When Walt went to China

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is hard to think of two organisations that love synchronised dancing more than the Disney corporation and the Communist party of China. So when the two came together for the opening ceremony of Disney’s new $5.5bn theme park in Shanghai, the display was unsurprisingly choreographed to perfection.

Buzz Lightyear, Princess Elsa, Winnie the Pooh, Captain Jack Sparrow, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck: the full weight of Disney’s intellectual property holdings was arrayed in phalanx in front of the world’s largest Disney Palace — and China’s watching politburo — each dancing toy action figure, princess or superhero representing a discounted cash flow in the billions of dollars.

Fireworks, speeches, more fireworks, more speeches: there was not a lot of room for subtlety. This was, after all, the world’s biggest entertainment company celebrating its beachhead into the world’s fastest growing entertainment market. Everything was done to reinforce the impression that we were watching a salient event in the recent history of the world, the formation of a new strategic partnership or new power sharing agreement — that the global entertainment industry was now a US-China duopoly.

Yet Disney’s journey to Shanghai has been long and fraught, underlining Beijing’s schizophrenic relationship with mass American culture. Western brands are a particular neurosis for China — Mark Zuckerberg, for example, is treated as a celebrity whenever he comes to China, but Facebook remains blocked. Luxury brands such as Gucci count China and Chinese tourists as their main market, but also their most prolific copier and counterfeiter. That China has not yet created a globally successful brand is a peculiar source of humiliation in Beijing amid soul searching as to why.

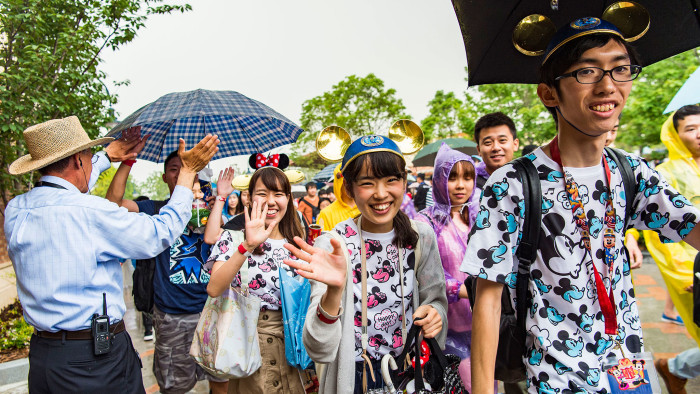

The Disney launch date had been set for the numerologically fortuitous 6/16/2016. Six is a revered number in China, a homonym for the word “liu”, meaning “smooth”. But bidding for the smoothest karma possible also placed the opening ceremony during Shanghai’s rainiest month.

Not that the party hierarchs were put off by the light drizzle. Wang Yang, vice-premiere of China, insisted that it was in fact a “blessing” — representing “a rain of fortune, a rain of US dollars and renminbi”. Bob Iger, Disney’s chief executive, murdered some Chinese: “We make dreams come true,” he said twice before getting the intonation right. Letters from Barack Obama and Xi Jinping were read out to give the ceremony a heft of statesmanship: Obama insisting the resort “captures the promise of our bilateral relationship”; Xi that it demonstrates China’s “commitment to close cultural co-operation and our innovation mentality in the new era”.

There was a time when China’s communist party would not have celebrated a rain of capitalist dollars, or thrown the doors of its second city open to a predatory symbol of US cultural imperialism. But, just as Disney is eager to be in China, China is eager to forge partnerships aimed at expanding its own entertainment reach beyond its borders.

A quarter of a century after the first foreign films were allowed to be shown in China under a strict quota system, the country’s film industry is already on the verge of toppling the US as the world’s number one film market.

And yet Disney’s opening in China takes place as the country is in the midst of a backlash against western values and culture. According to the Chinese military newspaper the People’s Liberation Army Daily, western values such as democracy and freedom of speech were infiltrating China via an unlikely Trojan horse: Disney’s computer-animated movie Zootopia. Set in a city populated by animals in which predators and prey must learn to get along, the film “clearly grasps the spirit of US strategy”, the newspaper reported in April.

