Emerging markets: The great unravelling

Simply sign up to the Currencies myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Faced with recession, decade- high inflation, a fiscal crisis and water rationing, more than 1m Brazilians took to the streets last month to protest against corruption and mismanagement in their government. In China, growth is slowing as property prices fall, propelling more than 1,000 iron ore mines toward financial collapse. The patriotic citizens of Russia, meanwhile, are deserting their nation’s banks, switching savings into US dollars.

Such snapshots of growing distress in the world’s largest emerging markets are echoed among many of their smaller counterparts. Several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa are beset by dwindling revenues and rising debts. Even the turbo-powered petroeconomies of the Gulf, hit by a halving in the price of oil over the past six months to $55 a barrel, are moving into a slower lane.

Though these expressions of distress derive from disparate sources, one big and insidious trend is working to forge a common destiny for almost all emerging markets .

The gush of global capital that flowed into their economies in the six years since the 2008-09 financial crisis is in most countries now either slowing to a trickle or reversing course to find a safer home back in developed economies.

Highest outflows since 2009

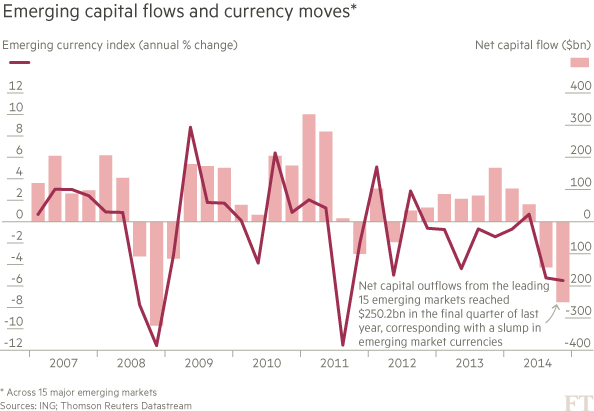

On an aggregate basis, the 15 largest emerging economies experienced their biggest absolute capital outflow since the crisis in the second half of last year, as a strong US dollar drove emerging market currencies into a swoon and investors grew nervous over the prospect of a tightening in US monetary policy, according to data compiled by ING. At the same time, low commodity prices slammed GDP growth rates across the developing world.

These trends, analysts say, signal a “great unravelling” of an emerging markets debt binge that has swollen to unprecedented dimensions. Importantly, the pain inflicted by this capital flight is being felt beyond financial markets in the real economies of vulnerable countries and in a surging number of emerging market corporations that are forecast to default on their debts.

“Certain parts of the world are looking really vulnerable,” says Maarten-Jan Bakkum, senior emerging market strategist at ING Investment Management. “Places like Brazil, Russia, Colombia and Malaysia, that rely heavily on commodity exports, are going to get hit even harder, while those countries that have borrowed most excessively like Thailand, China and Turkey also look risky.”

Analysts say that while emerging markets have been the setting for several recent financial squalls, the current exodus of capital could herald more fundamental changes. Indeed, although the “taper tantrum” of mid-2013 — triggered by the US Federal Reserve signalling its intention to unwind its monetary stimulus — caused turmoil in financial markets, its impact on real emerging market economies was transitory.

This time around, though, things look more serious. The International Monetary Fund said this week that total foreign currency reserves held by emerging markets in 2014 — a key indicator of capital flows — suffered their first annual decline since records began in 1995.

Without steady capital inflows, emerging market countries have less money to pay their debts, finance their deficits and spend on infrastructure and corporate expansion.

Real economic growth is set to suffer this year, analysts say. Capital Economics expects GDP growth in emerging markets to fall to 4 per cent from 4.5 per cent in 2014, as Russia slips deeper into recession, Brazil continues to struggle and China is hampered by its ailing property market.

Underlying such sober projections is a sense that an inflection point has been reached with the end of the commodity “supercycle” and the advent of low oil prices. “What is going on is a great unravelling of the market conditions of the past 15 years,” says Paul Hodges of International eChem, a chemicals and commodities consultancy.

Mr Bakkum also sees a significant reversal in the animating forces of global capitalism. “The EM capital outflows represent the gradual unwinding of the excessive inflows into the emerging world during the years of zero interest rates in the US,” he says.

However, the outlook is not universally bad. Investors have flocked to India, which has a reform-minded government and has gained from falling energy prices that have helped it slash its current account deficit. Indonesia and Mexico are also attracting investment for similar reasons.

Foreign exchange slump

Nevertheless, according to data collated by ING for the leading 15 emerging market economies, net capital outflows in the second half of last year totalled $392.4bn. This compared to a total of $545.9bn in capital outflows over three quarters during the 2008-09 crisis. If the first quarter of this year also shows a capital outflow, the total loss from emerging markets over three quarters could get close to that seen during the crisis. It is possible, analysts say, that outflows will not only continue in the first quarter of this year but may actually accelerate to eclipse the $250.2bn seen in the final three months of 2014.

