The empire of Alain de Botton

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

On a recent Thursday morning, I flew to Amsterdam to meet the writer and philosopher Alain de Botton. As I woke up and left the house, I couldn’t help noticing how much of the minute-by-minute experience of being alive that day had been described and analysed by the signature highbrow self-help books that de Botton has been writing for the past 20 years.

I was making a journey (The Art of Travel, 2002); I was flying from Heathrow (A Week at the Airport, 2009). On the way, I looked at billboards of barely-dressed men and women (How to Think More About Sex, 2012) and checked my phone for news (The News: A User’s Manual, 2014). I was on an early-morning flight, full of people in suits looking at spreadsheets on their laptops and worried, as usual, about my choice of profession (Status Anxiety, 2004). As the plane took off and we rose into a fragile orange dawn, I thought first about death (Religion for Atheists, 2012) and then about how much I was looking forward to seeing the streets and canals of Amsterdam, a city I had never previously visited (The Architecture of Happiness, 2006).

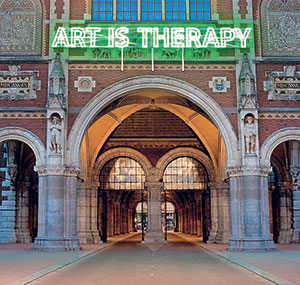

Sometimes it can feel like it’s a de Botton world and we’re just living in it. Working at what he describes as “the interaction between culture and life”, he has sold 6m books. He was in Amsterdam to give a talk for the opening of his Art is Therapy show at the Rijksmuseum. Concurrent shows are under way at Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne.

Art is Therapy is quintessential de Botton. The man wants our attention in a busy, distracted world. As a result his books, with their catchy, polemical titles, have often taken on tangible forms: at his School of Life, which will soon have branches in Australia, Turkey, France and Brazil; in his Living Architecture range of modernist holiday homes; in his Philosopher’s Mail website, which describes itself as “a genuinely popular and populist news outlet which at the same time is alive to traditional philosophical virtues”. The empire has earned him a reported £7m.

Art is Therapy has the same origins. Last year de Botton published the book Art as Therapy, with the art historian John Armstrong. It argued that our relationship with the visual arts, particularly in the context of big art museums, has lost its way and we need to find new ways to reconnect with paintings and sculpture on a personal and emotional level.

Before the lecture began, I had time to look at de Botton and Armstrong’s Rijksmuseum intervention, which consists of about 150 large, yellow, Post-it style labels that have been stuck around the place, encouraging people to interpret their visit in broadly therapeutic terms. The captions were instantly recognisable as de Botton’s: witty, academically self-aware, eager to embrace our vulnerabilities. “There is no such thing as great art, per se,” said a sign on the stairs, “only art that works for you.”

At first glance, the art museum struck me as a curious target for de Botton’s concern. The Rijksmuseum, which reopened last year after a major (and universally lauded) refurbishment, was packed. It seemed to be doing fine. Three million people came to see its collection last year and, around me, they were doing what people normally do in big museums. They steeled themselves before floorplans. They ate apples on benches. They followed guides who waved pieces of paper above their heads.

But this is exactly the kind of aimless experience that de Botton is worried about. He wants us to engage with visual art with the shock and immediacy of feeling we associate more naturally with music. One of his yellow signs was next to “The Feast of St Nicholas”, a painting by Jan Havicksz Steen from the 1660s. At the centre of the image an impish little girl with a bucket of treats backs away from a friendly-looking woman. De Botton’s label suggested that the work takes a tolerant view of the greedy child within us all, and might help us with our feelings of “fragility, guilt, a split personality, self-disgust”. A tall man standing looking at it, who turned out to be an insurance manager from Florida, had his own interpretation. “It reminds me of occasions when you get your family together, and you think it’s going to be fun and tranquil,” he said. “Then it turns into chaos.” He squinted sceptically at de Botton’s text. “He didn’t talk to the painter, did he?”

Other people loved the signs. Because I was wearing a press badge, I was mistaken several times for a tour guide and one woman – also American, from Salt Lake City – came up to me specifically to ask who had done them. “These are brilliant, honestly,” she said. She was called Kathy. “I think it makes people stop and put it in a perspective that they are not capable of.” She wrote down de Botton’s name in her notebook.