“Even though Disney has great appeal to kids, it’s spreading other people’s culture, not our own,” Li Xiusong, deputy head of propaganda in Anhui province, said in March. “This will lead to our kids chasing after western culture at a young age, and when they grow up they will be cold, unfeeling toward Chinese culture.”

Disney has seen its DisneyLife online streaming platform, run under a licence held by the Chinese internet giant Alibaba, shut down earlier this year amid new regulations banning many foreign companies such as Apple from publishing material online in China. Alibaba insists DisneyLife is down due to a “system upgrade”.

Nothing, in short, embodies the love-hate relationship China has for the US quite like Disney does.

According to estimates, Shanghai Disneyland will attract more than 10m people in its first year. But on the opening day the complexities of translating mass culture from the global to the local were underscored by a simple prop in Treasure Cove, the pirate-themed section of the park. There, among a grove of palm trees, lay a wooden box with the label “East India Company” — the company synonymous with the opium war and China’s century of humiliation at the hands of western imperialism — stencilled on to its side.

As Chinese families lined up outside for hours to get inside the park, the box underscored China’s traditionally uneasy relationship with foreign economic interests. Are Disney’s addictive cultural products, its perfect princesses and catchy songs, like a new type of opium? Asked about the box, a Disney representative said only that “Treasure Cove is themed around an 18th-century Caribbean port town and the entire land’s immersive storytelling is consistent with this theme”.

Disney has made much of the concessions it had agreed to come to China. “We didn’t just build Disneyland in China . . . we built China’s Disneyland,” said Iger, Disney’s chief, the day before the grand opening. But the only part of Disneyland Shanghai that feels distinctly Chinese is the food: Mickey Mouse-shaped Peking duck pizzas, along with the usual noodles and Gong Bao Chicken. The “Mainstreet USA” of other Disneys has been renamed “Mickey Avenue”. But it features the same Norman Rockwell-esque barber shops and candy stores with a 1920s small-town America feel. Other Disneys around the world have Space Mountain, but this was not deemed futuristic enough for the Chinese; instead there is Tron Lightcycle Power Run — the fastest rollercoaster built in a Disney theme park. A row of portraits reimagines 12 Disney characters as animals of the Chinese Zodiac. A peony, symbol of Shanghai, adorns the top of the Disney palace, though invisible from a distance. Chinese acrobats perform a Tarzan show. But that’s about it.

In fact, while Disney insists it capitulated to local tastes, it was prepared to do far more but was blocked by the Chinese side, who were more interested in “authentically Disney” than “distinctly Chinese”. According to someone familiar with the protracted negotiations over how to build the park, Disney offered to include more Chinese architectural features in the Disney palace. But market research showed Chinese consumers expected the castle to be a realistic depiction of a European castle. They just wanted the biggest Disney palace, not a Chinese one.

Disneyland Shanghai is not just the largest cross-border entertainment deal in China’s history, but the culmination of an entanglement with the west and its brands that began under Deng Xiaoping, on a par with the first western film import — Warner Bros’ The Fugitive in 1994.

While many people in China are able to celebrate and identify with western brands, they are by turns star-struck and cynical. That was clear in the reception of Disney by locals: the agency YouGov said 44 per cent of the Chinese people they polled planned to visit the park in the first year. But opinions from early visitors have been mixed, seeming to break down along the line of visitors who had been at other foreign theme parks, and those who hadn’t. For those comparing Disney Shanghai to China’s theme parks, the experience was thought to be much better.

“Maybe my hopes were too high but the high-tech rides were a let-down — they were not cutting-edge,” said Tang Jiayi, a 28-year-old who works for a Chinese tech company, before comparing Disneyland Shanghai unfavourably to theme parks abroad.

