Amazon unpacked

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Between a sooty power station and a brown canal on the edge of a small English town, there is a building that seems as if it should be somewhere else. An enormous long blue box, it looks like a smear of summer sky on the damp industrial landscape.

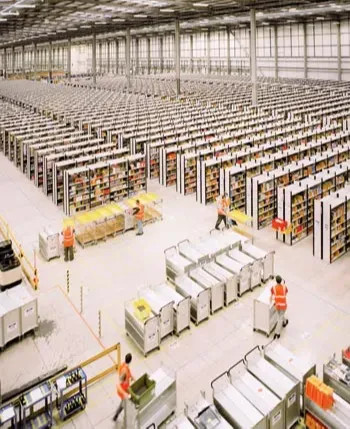

Inside, hundreds of people in orange vests are pushing trolleys around a space the size of nine football pitches, glancing down at the screens of their handheld satnav computers for directions on where to walk next and what to pick up when they get there. They do not dawdle – the devices in their hands are also measuring their productivity in real time. They might each walk between seven and 15 miles today.

It is almost Christmas and the people working in this building, together with those in seven others like it across the country, are dispatching a truck filled with parcels every three minutes or so. Before they can go home at the end of their eight-hour shift, or go to the canteen for their 30-minute break, they must walk through a set of airport-style security scanners to prove they are not stealing anything. They also walk past a life-sized cardboard image of a cheery blonde woman in an orange vest. “This is the best job I have ever had!” says a speech bubble near her head.

If you could slice the world in half right here, you could read the history of this town called Rugeley in the layers. Below the ground are the shafts and tunnels of the coal mine that fed the power station and was once the local economy’s beating heart. Above the ground are the trolleys and computers of Amazon, the global online retailer that has taken its place.

As online shopping explodes in Britain, helping to push traditional retailers such as HMV out of business, more and more jobs are moving from high-street shops into warehouses like this one. Under pressure from politicians and the public over its tax arrangements, Amazon has tried to stress how many jobs it is creating across the country at a time of economic malaise.

The undisputed behemoth of the online retail world has invested more than £1bn in its UK operations and announced last year that it would open another three warehouses over the next two years and create 2,000 more permanent jobs. Amazon even had a quote from David Cameron, the prime minister, in its September press release. “This is great news, not only for those individuals who will find work, but for the UK economy,” he said.

People in Rugeley, Staffordshire, felt exactly the same way in the summer of 2011 when they heard Amazon was going to occupy the empty blue warehouse on the site of the old coal mine. It seemed like this was the town’s chance to reinvent itself after decades of economic decline. But as they have had a taste of its “jobs of the future”, their excitement has died down. Most people are still glad Amazon has come, believing that any sort of work is better than no work at all, but many have been taken aback by the conditions and bitterly disappointed by the insecurity of much of the employment on offer.

If anyone should still be a cheerleader for Amazon, which has created hundreds of jobs in the past 18 months in a community that sorely needs them, it is Glenn Watson, manager of economic development at the district council. But he is dismayed. “They’re not seen as a good employer. It’s not helpful to our economy; it’s not helpful to the individuals,” he says. Britain’s economic transformation is playing out in miniature in this smoky little town. It hasn’t been a smooth ride.

Like almost everyone without a job in Rugeley, a mostly white working-class town of about 22,000, Chris Martin started scouring the internet for application details as soon as he heard Amazon was coming. Local politicians rushed out jubilant press releases. “It’s absolutely fantastic news for Rugeley,” the release from Aidan Burley, the area’s member of parliament, said. “People are crying out to get back into work.”

Rugeley had never fully recovered from the mine’s closure in 1990, and the local economy was further depleted by Britain’s deep recession of 2008-09. Chris Martin moved there in 2007 to be with his partner. “She led me a merry story, saying, ‘Oh you should walk into a job,’ but there’s no jobs down here,” he said ruefully. The 54 year-old found a night job filling shelves in the Morrison’s supermarket for a while, but it didn’t last. It didn’t help that he was a relative newcomer in this close-knit community, where job opportunities often spread by word of mouth. “Nearly everybody knows everybody else. If you come from outside it’s like walking into a bar in a western,” he said. “Everyone stares.”

So Martin was thrilled when he passed the Amazon recruitment process, which includes drug and alcohol tests, and was given a job on the night shift. A global employment agency called Randstad, which had handled the recruitment process for Amazon, was also to arrange his shifts, manage him on the warehouse floor and pay him his near-minimum wage. After three months, if he had performed well, he could apply to be an Amazon employee, though there was no guarantee he would succeed. Randstad calls this sort of system “Inhouse Services” and describes it as a “flexible work solution designed exclusively for each client to optimise the work force and drive cost effectiveness”. One of the benefits for clients, it says on its website, is the “removal of the administrative burden of recruiting and managing large numbers of staff”.

