Delivering quality community-based healthcare, step-by-digital step

Community health workers are often under-equipped as they strive to deliver the best quality care, but in Kenya more than 3,000 government community health workers are using a mobile health app that assists with diagnoses and treatments while reducing infant and child mortality — it’s the kind of smart technology that could help transform essential healthcare in many developing countries

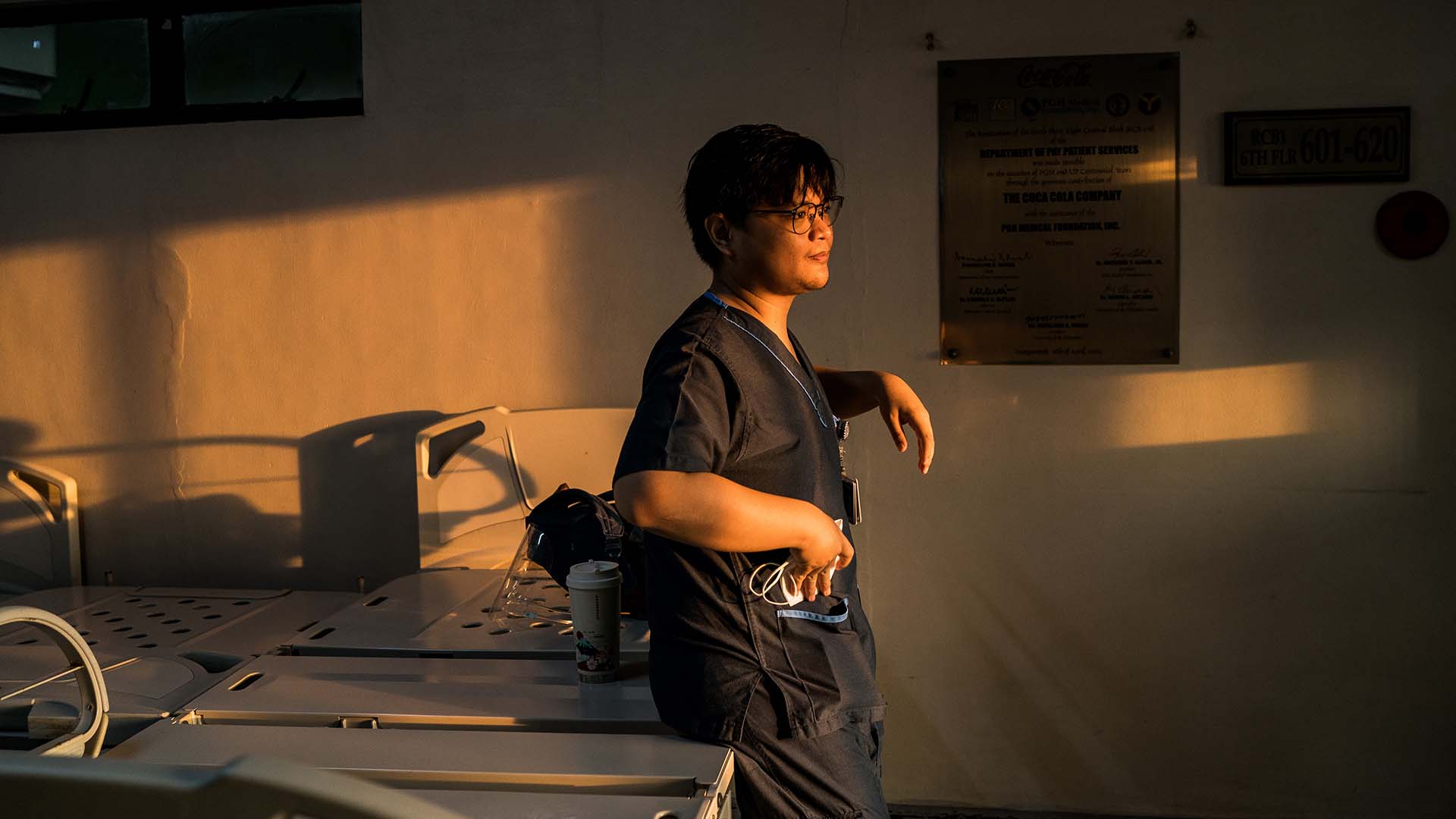

When she is asked what made her become a community health volunteer (CHV), as community health workers (CHW) are known in Kenya, Magdalene Espan remembers a tragedy she would rather forget. “A woman collapsed just near my house due to a postpartum complication,” says the 40-year-old single mother of four, who helps to provide essential primary healthcare to her local community in Kenya three days a week.

