Lunch with the FT: Travis Kalanick

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

An Uber car normally arrives in five minutes but I’ve already been waiting 10 for the company’s chief executive, Travis Kalanick. One of the joys of the driver-hailing app is watching the little car icon inch around its onscreen map towards your location, counting down the minutes. There are no reassurances of this kind about the whereabouts of my lunch partner, however, apart from an apologetic note from his handlers. Our venue, the Bluestem Brasserie in downtown San Francisco, was only selected that morning, out of convenience rather than any sentimental associations. Uber is all about instant gratification over forward planning, and “sentimental” is not a word usually associated with Kalanick, one of Silicon Valley’s most provocative street fighters.

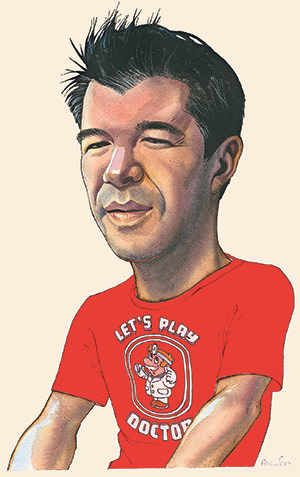

Arriving on foot from his offices just a block away, he tells me he hasn’t driven his own car in a year and largely travels by Uber these days – paying his own way despite running the company. Kalanick wears the dressed-down start-up uniform of zippered sweater, T-shirt, jeans and Nike trainers – minus the regulation hoodie. But at 37, with neat stubble and salt-and-pepper hair, he is a little older than the archetypal app developer and Uber is hardly a start-up.

In 2009, when Kalanick and his friend Garrett Camp came up with the idea of “pushing a button to get a ride”, it was, he says, a way for them to live like “ballers” – high-rolling sportsmen. Since then, Uber has rapidly evolved from a private, invitation-only limo service for a small group of friends into one of Silicon Valley’s hottest – and most controversial – companies. In December 2013, financial information leaked to the tech gossip blog Valleywag put Uber’s weekly income at more than $20m from more than 400,000 active “clients”; the company has not challenged the figures. Last year, it was valued at more than $3bn, with a $258m investment from Google Ventures and private equity firm TPG.

That injection of cash – huge, even in these frothy times on the US west coast – has helped Uber to double its footprint to 100 cities in the past six months. “We’re in four cities in China, five or six cities in India,” says Kalanick. “We’re in Bogotá and Cali in Colombia – everywhere.”

When I mention that a rival company, Lyft, is about to launch in 24 US cities, Kalanick is characteristically blunt. Most Silicon Valley executives would diplomatically say that the market is growing “crazy fast” and that there’s plenty of room for both of them. Not this one.

“We launched in 100 cities so they have to do something, and there’s a lot of places on that list I’m not sure I’d call a city – but they’ve got to do what they’ve got to do,” he says. “In the US, in many ways, the table is set. We’re 10 times bigger.”

So where next for Uber? Like any Silicon Valley entrepreneur worth their salt, Kalanick defers to the data. People sign up for the service even before it’s available in their city, he says, often from a phone that shares their location via GPS, so Uber sees every time they look, in vain, for a car. “We have 150,000 people who’ve opened the app in Miami: we have no operations in Miami.”

The waiter has yet to take our drinks order but already we’re veering into one of Kalanick’s biggest challenges: the taxi industry’s “war on Uber” and the regulations that frequently prevent “e-hailing” services from operating freely. Miami has proved to be one of Uber’s longest struggles against regulatory law but just the week before our lunch new fronts were opened in Berlin and Brussels.

In the latter, a city court order threatened to fine Uber drivers €10,000 if they were caught carrying private passengers because the company does not have the right licences. However, Neelie Kroes, the EU’s digital commissioner attacked the decision, which she said was “crazy” and “outrageous” and “about protecting a taxi cartel”, not consumers. Kalanick could not have put it better himself.

As the waiter arrives, I explain to Kalanick that our tab will be printed alongside the article. “That’s an interesting twist,” he smiles, perusing the long menu. “Let’s blow it out, man.” He duly orders a half-dozen oysters to share and a “French dip” steak sandwich with fries. I opt for “acorn-fed” pork belly “from the ranch”.