There was an electric atmosphere in the big blue warehouse that autumn as the operation geared up for the first time. “At the start it was buzzing,” said a member of the Amazon management team at the site, who did not want to be named. “Brothers, sisters, neighbours, everyone was just so pleased to have jobs. Everything was new.”

Workers in Amazon’s warehouses – or “associates in Amazon’s fulfilment centres” as the company would put it – are divided into four main groups. There are the people on the “receive lines” and the “pack lines”: they either unpack, check and scan every product arriving from around the world, or they pack up customers’ orders at the other end of the process. Another group stows away suppliers’ products somewhere in the warehouse.

They put things wherever there’s a free space – in Rugeley, there are inflatable palm trees next to milk frothers and protein powder next to kettles. Only Amazon’s vast computer brain knows where everything is, because the workers use their handheld computers to scan both the item they are stowing away and a barcode on the spot on the shelf where they put it.

The last group, the “pickers”, push trolleys around and pick out customers’ orders from the aisles. Amazon’s software calculates the most efficient walking route to collect all the items to fill a trolley, and then simply directs the worker from one shelf space to the next via instructions on the screen of the handheld satnav device. Even with these efficient routes, there’s a lot of walking. One of the new Rugeley “pickers” lost almost half a stone in his first three shifts. “You’re sort of like a robot, but in human form,” said the Amazon manager. “It’s human automation, if you like.” Amazon recently bought a robot company, but says it still expects to keep plenty of humans around because they are so much better at coping with the vast array of differently shaped products the company sells.

The unassuming efficiency of these warehouses is what enables Amazon to put parcels on customers’ doorsteps so quickly, even when it is receiving 35 orders a second. Every warehouse has its own “continuous improvement manager” who uses “kaizen” techniques pioneered by Japanese car company Toyota to improve productivity. Marc Onetto, the senior vice-president of worldwide operations, told a business school class at the University of Virginia a few years ago: “We use a bunch of Japanese guys, they are not consultants, they are insultants, they are really not nice … They’re samurais, the real last samurais, the guys from the Toyota plants.”

In Rugeley, the person with the kaizen job is a friendly, bald man called Matt Pedersen, who has a “black belt” in “Six Sigma”, the Motorola-developed method of operational improvement, most famously embraced by Jack Welch at General Electric. Every day, the managers in Rugeley take a “genba walk”, which roughly means “go to the place” in Japanese, Pedersen says as he accompanies the FT on a tour of the warehouse. “We go to the associates and find out what’s stopping them from performing today, how we can make their day better.” Some people also patrol the warehouse pushing tall little desks on wheels with laptops on them – they are “mobile problem solvers” looking for any hitches that could be slowing down the operation.

…

What did the people of Rugeley make of all this? For many, it has been a culture shock. “The feedback we’re getting is it’s like being in a slave camp,” said Brian Garner, the dapper chairman of the Lea Hall Miners Welfare Centre and Social Club, still a popular drinking spot.

One of the first complaints to spread through the town was that employees were getting blisters from the safety boots some were given to wear, which workers said were either too cheap or the wrong sizes. One former shop-floor manager, who did not want to be named, said he always told new workers to smear their bare feet with Vaseline. “Then put your socks on and your boots on, because I know for a fact these boots are going to rub and cause blisters and sores.”

Others found the pressure intense. Several former workers said the handheld computers, which look like clunky scientific calculators with handles and big screens, gave them a real-time indication of whether they were running behind or ahead of their target and by how much. Managers could also send text messages to these devices to tell workers to speed up, they said. “People were constantly warned about talking to one another by the management, who were keen to eliminate any form of time-wasting,” one former worker added.

In a statement, Amazon said: “Some of the positions in our fulfilment centres are indeed physically demanding, and some associates may log between seven and 15 miles walking per shift. We are clear about this in our job postings and during the screening process and, in fact, many associates seek these positions as they enjoy the active nature of the work. Like most companies, we have performance expectations for every Amazon employee – managers, software developers, site merchandisers and fulfilment centre associates – and we measure actual performance against those expectations.”

The former shop-floor manager and another worker described a strict “three strikes and release” discipline system – “release” being a euphemism for getting sacked. In the early days, people were “released” frequently and with little warning or explanation, workers said. A very large number were laid off after the first busy Christmas period, some of whom had assumed their jobs would be permanent. Chris Martin says his job lasted less than a week after he took a day off for blisters and returned to find the night shift he was on had been abruptly cancelled.