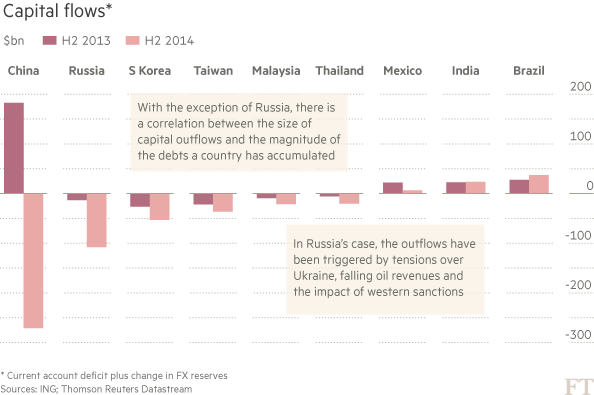

While in 2008-09 the US was a key catalyst of emerging market distress, this time China is seen as the chief bugbear. Slowing Chinese GDP growth, coupled with a slowdown in construction, is triggering a large bout of capital flight as investors think they will earn more by parking their money elsewhere.

The main expression of this reversal is the implosion of the “China carry trade”, in which Chinese investors borrowed at low rates of interest abroad to pump back into Chinese property and a range of shadowy financial products . But such investments now seem more risky, and a record $91bn fled the country in the final quarter of last year.

“It’s all China, directly and indirectly,” says Frederic Neumann, economist at HSBC. “Despite a solid current account surplus, capital outflows over the past six months have drained reserves from China’s vast forex chest . . . and with the renminbi more fairly valued today it is difficult to see China running big balance of payment surpluses again.”

In Brazil, fragility stems from a combination of falling commodity prices and the rising US dollar. Although the country managed to attract net capital inflows in the second half of last year, the cost of doing so was a punitive interest rate environment in which the policy lending rate is 12.75 per cent.

Paying debts

Like many emerging markets, critics say, Brazil failed to use its boom years to make the tough decisions needed to drive productivity growth. “To reform while you are facing headwinds is very difficult,” says Sergio Trigo Paz, head of EM debt at BlackRock. “Some emerging markets will struggle to keep their investment grade ratings.”

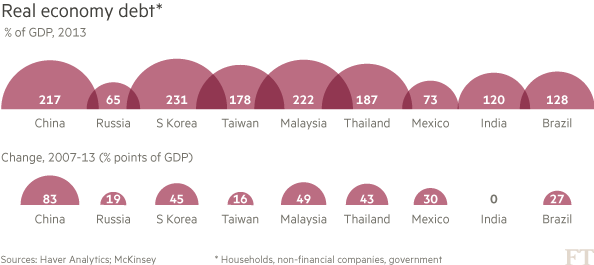

According to a study by McKinsey, total emerging market debt rose to $49tn at the end of 2013, accounting for 47 per cent of the growth in global debt since 2007. That is more than twice its share of debt growth between 2000 and 2007.

Some of the most significant capital outflows are originating from countries that piled debts up the quickest. South Korea, for instance, saw its debt to GDP ratio rise by 45 percentage points between 2007 and 2013, while China, Malaysia, Thailand and Taiwan experienced debt surges of 83, 49, 43, and 16 percentage points respectively.

But it is not only countries that are vulnerable. Another area of concern is the rise of the emerging market corporate hard currency bond market. Ten years ago, it hardly existed. Today, it is estimated at more than $2tn, making it bigger than the $1.6tn US high yield bond market, an asset class familiar to investors for decades. Its growth was fuelled by expansionary monetary policies in the US and elsewhere and by the hunt for yield among investors and fund managers with targets that could no longer be met in developed markets.

But US policy is changing course. David Spegel, head of emerging market bond strategy at BNP Paribas, is among those expecting conditions for emerging market borrowers to deteriorate. In a recent report, “Harbingers of Default”, he underlined the dangers posed by capital outflows: “The persistent higher cost of funding will continue to erode credit quality for related higher-risk issuers, if sustained . . . Since most defaults typically coincide with significant investor outflows, we continue to believe that further bouts of EM distress may yet come to bear on the market, as forced selling is exacerbated by already low liquidity conditions.”

Indeed, Mr Spegel notes, current bond prices suggest investors expect the rate of default for non-investment grade EM bonds — about a third of the total — to rise from 2.8 per cent on Wednesday to 12 per cent in January 2017.

If the upshot of all this is merely that countries and companies that have engorged themselves irresponsibly on debt are set to receive a dose of market discipline, then all well and good. The danger for emerging markets, and the wider world, is that the capital outflows will snowball to an extent that robs EM countries of the lifeblood they require to create jobs and engender their people with hope for the future.

Comments