In the lecture hall de Botton laid out the main argument of Art as Therapy with the help of slides and jokes. In person, he is a mercurial presence: trim, fine-featured, fluttering with an energy that reads as politeness rather than nerves. He has clear skin, a large soulful mouth, sea-green eyes and an astonishingly smooth bald head (he lost his hair when he was 20). He spoke for 35 minutes without notes, dashing around the history of art and our struggle with its purpose in our lives in a tone that was companionable, clever, admitting of our faults.

“We are all very anxious,” said de Botton, in a riff about the calming effects of minimalism. “You’re anxious. I’m anxious. We’re all very anxious.” All the big names – Aristotle, Ruskin, Hegel – got a look in but colloquially so. Vermeer, Rembrandt, de Hooch – the masters who fill the Rijksmuseum – were always “the guys” or “the 17th-century guys.” When he finished, he took the banal questions of journalists and threw them back in brilliant forms. He was like a bashful boy genius at a prize-giving.

So why do you infuriate so many people? I asked. We were back in the lecture theatre, alone. De Botton had just led a quick tour of the Rijksmuseum’s “Gallery of Honour”, followed by television cameras. Like many of his most ambitious projects, Art is Therapy has received some poisonous reviews. “De Botton’s evangelising and his huckster’s sincerity make him the least congenial gallery guide imaginable,” wrote the Guardian’s art critic Adrian Searle. Such hostility has stalked de Botton since his breakout hit How Proust Can Change Your Life was published in 1997. “This reviewer was, unfortunately, intensely irritated by many aspects of de Botton’s thesis, finding it superficial, often contrived and at times patronising,” wrote Teresa Waugh in the Spectator. That morning, a Dutch journalist had turned to me and said: “I suppose he sees himself as a modern Socrates, going around and annoying everybody.”

Early negative reviews of his work, by Proust professors and philosophy dons, devastated him, admitted de Botton. “It was very surprising and upsetting. Then my wife, who is very wise, said to me, ‘It’s obvious, this is a fight.’ This is a turf war, and the battle is about what culture should mean to us.”

De Botton studied history at Cambridge. He started a PhD but chucked it in, turning against the academic establishment. Now, whenever he roves into a new field – asking what Proust, architecture, philosophy, or art museums can do for us – he girds himself for the same embattled responses. “You’ve got academic philosophers going, ‘This guy has sold 22,000 times as many books as any philosophical books we’ve written, therefore he is killing us,’” said de Botton. “He is not allowed to exist.”

De Botton is certainly the victim of professional envy. He comes up with snappy ideas. He is unbelievably productive (he rarely sleeps past 6am). He gives YouTube lectures. But all this still doesn’t quite explain how intensely he gets under people’s skin.

I decided to read out loud a bit of de Botton that I found particularly irritating so we could talk about why. “We need celebs to make a whole lot else sexy,” he wrote recently about famous people and their endorsements, “including reading, being kind, forgiving and working towards social justice.” Yuck, I said. Ghastly.

It was a mistake. De Botton looked at me. He might be supremely comfortable talking about Le Corbusier and the nature of loneliness but this was clearly pushing it. He gave me a rather dizzying lecture about the stupidity of giving interviews – “You put yourself in the hands of somebody who is deeply unsympathetic to what one is trying to do and it gives them the leeway to say any old thing” – and the crudeness of asking him why he thinks he drives other people crazy. “It’s a question one can have about a person,” said de Botton, “but it’s not necessarily a question that that person can answer.”

Fair enough. Despite his relentlessness, the guy has nothing to prove. For every critic in the Guardian, there was John Updike, who found de Botton dazzling. For every insurance manager from Florida, there is a Kathy from Salt Lake City. The books, the sales, the franchised Schools of Life speak for themselves. Whatever emotions he provokes, de Botton is completely plugged into the psychological terms of our age.