It is this job insecurity that has most disappointed Glenn Watson at the district council. “Our definition of a good employer is someone who takes on people and provides them with sustainable employment week in week out, not somebody who takes on workers one week and gets rid of them the next,” he said. The council had understood Amazon would use the first 12 months to gradually build up its own workforce, transferring agency staff on to its payroll, but by last autumn Watson thought there were still only about 200 Amazon employees, with the rest of the workers supplied by Randstad and two smaller agencies. One young man strolling out of the warehouse last September said he was still an agency worker, even though he had been there since the site opened.

Watson said Amazon was supposed to send the council employment data every six months, but it had not done so. “We had no idea Amazon were going to be as indifferent to these issues as they have been, it’s come as a shock to us how intransigent they are,” he said.

Inside the warehouse, Amazon employees wear blue badges and the workers supplied by the agencies wear green badges. In the most basic roles they perform the same tasks as each other for the same pay of £6.20 an hour or so (the minimum adult wage is £6.19), but the Amazon workers also receive a pension and shares. A former agency worker said the prospect of winning a blue badge, “like a carrot, was dangled constantly in front of us by management in return for meeting shift targets”. Amazon’s Darwinian culture comes from the top. Jeff Bezos, its chief executive, told Forbes magazine last year (when it named him “number one CEO in America”): “Our culture is friendly and intense, but if push comes to shove, we’ll settle for intense.”

Chris Forde, a professor of employment studies at Leeds university, says arrangements such as Randstad’s with Amazon are becoming increasingly common in Britain. He has encountered situations in which workers on these sorts of contracts make up 90 per cent of a company’s workforce in sectors such as car manufacturing, food processing, hotels and restaurants. “The message [from the agencies] is we are a key intermediary and we can help people back into work, but I think the danger with these big contracts, which are now the bread and butter of most big agencies, is that people just get stuck in these jobs.” Across Britain, the number of people in temporary jobs has swelled 20 per cent since the financial crisis hit in 2008, and the proportion of that group who say they cannot find permanent jobs has increased from 26 per cent to 40 per cent.

Amazon said it employed “hundreds of permanent and temporary associates” at Rugeley and had recently given a further 200 permanent jobs to temporary workers there. It said it was proud of giving its “associates” a “great working environment”, including on-the-job training, opportunities for career progression, competitive wages, performance-related pay, stock grants, healthcare, a pension plan, life assurance, income protection and an employee discount. It added: “In order to ensure that we are providing our customers [with] the highest level of service, we do take on temporary associates during periods of high demand. When we have permanent positions available, we look to the top performing temporary associates to fill them.”

The total size of Amazon’s workforce in the UK is hard to pin down and it changes dramatically depending on the time of year. Late last year, an Amazon official told a parliamentary committee the company employed about 15,000 people. In October last year, Amazon issued a press release saying it was about to take on 10,000 temporary workers to deal with the Christmas rush. In the company’s 2011 UK accounts, it said its average number of employees was 3,023.

Randstad said it supplied a number of clients with “onsite-flexible workforce solutions”. It added: “The number of workers required by these clients fluctuates in response to supply and demand. When demand for clients’ products or services is high (for example during the Christmas period) the Randstad partnership allows local people to benefit from short-term work on a temporary contract, to help supplement our clients’ permanent workforce and deliver against order requirements.”

Certainly, not everyone in Rugeley is upset about Amazon. A group of workers having a pint on a picnic table outside The Colliers pub near the warehouse gates said they liked their jobs, albeit as their managers hovered nervously in the background. One young agency worker said he was earning about £220 a week, compared with the £54 he had been receiving in jobless benefits. He had bought a car and moved out of his mum’s house and into a rented flat with his girlfriend, who he had met at work. “I’m doing pretty well for myself,” he said with a shy grin. “There’s always opportunities to improve yourself there.” Across the table, an older man, wagging two fingers with a cigarette pinched between them, said slowly: “It gives you your pride back, that’s what it gives you. Your pride back.”

Many in the town, however, have mixed feelings. They are grateful for the jobs Amazon has created but they are also sad and angry about the quality of them. Timothy Jones, a barrister and parish councillor, summed up the mood. “I very much want them to stay, but equally I would like some of the worst employment practices to end.”

For Watson, the big question is whether these new jobs can support sustainable economic growth. In Rugeley, it is hard not to look back to the coal mine for an example of how one big employer could transform a place.

