevalence of mobile phone usage across Africa and India, for example.

In 2018, to promote a preferred approach to CHW training, the WHO published a series of recommendations which included using e-learning, face-to-face learning

and community-based training to teach: interpersonal skills; an understanding of health promotion and

disease prevention; data collection; personal safety; and a balance of medical theory and hands-on

practical skills. It also recommended competency-based formal health qualifications for further career

progression where appropriate.

Lakshmi herself received one month’s basic training when she first started her work as an ASHA,

followed by a week’s refresher course in 2012, 2013 and 2016, as well as hands-on training with

more experienced medical personnel. Adequate supervision and mentoring is another WHO recommendation for

practising CHWs.

Today, Lakshmi is a well-respected member of her village who

liaises with other health officials, teachers and community leaders. “The community calls

me ASHA amma [mother] and ASHA akka [older sister],” she says. “I visit 35 to 50

households per day on foot for antenatal visits.”

As an ASHA, Lakshmi has also been called upon to play a part in

India’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. This public health emergency has illustrated the

dynamic nature of CHWs’ work and the inherent need for continuous training and capacity

building to keep local skills in line with local needs. It also reveals the ways in which CHWs have

become more professional; as communities rely upon their services (as Penjerla village relies upon

Lakshmi), CHWs have had to become more adept at data management as well as monitoring non-communicable

conditions and preventing diseases such as malaria at community level.

Every week is a busy one for Lakshmi, as she explains: “On Monday, I make door-to-door

visits to meet pregnant and lactating mothers; on Tuesday, I discuss couples’ family planning;

Wednesday is immunisation day and Village Health Nutrition Day at the local health centre; Thursday is

usually for the school health programme but due to Covid-19 we are conducting a fever survey; Friday is

dry day in schools [to ensure that there is no standing water] to control vector-borne diseases [such as

dengue and malaria]; Saturday is scheduled for outreach immunisation and personal hygiene awareness in

targeted communities.”

The scope of her work shows both the need for specific medical training and the degree to which ASHAs

have become integrated into public healthcare systems. “I learnt the basics of maternal and child

health services,” says. “I also gained knowledge about general health issues, especially

related to common infections, and I am able to provide general medicines for the immediate relief of

minor illnesses such as fever and headaches.”

In an ideal world, Lakshmi says, she would

like more training to be delivered both in person and online; a view that shows the value of integrating

CHWs into designing training best suited to their own specific and individual needs. For example,

Lakshmi believes her mobile phone is a useful tool enabling her to communicate more effectively via

instant messaging platform WhatsApp, as well as allowing her to access more job-specific tools such as

the Covid-19 vaccination registration app.

“Technology is beneficial,” she says. “It has removed time delays in

communication and made it possible to do work without any interruptions.”

Lakshmi is

clearly passionate about her work and her thirst for training is rooted in her desire to do the best for

her community. What motivates her to complete her rounds day in, day out are the human interactions and

the sense of achievement that her work gives her. “The birth of a healthy baby makes [me]

joyful,” she says. “When I look at children in good health after vaccination, I feel

happy.”

As an ASHA working in a rural village, Lakshmi’s story illustrates the

willingness of CHWs to go the extra mile in the service of their communities – literally in the

case of home visits to deliver maternal care. The only ceiling in the value to their contribution is

perhaps continued investment and training that would enable CHWs to address the healthcare needs of

their communities.

Find out more about Johnson & Johnson

1 The World Health Organization. Community health workers: What do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. 2007

2 https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/4/e021467#ref-8

3 https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/4/e021467#ref-8

4 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275474/9789241550369-eng.pdf

5 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275474/9789241550369-eng.pdf

6 https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-021-00757-3#Sec24

7 https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-021-00757-3#Sec6