Gillian Tett: Look back to judge chances of a global future

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

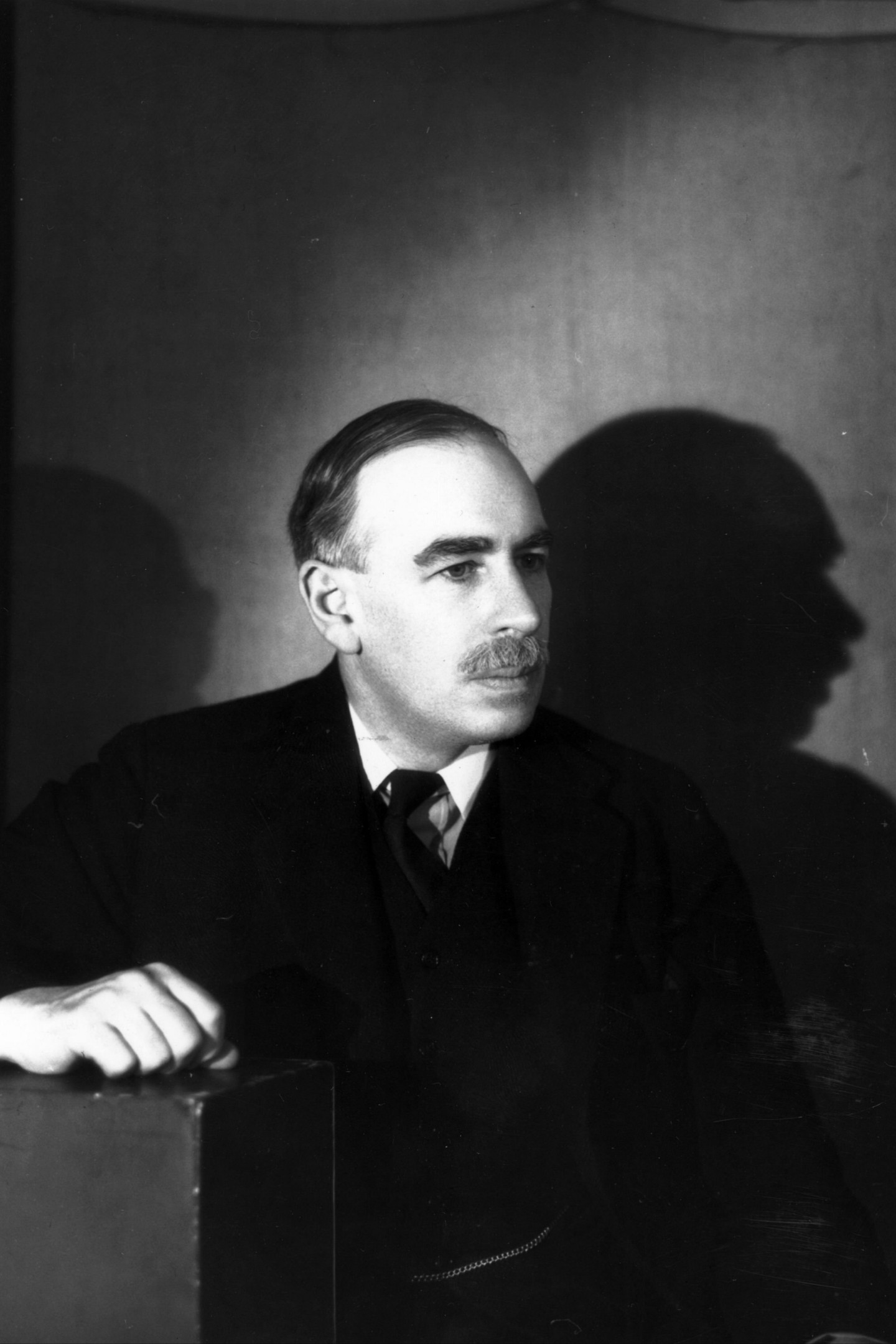

Just over a century ago, John Maynard Keynes lamented the dangers of being complacent about globalisation. In 1919, in his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Keynes noted that, before the recently ended first world war, “the inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep.”

He (economists assumed, then, that economic actors were male) could “adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world” and “secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality”. Moreover, this state of affairs was “normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement”.

Thus “the projects and politics of militarism and imperialism, of racial and cultural rivalries, of monopolies, restrictions, and exclusion were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper.” In plain English: people had taken globalisation so completely for granted that they rarely gave it much thought — and assumed that the free movement of people, money and objects would continue indefinitely. War had seemed like a relic of the past.

Fast forward a century, and it is tempting to laugh or cry at this state of affairs. After all, during the 1914-18 conflict, such sunny complacency had been shattered by massive economic destruction, the closure of borders, disruptions in trade and a fractured capital market.

Globalisation had gone into reverse. Further, the war was followed by the 1929 economic crash, depression and protectionism in the 1930s and, then, another world war. Although globalisation resumed in the middle of the 20th century, it was not until the century’s end that the world returned to the type of globalisation that Keynes observed — ie, a world where it seemed so normal to move goods, capital and ideas around that most observers assumed this would continue indefinitely, and deepen. The only big difference between 2013 and 1913 was that, in the modern era, no one expects to travel “without passport or other formality” across borders. Today, there are inevitably bureaucratic controls.

The chilling question we face is whether we are about to see a replay of Keynes’s tale — namely, an era when globalisation suddenly goes into reverse, as geopolitical conflict rears its head again. So far, the answer is “not entirely”. For, while the political rhetoric in many countries has become lamentably populist, protectionist and nationalist, globalisation is far from dead.

To appreciate this, look at an annual survey from the DHL shipping group and NYU Stern School of Business. This explores globalisation in terms of four measures: the movement of people; information; money; and trade. The latest reading, conducted in May 2023, shows that the flow of people is lower than a few years ago, primarily because travel has yet to recover from Covid-19.

But exchanges of information continued to rise in 2022 (albeit at a slower pace than before), while cross-border money flows remained moderately strong and those of goods and services actually rose — leaving world trade 10 per cent higher in 2022 than in pre-pandemic 2019. As a result, the overall globalisation metric, as calculated by DHL and NYU Stern, is still rising slightly.

Although US-China trade has declined, there is “no broad fracturing of the world economy into rival blocs” and “most [trade] flows contradict predictions of a shift from globalisation to regionalisation” — not least since supply chains have become more complex.

The report admits this picture might be temporary because “the public policy climate has become less favourable for globalisation.” Steven Altman, a senior research scholar at NYU Stern, warns against inferring “from the recent resilience of international flows that globalisation cannot go into reverse”.

And when, in October in Marrakech, the IMF held its annual general meeting, its World Economic Outlook included a depressing new feature: a section calculating what might happen if the world slides into a new “Cold War” of two rival geopolitical economic blocs that do not trade with each other.

To (gu)estimate that, the IMF used a model based on the political grouping that emerged at the UN during 2022’s Ukraine vote: namely pro-western and anti-western blocs. It calculated that, if a true cold war emerges, it would cut future global GDP by up to 7 per cent due to lower trade, finance and information flows. Other economists put the figure even higher.

The IMF stresses that such a scenario is theoretical and hopes — by showing policymakers, and voters, the folly of letting globalisation wither — to ensure it never occurs. Yet, the fact it published this “abstract” exercise shows how the world has changed: a decade ago, in 2013, the idea globalisation might go into reverse was as alien as it was in 1913.

Perhaps, then, it is time to republish The Economic Consequences of the Peace — or transmit its message out on the globalised internet.

Comments