Fuelling Isis Inc

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Waiting for his job interview, the young Syrian was impressed by the array of high-end camera equipment, video-editing pods and overall organisation in the offices of his prospective employer. The salary, five times that of a typical Syrian civil servant, was not bad either.

“They offered me $1,500 a month, plus a car, a house and all the cameras I needed,” says the one-time tailor in his late 20s. “I remembered looking around the office. It was amazing the equipment they had in there. I remember thinking, these people can’t just be getting their money on their own. There has to be a state behind this.”

His prospective employer, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, the al-Qaeda offshoot known as Isis, has pretensions to being a state but it is not there yet. The group controls a third of Iraq and a quarter of Syria but the young man was not being recruited to take up arms. Instead, he was being hired to work at the group’s media office – the sort of operation more often associated with multinationals – in Raqqa, the Syrian city that is the de facto capital of the group’s self-declared Islamic Caliphate or state.

He chose not to take the job – staying in Syria was too dangerous, he decided – but the story illustrates the level of resources and funding available to the terror group that has grown out of the Syrian conflict into an organisation that President Barack Obama committed the US to “degrade and ultimately destroy” this month.

Strangling the source of that revenue – which estimates put at anywhere between $1m and $5m a day – is seen by the US and its allies as essential to halting the Isis advance.

10The number of oil fields under Isis control in Syria and Iraq

Western investigators have sought to trace bank account numbers in the Gulf and locate jihadi donors as far afield as Indonesia. In addition to nefarious ransom and extortion rings, Isis taps areas under its control for money, charging retail stores about $2 a month in taxes. In coming days, it plans to charge for electricity and water consumption to make money in areas under its control, according to one activist in Syria.

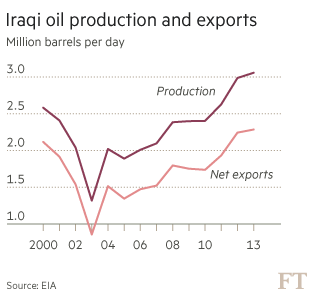

But experts say that to crack down on Isis’s finances, western governments and their Middle East allies must look first at a decades-old oil smuggling network, which is now being tapped by the group to finance its proto-state. This lucrative unofficial trade encompasses northern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southern Turkey, parts of Iran and, according to western officials and leading international experts, is where Isis earns the bulk of its money.

Maplecroft, the risk management firm, says in a recent report that Isis now controls six out of 10 of Syria’s oilfields, including the big Omar facility, and at least four small fields in Iraq, including those at Ajeel and Hamreen.

Oil smuggling has deep roots in the region. After the imposition of UN energy sanctions on Iraq in the 1990s, a robust network of smugglers, traders and bootleg refineries have flourished.

171Iraq’s ranking in Transparency International’s corruption index

Hundreds of entrepreneurs emerged, buying and selling small parcels of Iraq’s oil at discounted prices and transporting them across the Turkish border to sell at a markdown. Many of the business people have grown rich and powerful, with vested interests and political ties.

Energy experts and western officials say Isis may be laundering up to 80,000 barrels of oil a day worth several million dollars through this shadow market. The oil is smuggled through rugged mountain and desert routes or even legitimate crossings at Reyhanli, Zakho or Penjwan for consumption in Turkey, Iran or Jordan.

“The fact that Iraq was under sanctions for so long led Kurdish and Iraqi businessmen to fill a vacuum and create smuggling networks for Iraqi oil,” says Valerie Marcel, a Middle East and Africa energy specialist at Chatham House, the London think-tank. “Turkish, Iranian, Syrian, Iraqi networks have grown because of decades of bans on exports. From Iraq and now from Syria there is this grey market. That’s becoming a huge problem.”

Black market oil is often refined at plants in Iraqi Kurdistan that are partly the byproduct of the tensions between Kurdish leaders and Baghdad. In recent years the Kurdistan Regional Government looked the other way as homegrown refineries popped up to supply the local market after Baghdad banned the export of petroleum products without its consent.

This means that the Kurds are potentially helping put money in the coffers of the jihadi group that its own peshmerga forces are fighting. “It’s now possible that Isis could be selling crude [via middlemen] to these knock-off refineries,” says Bilal Wahab, an energy expert at the American University of Sulaymaniyah. “The KRG is unwilling to shut them down because it would have to raise the price of gasoline. It can’t raise the price of gasoline because it can’t pay salaries, and it can’t pay salaries because the central government hasn’t given the KRG its budget in eight months. Yes, it’s illegal. Yes, it’s bad. But it is what greases the wheels of the economy.”

International officials accept that the bulk of Isis’s funds are raised within the vast areas of Iraq and Syria it controls.

