Social media finfluencers embrace the rules to reach a new audience

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is the latest part of the FT’s Financial Literacy and Inclusion Campaign

TikTok and Instagram are the last places most older savers would hunt for financial advice, but for young people social media platforms are spaces they’re increasingly consulting for information.

“The genie is already out of the bottle: you’re not going to be able to stop people from posting online,” says Timi Merriman-Johnson, a 33-year-old content creator, widely known as Mr MoneyJar. “That’s where younger people are going to get financial advice.”

Awaiting them is an ocean of cryptocurrency, high-frequency trading and “meme” stocks as influencers promote risky investments, pledging eye-watering returns. It’s a murky world where regulators are working hard to prevent unscrupulous operators taking money unfairly — and often illegally — from young people.

But navigating these choppy waters is a growing group of young financial professionals with a different approach from the rule-breaking scammers — they want to provide straightforward guidance on subjects such as pensions, tax and balanced portfolios.

Beware impersonation scams

Online impersonation is a big issue, raised by several popular IFAs interviewed by the FT. They highlighted the proliferation of fake accounts which dupe followers into sending money for investment purposes.

Emmanuel Asuquo, a 37-year-old IFA and content creator, says he has been contacted by individuals who have fallen for scams involving someone impersonating him, costing them thousand of pounds.

James Shackell considers Instagram simply “too scammy”, with fake accounts a particular problem, but he adds that YouTube also has problems with bots.

TSB reported in May that some 80 per cent of all purchase, investment and impersonation fraud affecting its customers involved scams through Meta-owned Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram.

It has attempted to leverage findings to protest against the government’s decision to scrap plans forcing technology companies to compensate victims of online financial scams.

Asuquo says he still prefers to use Instagram over other platforms due to its reach and the potential for partnerships. “Instagram was the main platform when I started five years ago as it’s really good for brands.”

Merriman-Johnson is among them, having built a following of 17,000 on Instagram with simple posts on savings and pensions. Now training to become an independent financial adviser (IFA), he and several others hope to use their professional experience to transform the quality of financial guidance available online and make money through partnerships with banks, charities and other businesses.

Alongside regulators, they believe they can make a difference. The Financial Conduct Authority in July announced new guidelines for financial influencers, including proposals that require companies to monitor the output of influencers they pay to promote products.

“We see the space that is inhabited by influencers as a key one for us to engage with,” says Lucy Castledine, director of consumer investments at the Financial Conduct Authority. While a lot of the regulators’ attention is concentrated on the suspected rule-breakers, she says influencers play a prominent role in how the FCA engages with younger audiences.

The Financial Times spoke with eight influencers, including four who recently pursued an IFA qualification, the primary route to providing legally compliant financial advice in Britain.

New types of content

“Some people like to be controversial,” says Kia Commodore, a 25-year-old content creator who runs the financial guidance page Pennies to Pounds.

She started out on X, formerly known as Twitter, and YouTube before focusing on Instagram where her posts centre around buying a first home and saving for retirement. Such themes, she says, were overlooked in the community where she grew up in a deprived district of London. She says her ambition now is to produce “jargon-free” content rooted in “accuracy and value”.

Several months away from qualifying as an IFA, Commodore says formal training was an important part of legitimising her personal brand Pennies to Pounds. She earns an income through paid partnerships and speaking engagements.

Commenting on the misleading financial promotion online, she says content has become fast-paced and difficult to check. “On TikTok, if you consume anything on personal finance you’re not seeing anything about the creator,” she says. “If you’re consuming bursts you don’t have time to understand a person’s background.”

Some online content fails to carry adequate explanations of risk, according to James Shackell, 33, a partner at Nova Wealth (previously Octopus Wealth) based in London. “When people learn about crypto, they hear that they might get a 30 per cent yield,” he says, arguing that this leaves people thinking there are “free lunches”.

Shackell’s day job as a financial planner is combined with his YouTube channel, which generates ad income and has around 84,000 subscribers, and includes videos of him explaining index funds and retirement strategies.

While both have different audiences — Commodore skews towards those at the start of their savings journey, and Shackell leans more towards an older demographic aged 55 and over — they both aim to provide sober guidance.

Content creators are also diversifying. London-based Bola Sol, 31, says she has grown more confident discussing property for example, and has started creating podcasts. The financial coach and personal finance columnist says she has also started publishing a series geared towards working-class young people seeking a window into the lives of high-earning professionals.

A current Instagram series involves asking individuals earning six-figures sums about their budgeting and saving habits as well as any financial regrets they might have.

But Sol cautions other would-be influencers not to underestimate the demands of posting financial content online, particularly as rules mean posts should avoid offering person-specific advice.

The FCA allows general “guidance” but not targeted “advice”. Sol says: “This type of content creation is nuanced. I studied maths and finance, I have an awareness of the rules.”

John Somerville, head of learning at the London Institute of Banking and Finance, a provider of IFA certification, says: “If creators aren’t educated enough, there’s a risk that somebody may be put into some form of financial distress.”

Dealing with rogue influencers

For regulators, the guidance-orientated influencers are potential allies in the fight against scammers.