…

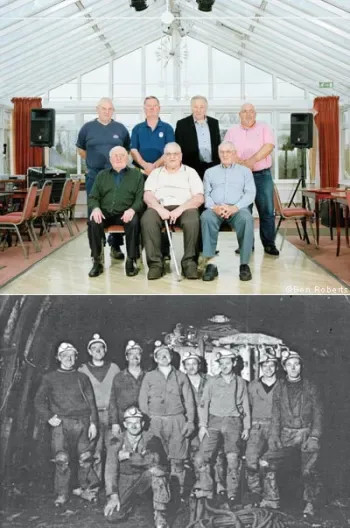

The Lea Hall Colliery opened officially on a soggy Tuesday in July 1960. Miners and their families huddled under marquees to eat their packed lunches and when the first coal was wound to the surface, three bands played an overture specially written for the occasion. It was the first mine planned and sunk by the Coal Board, the body set up after the second world war to run Britain’s newly nationalised coal industry, and the Central Electricity Generating Board was building a coal-fired power station right next door. It was a defiant demonstration of confidence in coal at a time of increasing competition from oil. “King Coal is not yet dead, as many would have it, but is going to be with us for many years to come,” the regional secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers told the crowd.

Soon, miners from all over the country were swarming to the modern new mine. The Coal Board and the local council built housing estates and schools to cope with the exploding population. “Peartree estate was built for the Geordies, the Springfield estate was built for the Scots and the Welsh,” remembered Brian Garner, who helped to build the mine when he was 16. “It was unbelievable, it was buzzing in the town, there was that much money about then. I could leave my job at 10 o’clock in the morning and start at five past 10 on another.” On Friday and Saturday nights, the queue outside the Lea Hall Miners’ Welfare Centre and Social Club would wrap right around the building.

Rugeley’s mine was soon the most productive in the country. It was a “young man’s pit” with all the latest machines and techniques, says Ken Edwards, who started there at 25 as an electrician. The work was still dirty and dangerous, though. In 1972, a local reporter took a tour. “All is silent except for the movement of conveyor belts which carry the coal and the murmur of the air pumps. The blackness is relieved only by narrow shafts of light coming from each person’s headlamp,” she wrote. It took her two days to remove the black dust from her nails, ears, nose and hair.

The good times didn’t last. By the time the pit closed, four days before Christmas in 1990, a spokesman for British Coal told Reuters it was losing £300,000 a week. More than 800 people lost jobs that paid the equivalent of between £380 and £900 a week in today’s money. The town council’s chairman tried desperately to say something reassuring. “It has come as such a shock,” he told the local paper. “[But] we have got to do what many have done and look for new areas, particularly information technology and high technology. We have a lot of expertise and a wonderful geographical spot. There’s no reason why it should be the end for Rugeley.”

From behind her desk in Vision estate agents, all purple paint and fairy lights, Dawn Goodwin sucks the air in through her teeth at the mention of Amazon. “We all thought it was going to be the making of the town,” she says. She expected an influx of people, including well-to-do managers, looking to buy or rent houses. But she hasn’t had any extra business at all. People are cautious because they don’t know how long their agency jobs with Amazon will last, she says. One of her tenants, a single young woman, got a job there but lost it again after she became ill halfway through a shift.

She struggled to pay her rent for three months while she waited for her jobseeker’s benefits to be reinstated. “It’s leaving a bad taste in everyone’s mouths,” Goodwin says with a frown. Even the little “Unit 9” café next to the Amazon warehouse hasn’t had a boost in trade. The women who run it reckon the employees don’t have enough time in their 30-minute break to get through security, come and eat something, and then go back in again.

In a cramped upstairs office at the Citizens Advice Bureau, Gillian Astbury and Angela Jones have turned to statistics to try to identify Amazon’s effect on the area. They haven’t had an increase in the number of people asking about employment problems or unfair dismissal, but nor has there been any improvement in the community’s problems with debt and homelessness. Their best guess is that people haven’t had enough sustained work to make much of a difference.

Astbury says employment agencies are a “necessary evil”, but stresses it is hardly ideal for people to be bouncing in and out of temporary work, particularly when a job ends abruptly and they are left with no income at all until their benefits are reinstated. Workers leaving Amazon have had a particular problem with this, prompting the parish council to submit a Freedom of Information request to the Department for Work and Pensions to find out exactly how long local people are being made to wait for their social security payments to come through.

Far from the CAB’s little office in Rugeley, Britain’s economists are also puzzling over why the economy remains moribund even though more and more people are in work. There are still about half a million fewer people working as full-time employees than there were before the 2008 crash, but the number of people in some sort of employment has surpassed the previous peak. Economists think the rise in insecure temporary, self-employed and part-time work, while a testament to the British labour market’s flexibility, helps to explain why economic growth remains elusive.

Angi Cooney, who runs C Residential, the biggest estate agent in Rugeley, thinks the nature of employment is changing permanently and people should stop pining for the past. It’s “bloody great” that a company like Amazon chose to come to “this little old place”, she says fiercely, looking as if she’d like to take the town by the shoulders and give it a shake. “People expect a job for life, but the world isn’t like that any more, is it?”

Sarah O’Connor is the FT’s economics correspondent

Comments