Despite photos on Twitter of him partying with rapper Snoop Dogg, Kalanick says he rarely goes out, or eats out, in San Francisco these days. Like most tech companies, Uber has a well-stocked staff canteen; others use food-delivery apps. In fact, some believe Uber might in the future outgrow taxis and swallow these kinds of delivery start-ups, to become a broader “on-demand” logistics business – an app as remote control for your life. It’s already trialling cycle couriers in Manhattan.

Amazon, once just an online bookstore, is often cited as a template for how Uber might develop. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and chief executive, is an Uber investor, though Kalanick rejects comparisons. “I think Uber is just very different, there’s no model to copy,” he says. “It may be the reason why we’ve been a lightning rod in so many ways, because we don’t do anything conventional . . . And then I think also, as an entrepreneur, I’m a bit of a lone wolf.”

His philosophy is to trust Uber’s employees to be “lone wolves” too. When launching in new cities, local teams enjoy considerable freedom to promote the service and recruit drivers as they see fit. This has led to entertaining stunts such as delivering tacos, ice-cream or even cuddly kittens “on demand” for a day.

Other tactics have been less cute: in January, Uber apologised after its New York team was busted for repeatedly calling and cancelling rides from a rival car service. Kalanick would not discuss the incident on the record but Uber admitted at the time that this method for getting drivers’ details, hoping to poach them, was “likely too aggressive a sales tactic”.

It was also fresh fodder for the company’s vocal critics. The “Who’s Driving You?” campaign, funded by the Taxicab, Limousine & Paratransit Association – the regulated portion of the US car transportation industry that has most to lose from the rise of such start-ups – routinely calls Uber “predatory”, “dangerous” and “irresponsible”. Boston’s police commissioner Bill Evans this year accused Uber of operating “gypsy cabs”.

To help his new recruits stay on the right side of the law, they attend a monthly session at what Kalanick calls “Uberversity”, where he explains “what we’re about, how we fight the good fight”. A lot of the questions he gets are about how to handle regulation, he says, something he calls “principled confrontation”.

He explains: “If you’re operating from strong principles, you can compromise when the person on the other side is operating from principles you respect,” he says. “When it’s about protecting incumbent industry, when it’s about providing less choices for citizens to get around the city, then there’s less to talk about.”

The oysters part of our order seems to have gone temporarily astray but the main courses have arrived and, between chomps of a giant steak sandwich, Kalanick details some of the barmier “protectionist schemes” to which Uber and its customers have been subjected, such as having to wait an hour after being called for a ride, sky-high minimum fares and drivers being sent back to a non-existent “garage” between jobs. In Paris, where drivers pay more than €200,000 to acquire one of the limited number of state taxi licences, disgruntled cabbies went one step further and slashed the tyres on Uber cars. But, Kalanick concludes, “Ultimately, progress and innovation win.”

….

Silicon Valley’s more wide-eyed start-up founders often pitch their ideas as “saving the world” – and genuinely believe that is what they’re doing, however mundane or minute the technical advances. Uber is more nakedly competitive and ambitious. “We feel we are very honest and authentic, to the point of being brutally honest,” Kalanick says with some understatement. “Not everyone likes that style, and I get that, but at least we’re trustworthy.”

Nonetheless, many city halls still aren’t sure how to handle Uber, a “marketplace” that owns no cars and employs no drivers – especially when, in 2012, it began to allow anyone with a car and a good driving record to be a makeshift taxi driver. Local authorities challenging this ride-sharing model are often encouraged by actual taxi drivers and their unions, who argue that Uber lacks the proper insurance and has been insufficiently thorough in its background checks.

Uber insists that its insurance is “best in class” and its driver checks “among the most stringent in the industry”. But its record on safety and liability will soon be tested in court. The parents of a six-year-old girl killed in an incident involving an Uber driver on New Year’s eve in San Francisco are suing the company. Uber has denied responsibility because the driver was not carrying a passenger at the time, which means its insurance was not applicable.

This is an extreme case, but Kalanick’s response to legal challenges has typically been hard-nosed; despite the rulings in Brussels and Berlin, the service continues to operate there, he proudly points out. He has earned his reputation as one of Silicon Valley’s most combative operators. “I’m a natural born trust-buster,” he says of his mission to smash the taxi cartels. “That’s probably the best way to put it.”

That’s not what many would call Kalanick. He’s more often styled as an ultra-capitalist, not least because of “surge pricing”, where Uber doubles or triples fares during busy periods such as rush hour or in bad weather. He says this is to encourage more drivers on the road when they are needed, not just to milk desperate passengers. But the free-market practice has attracted high-profile criticism. On Twitter, Salman Rushdie described surge pricing as a “cynical rip-off”.