The FCA has partnered with 15 influencers to date, including Merriman-Johnson, and is in the middle of a five-year £11mn “InvestSmart” marketing campaign. Aiming to dissuade risky investment behaviour, the regulator has published blogs and paid influencers to help reach younger audiences.

These moves go hand in hand with increased efforts to clamp down on rogue companies and their paid promoters.

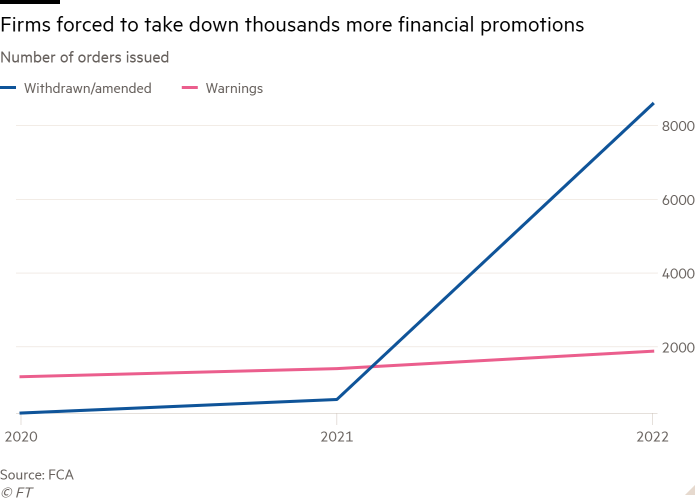

The regulator took action against an unnamed finfluencer last year after they promoted “unauthorised traders” to followers. It was one of more than 8,500 cases in which the FCA intervened to force firms to amend or withdraw a online promotion last year, up from 572 in 2021.

Castledine says the regulator is on track for a similar total this year. The FCA took down 2,235 promotions in the first quarter of the year. But regulators are still wary of partnering with financial influencers, even IFAs, as these creators can stray across advice/guidance boundaries.

“I do watch some content, and think, ‘oh, you’re not worried about the FCA at all are you?’” says Sol. She adds that the accessibility of social media means new creators crop up frequently and produce content that takes advantage of people. “Day trading, cryptocurrency and pyramid schemes, those three I’m never interested in.”

Somerville says that IFAs must stay on top of legal requirements, including online, knowing they risk financial penalties and possible loss of licence for rule breaking.

Merriman-Johnson says IFA training means he can now cover “the full spectrum” of topics, including taxes and pensions, as well as debt, savings and investment.

“The training helped me in terms of tax, pensions and savings,” says Francesca Henry, a recently qualified IFA, known online as MoneyFox. Having started out by detailing her journey cutting her own credit card debt, she now produces content ranging from budgeting to insurance.

Though qualified IFAs are trained to understand regulatory frameworks, there is still a risk that they breach financial promotion rules, particularly by handing out advice. “That’s where it will fall foul of our financial promotion rules and where warnings and take down requests come in,” Castledine says.

Mind the gap

However, the need for advice is growing. FCA figures show that only 8 per cent of the population — most of them over 45 — pay for financial advice. This leaves a widening advice gap for millions, especially younger people. The FCA is reviewing the advice/guidance boundary, including proposals to streamline advice.

Sol says there’s no reason why accurate online content cannot aid young people, particularly as it’s free and accessible. “I’m not telling people where to invest, but they don’t even know how to get started,” she explains, adding that she often guides people to an IFA.

But regulated IFAs are generally older people who do not always appeal to young savers. Fewer than 6 per cent are under 30, says the FCA.

Mike Barrett, a director at consultants The Lang Cat, says: “The sector is evolving very slowly, it is a little bit more representative in terms of age and gender, but it is still dominated by older, more established financial planners.”

So for many young people, social media will remain the favoured first step for financial guidance — despite the risks that it sometimes involves.

Which platforms and services make for the best content?

Social media is a broad church offering a variety of platforms with pros and cons for any independent financial adviser influencer.

James Shackell says YouTube and its ability to accommodate long-form video enables him to explain topics in detail and explore a range of scenarios, making his content more specific than on other platforms. “With 30-second videos, you’re never going to be able to give people the depth of information they need.”

Platforms offering shorter content tend to have younger audiences, with LinkedIn having a higher average user age than, for example, Instagram.

Several influencers said Instagram offered a helpful landing page, enabling them to post evergreen content. Sol says she receives requests to post sponsored content on TikTok more than other platforms. She says creators should ensure any product they market aligns with their own values.

“I live on Instagram, that’s where I dedicate most of my time,” says Henry. “People are more likely to reach out to you. They can connect to you more as a person. With TikTok, you see them as and when.”

Most influencers juggle content creation with a full-time job, meaning working late evenings and weekends filming, editing and posting.

Merriman-Johnson opts for Instagram, but also has a presence on TikTok and LinkedIn. The latter has become a useful landing page for IFAs in general, enabling them to reach working professionals, a traditional customer base.

He adds: “You can post on LinkedIn if you want to share a stream of consciousness and for quick bits of text there’s Twitter [now known as X]. TikTok has the viral aspect and YouTube is a great platform depending on how long the content lives on there.”

Comments