For the Chinese, Disney is nothing new — most have grown up on Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, or are growing up with Princess Elsa and Anna from Frozen. But Disney is hoping the theme park will cement some of the strong loyalties children have with the brand.

My three-year-old daughter has grown up in Beijing and learned the lyrics to “Let it Go”, from Frozen, along with most of the Beijing resident toddlers she knows. And at her nursery, on the days when toddlers can choose their clothes, there are reliably at least five or so Disney princess dresses in a class of 14 girls. How long will China’s homegrown cartoon characters — among them Pleasant Goat, Big Bear, and a character known as “Bald-Headed Qiang”, who brandishes an Elmer Fudd-style shotgun — last under the Disney onslaught?

Chinese cartoons, even by Wile E Coyote standards, are violent. Pleasant Goat was targeted by broadcast regulators for “excessive violence” in 2013, including boiling alive, assault with a frying pan, and electric shocks. But at Ritan Park, a small amusement park three metro stops from Tiananmen Square and two blocks from my home, these characters come alive, encapsulating the eccentric nuttiness of China’s cartoon world.

There is the Pleasant Goat merry-go-round, and even a “Dishney” bouncy castle. For parents with no hangups about war toys, there is also a merry-go-round of tanks complete with machinegun sound effects, and then there is a character I lovingly refer to as Axe Bunny, a rabbit on horseback wearing a demented grin and waving a bloodstained hatchet.

For Shang Linlin, vice-president of Shenzhen’s Fantawild culture and technology group, which owns China’s second largest group of theme parks and the trademark to Big Bear, Second Bear, and “Bald-Headed Qiang”, all is not lost. Local identification gives his characters their best advantage, he said, adding that all of his characters have regional accents from China’s north-east or Dongbei region. “Beware of Bear digs deep into the culture of Dongbei and in the series there are distinctly Dongbei-style architecture, cuisine, dialect, creating a distinctly Dongbei flavour. It is unique because of this cultural background,” he said.

China’s entertainment industry will increasingly have to survive in an arena that pits the particular against the global. Another competitor to Disney is China’s richest man, Wang Jianlin, with a fortune estimated at $34bn. Wang’s Dalian Wanda conglomerate last month opened Wanda City, a leisure resort in Nanchang, southern China.

Wang is banking on its ability to satisfy local tastes. “The days of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck creating a frenzy are over,” Wang told China Central Television last month. “One tiger is no match for a pack of wolves — Shanghai has one Disney, while Wanda, across the nation, will open 15 to 20 Wanda Cities.”

Nor is Shang of Fantawild fearful. “Disney’s arrival shows that China’s market has great potential. Disney will provide a high-quality, high-standard role model for the industry, and will promote a shift from price competition to quality and brand competition,” he said.

Disney, he continued, comes at a catalytic time for China, while China has come at a catalytic time for Disney. Only 7.5 per cent of Disney’s $52.5bn revenues from its last fiscal year came from Asia, and so it might have to become increasingly Asian if it wants to grow.

With another 60 theme parks set to be built by 2020, including a Universal Studios theme park in 2019, the entire industry will be transformed, and Chinese theme parks will have to improve or face “oblivion”, in the words of Shang.

Richard Huang, of Nomura investment bank in Hong Kong, says China wants its own entertainment industry to be globally competitive, but that means not throwing open the doors of competition too wide.

But it also doesn’t mean shutting them completely. “For all Asian countries the problem is the same. They want the overall market to grow and the quality of domestic products to rise and be competitive abroad. That’s why they need to bring in international competition to uplift the quality. Just not too much international competition.”

For China’s government, the era of social tinkering has not yet ended. But the goals have changed from the days of socialism. In other words, let the “rain of dollars and renminbi” begin.

Charles Clover is the Financial Times’ Beijing correspondent

Additional reporting by Ma Fangjing

Photographs: Matt Stroshane/©Disney; Bloomberg; Barcroft Media

Comments