Kalanick didn’t help his case by choosing the cover of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, a favourite of laisser-faire capitalists, as his Twitter profile picture. He thinks it’s an “awesome book” but takes issue with the way the press latched on to the association: “All of a sudden, I’m a raging objectivist, or whatever it is.”

He has now replaced Rand with Alexander Hamilton, one of America’s founding fathers, who died in a duel. He admires the founding fathers, because “they have to hustle, just like an entrepreneur, because they’re creating a country. Whoa, how cool is that?”

Could he see himself in politics one day? “It’s definitely not for me,” he says, adding that he is “not diplomatic enough”. Yet, surprisingly, he likens Uber’s city managers to local mayors. “There’s an old-school ‘pillar of the community’ thing that happens when you roll out a transportation system for a city.” It’s an odd choice of words, given that Uber’s legal arguments often rest on classifying itself as an asset-light software company, not as a transportation provider.

….

Kalanick removes his sweater to reveal a red T-shirt with a Super Mario logo. He says he hasn’t played video games much since becoming Uber’s chief executive but is a fan of racing games such as Mario Kart, as well as Nintendo’s Wii Tennis and Angry Birds. “At the peak, I was number seven in the country on Angry Birds.”

He’s proud of this? “Of course!” he says, smiling but entirely serious. “If somebody gives me a casual game and says, ‘OK, here’s the world record,’ I’ll just go until I’m there.” When I confess to an addiction to Clash of Clans, an iPad strategy game with a cartoony Game of Thrones-like theme, Kalanick admits to his own “guilty pleasure”: Candy Crush Saga , which has topped the App Store charts over the past year. He has reached level 173 – pretty decent, I say, but unlikely to be in the country’s top 10. “You don’t start at the top in the world”, he says, “so don’t rile me up.”

He has finished his sandwich and is picking at a cup of thin-cut French fries, wrapped in faux-newsprint (in Silicon Valley, old-fashioned newspaper isn’t even useful as fishwrap). As his greying hair hints, Kalanick hasn’t always been on top. Brought up in a Los Angeles suburb, he dropped out of UCLA in 1998 to join Scour, a start-up founded by fellow computing students. This proto-Napster file-sharing service ended badly, with legal actions from media companies. In 2001 he took many of Scour’s engineers to form Red Swoosh, a more legitimate peer-to-peer application. In 2007 it was sold for about $15m. By Silicon Valley standards, that’s almost a failure, but it left Kalanick with enough money to invest in other start-ups, including Uber. “In my last company, where I wasn’t making a salary for the first four years, you learn the lesson hard of being too early. Holy cow, you feel it. So then you get really good at timing.”

Uber’s rapid revenue growth (20 per cent a month) is pegged in part to that of the smartphone market. But it also fits the wider trend of internet companies grappling with the physical – “software eating the world”, as venture capitalist Marc Andreessen puts it. After Google’s experiments with self-driving cars, its investment in Uber last year triggered visions of robo-taxis. Kalanick says he has ridden in one of Google’s cars. “It’s a beautiful thing, oh my gosh.” But the technology has “a way to go”.

He reels off a series of manoeuvres that are simple to human drivers but would flummox a robo-car: entering a freeway, driving around a double-parked delivery truck, even dealing with rain. Does Uber want to solve all these problems itself or is he happy outsourcing it to Google? “Anything that’s important to the company, we won’t be outsourcing,” he says.

So Uber has its own team working on robo-vehicles? “I didn’t say that; don’t mess with me. I didn’t say that.”

He didn’t say he doesn’t, either, but he bounds on. “It will definitely happen in our lifetime. The question is when and ‘Can that happen faster?’”

We part, though he doesn’t check whether our bill blew the FT’s budget, as he’d been keen to do 90 minutes earlier. But it certainly wouldn’t count as “surge pricing”.

Tim Bradshaw is the FT’s San Francisco correspondent

——————————————-

Bluestem Brasserie

1 Yerba Buena Lane,

San Francisco, CA 94103

Iced tea $2.50

Iced tea and lemonade $3.00

Half-dozen oysters $15.00

Steak sandwich $17.00

Acorn-fed pork belly $17.00

Total (incl tax, service) $61.05

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Meal is deserved after long march / From Mr Richard Wilding

Comments