“We tried to get her to the main referral hospital in Isiolo town, but unfortunately she

haemorrhaged so much that she died before arrival,” she remembers. “I felt that if she had

received some support during and after her pregnancy, her death could have been avoided. That’s

when I decided I must volunteer to help save the lives of people who need similar support within my

community.”

Sadly, the story that Espan relates is not unusual and illustrates the desperate need for potentially

life-saving resources, especially in remote and hard-to-reach communities. CHWs play an essential role

in delivering healthcare in these settings, although they often operate with limited resources and often

need to travel long distances.

Alone and on foot, equipped with little more than an apron, minimal personal protective equipment,

and a first aid kit containing essential medication, Espan often walks 2km from her village, Busoro, to

the nearest health facility. She lives 11km from the nearest town and 3.5km from her nearest client.

Given this stark reality, there are inevitable limits on how many community members she can reach and

treat in person and whose health and treatment options she can monitor. And so, she mostly focuses on

providing care for the most vulnerable populations – pregnant women and young children under age

five. Nevertheless, Espan’s commitment to serving her community is impressive: she has mostly

worked as an unpaid CHV for 16 years and describes the role as requiring “a loving heart of

service”. Undeniably, it’s also a role of tremendous personal responsibility, the burden

of which is being eased thanks to innovative digital technology.

In Kenya, CHVs are the foundation of the country’s strategy for delivery of community health

services, which aims to provide basic prevention and care services such as the delivery of health

promotion messages, the treatment of common ailments and illnesses, and the establishment of protocols

for door-to-door delivery of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services.

Coached by government community health supervisors, CHVs operate within small geographical units with each CHV serving around 100 households. Even though CHVs have very limited resources and tools at their disposal, areas that have an active community health programme have been shown to benefit from improvements in antenatal care visits, testing and treatment for diseases such as pneumonia and malaria, and child immunisation. In 2019, Kenya had approximately 86,000 CHVs.

It’s clear that CHVs already play a vital role in the Kenyan health system, but with greater

investment, their impact could exponentially increase. Recently, Espan has been able to add technology

to her medical kit in the form of an app called Smart Health, which has been deployed to more than 3,000

CHVs by a non-profit, Living

Goods.

Operating with local agencies such as the Isiolo County Government, Living Goods aims to equip CHVs

not just with the technology, but with the tools, training, essential medicines, motivating compensation

and supportive supervision that will help to deliver the kind of prompt diagnosis and treatment that is

necessary to reduce infant mortality from malaria, diarrhoeal disease and pneumonia while educating

families about water, sanitation, proper nutrition and seeking care promptly when their children are

sick.

The open-source technology behind the Smart Health app that Espan now uses poses simple questions that aid the CHV in accurate diagnosis while also identifying acute cases for immediate referral to a local healthcare facility. It will also send daily text reminders to prompt the CHV to follow up periodically on treated or referred patients to ensure they complete the full course of their treatment and are receiving proper care.

Before the introduction of the app, Espan used manual registers to record her patients’

symptoms and case histories, a method that was cumbersome and prone to error, she explains.

“There was no standardised approach to doing things like assessments, which made us rely a lot

on memory,” Espan says. “[Through the app,] data is entered and reported in almost real

time, making it is easy to view your activity and performance in a given time period.”

The Kenyan government has recently embarked on an ambitious national community health digitisation

programme and is working with Living Goods and others to ensure that all CHVs in the country will be

equipped with digital tools to transform health service delivery and avail timely and reliable data for

decision-making. Well-applied digital technologies that are sensitive to local needs in communities

wherever they are in the world are a key part — but only a part — of a more holistic

approach to improving healthcare. In Kenya’s case, it will also mean working to improve the

recognition, renumeration and performance of CHVs, instituting policies and laws, and streamlining

public health commodity supply chains.

Espan is proud of the difference that she and her fellow

CHVs make to people’s lives, but she insists that more must be done to create a sustainable

healthcare system for the future. As she explains: “I hope to do even more.”