A few weeks before we met, I had attended a class on “How to Realise Your Potential” at his School of Life near King’s Cross in London. On a weekday afternoon, costing £40 a head, it was practically sold out. I sat with about 25 others – students, overworked professionals, people recovering from serious illness – as we were guided for two hours through the aperçus of Rilke, Emerson and the sociologist Richard Sennett on how to live a fulfilled life and balance the competing demands of your work, yourself and other people. The tone was secular, humane and smart. My brain buzzed with cynicism about being there and the scale of my imperfections. The rest of the class just got on with it, talking about the passion that had gone out of their jobs, the friends who bored them, their eagerness to retake control of the narrative of their lives. “Everything is fluid,” said a woman who had lost her mother and discovered she had leukaemia a few months later. “Nothing is as bleak as it seems at the time.”

…

Back in the lecture theatre, the mood between us improved. De Botton more or less interviewed himself. “It is self-therapy before it is anything else,” he said. He was born in Switzerland in 1969, a weedy boy, and came to England when he was eight. Unable to speak the language, he was packed off to boarding school. Art – literature, paintings, music, buildings – became the young de Botton’s solace, his companions, a way “to see into the minds of others and feel you are not alone”. The captions in the Rijksmuseum can at times read as a direct, autobiographical plea for the work to mean as much to you as it has done for him. “I want my mummy,” says the label next to a 14th-century Buddhist statue, “even if I’m 44 and a half.”

His forebears made money. His father, Gilbert, sold the firm he founded, Global Asset Management, in 1999 for $675m. “Sometimes my biography is interpreted as the upbringing of a French aristocrat,” de Botton said to me. “It was very, very different. We were a family of mercantile, immigrant Jews.” Everyone was ambitious. Everyone was paranoid. “I was told by my father nine times a day that you were going to get a job the minute you finish your studies.” Hence the momentousness, in de Botton’s eyes, of the decision, aged 21, to write for a living. The guilt. The shame. The need to be prosperous (he has never touched his inheritance). “My father really respected culture but only the successful people,” he said. “He had no patience for the starving artist.”

The mystery, which de Botton has since solved, has been the ache to connect. To grasp the middlebrow. Why does he care if millions of people are trudging around palaces of high culture and not having a particularly good time? The answer is his nanny. De Botton was, in large part, brought up by a woman called Bertha Von Buren. He spent much of his childhood in her village of Ennetmoos, in rural Switzerland. “She looked after me until I was 13 and she is still who I look to as my mother,” he told me. “She was the wisest person, and the kindest person, that I ever knew …and she’d never read a book in her life.” He still spends every summer in Ennetmoos, now with his own family. His father is dead; Bertha is still alive. “A very intelligent chap told me once that you are trying to write books that both your father and your nanny will understand,” said de Botton. “That is your existential situation.” He recounted all this without a single pause. “I thought that was the most brilliant comment. It explained everything.”

We went outside, into the sunshine. He likes being abroad. “I think it is very possible that my deeper character is not very English,” said de Botton. “I do weird, European, confessional heart-laid-bare stuff. I have a kind of utopian streak …England is an empirical country of cynics, you know. It’s Will Self.” Around us, Amsterdam, where de Botton had opened a School of Life the afternoon before, looked much more promising. “I’m very idealistic about this country,” he said. “But what’s it like to live here?”

We sat in the Rijksmuseum’s garden. De Botton talked about some of the writers he loves – Montaigne, and the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott – and then he told me about a service, known as “bibliotherapy”, offered by the School of Life, which (I think) he thought I would hate. The idea is that someone suggests enriching books for you to read. “What a load of wank!” he exclaimed, gleefully taking the role of his detractors. “What do I want to say? Just calm down …” It occurred to me, as it has long occurred to him, that our reactions to him might say more about ourselves than they do about him. “Is this the enemy?” He asked. “Is this really the enemy?”

At the airport, in de Botton-ish fashion, a songbird was trapped inside the terminal and fluttered about the rafters. I checked Twitter. De Botton is, of course, on the site. He has 439,000 followers. His profile picture is of a seascape by the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto that he claims is useful for countering anxiety. He had just posted a message.

“The best cure for one’s bad tendencies,” he wrote, “is to see them fully developed in someone else.”

‘Art is Therapy’ at the Rijksmuseum runs until September 7

Comments