“It’s pumping oil and selling it to fund its brutal tactics, along with kidnappings, theft, extortion and external support,” John Kerry, US secretary of state said last week. Asked if the administration was looking at bombing oilfields or refineries controlled by Isis, Mr Kerry said: “I have not heard any objection.”

The boundaries of the mostly Kurdish black market zone have never been easy to police, rarely recognised by people with cross-border kinship and trade ties. The terrain ranges from the grassy plains dividing Turkey from northwest Syria to the forbidding mountains between Iraqi Kurdistan and its Turkish and Iranian neighbours to the flatlands along Iraq and Syria’s Jordanian borders.

Smuggling underpins the economy of the semi-autonomous, three-province KRG with smugglers’ coves dotting its borders with Iran, Syria and Turkey. In towns like Hajj Omran along the Iran-Iraq border smugglers openly regale visitors with tales of their exploits.

Iraqi Kurdistan officials warn they have limited resources to police the trade – it now shares a 1,000km border with Isis – and complain that funds have shrunk since Baghdad began withholding budget revenues to the region, another example of how Iraq’s political divisions benefit Isis.

“The government is doing all it can to control the borders,” says Sherko Jawdat Mustafa, a member of the Kurdistan region’s parliament. “But recession is prevailing over Kurdistan with all its institutions and apparatus.”

Officials also suspect border guards in Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey are bribed to allow shipments to pass. “It’s like a drug cartel and a criminal organisation which is also benefiting from official support or [those in power] turning a blind eye,” says Ms Marcel. “It couldn’t exist on the scale that it is right now without some army and customs people being complicit and benefiting.”

Oil fundThe Islamist group now controls 10 oilfields including the big Omar facility in Syria and those at Ajeel and Hamreen in Iraq

Iraq ranks 171 out of 177 in Transparency International’s 2013 ratings of perceived official corruption. Security forces often look the other way in exchange for a cash payment.

“A lot of money also goes to the guys at the checkpoints,” says Mr Wahab. “So you have to enforce accountability at the checkpoints and find ways to keep them from taking bribes.”

A Turkish official recently said seizures of smuggled fuel had risen from 35,260 tons in 2011 to more than 50,000 tons in the first six months of 2014 alone, suggesting an explosion in the trade. But the market appears to have shifted in recent weeks in response to a tightening of Turkish border controls.

Self sufficientIsis charges stores $2 per month in taxes and is set to introduce electricity and water charges

Much of the trade is carried out inside Isis-controlled areas, making efforts to curb it even tougher. “Now most of the traders are Iraqi,” says Othman al-Sultan, an activist in the Syrian city of Deir Ezzor. “All the Iraqi traders come to buy the crude and take it back into Iraq. Syrian crude is cheap and they use it for generators and factories in Iraq.”

Isis has sought to divorce itself from dependence on international donors in its efforts to create a self-sufficient economy since establishing itself as a significant presence in the Syria conflict. It was in part a disagreement over whether to raise funds locally or internationally that led to friction with other Syrian rebel groups, including the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al Nusra.

Analysts suggest tracking down account numbers or arresting international supporters will do little to damage the finances of a group that deals almost exclusively in cash. Most Gulf supporters seeking the removal of Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian president, are now largely shunning the group.

“Given that the Islamic State has sought to minimise its reliance on the international banking system, the group is comparatively less prone to asset seizures or international financial sanctions,” says the Maplecroft report.

Big earnerAnalysts believe oil represents the single biggest income stream for Isis with the bulk of raised inside its area of control

In addition, the group is believed to have distributed its money across a wide geographic area. “Stopping smuggling operations will not affect the Islamic State in the short run,” says Hisham Hashemi, an authority on Sunni insurgents in Baghdad. “They have enough money – in cash – that could keep them going for a good two years.”

But Isis’s outsized ambition and refusal to compromise might lead to the downfall of its financial empire. Isis’s pretensions toward statehood have compelled it to attempt to take control of the entire process and cut out the middlemen. There are also signs that international momentum is building to stifle the black market oil trade. The governments of Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan have announced fresh interdiction efforts. Prices of crude oil in Syria have risen from $25 to $41, suggesting decreased production following Turkey’s clampdown on the border, an activist says.

At the smuggling village of Hacipasa, near the Syrian border, residents recently railed at government efforts to block illegal border crossings that provide a livelihood for many Turks. If the recently installed Baghdad government of prime minister Haider al-Abadi resumes long-delayed budget payments to Kurdistan, it would create even more of an incentive for Kurds to crack down on bootleg refineries that purchase black-market oil.

“Isis is trying to take the oil products as close to the end user as possible to capture more profit,” says Ms Marcel. “By doing that, Isis’s finances become probably easier to target than a constellation of little middlemen with small volumes crawling around the whole territory.”

Additional reporting by Piotr Zalewski in Ankara, Geoff Dyer in Washington and Lobna Monieb in Cairo

Comments