Def Con: the ‘Olympics of hacking’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When tens of thousands of computer hackers hit Las Vegas for a weekend, a drab convention centre is transformed for a very different kind of conference. There are no monotonous PowerPoint presentations or “networking breaks” here. Instead, hackers are bent double over tables, busily dissecting hard drives and picking locks; others huddle in a dark and cavernous room showing off their skills by breaking into each other’s computers. Almost all are making mischief until dawn.

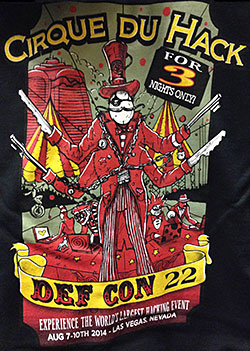

Welcome to Def Con, the Olympics of hacking, where for 21 years computer hackers have been gathering to compete, share their knowledge and, perhaps most of all, meet like-minded people in the real, offline world. A festival atmosphere fills the hallways as delegates greet old friends, addressing each other by online nicknames.

Def Con attracts thousands of the world’s top hackers, those who aim to seek out weaknesses in computers and networks that can be used to steal data or take down websites. Many are “white hat”, meaning they discover the flaws in order to fix them and improve security; others are “black hat”, using their skills to commit crime. A few fall in the grey area in between.

The vast majority of hackers are obsessively curious people who are driven to find out how things can be broken so they can design ways to better protect them. Often wrongly maligned by the outside world, this is a distinct community – one that has its own culture, which members are eager to preserve even as the number of security professionals grows rapidly and multinationals and governments seek out their expertise.

…

Def Con began in 1993 when a group of about 100 bedroom hackers (who communicated over bulletin boards) decided to meet in Las Vegas. They were part of the generation depicted in WarGames, the 1983 film about a youngster who finds a back door into a military computer while messing around on his computer.

In those early days there was a dedicated squad of attendees who ran into other guests’ hotel rooms to jump on their beds, as well as a conference “3-2-1 rule” that dictated everyone should try to get three hours of sleep, two meals and one shower each day. During the first years, I am told, poorly disguised men from the intelligence services turned up, leading to a “spot the fed competition” where people who looked as if they could be government agents (often those wearing polo shirts and penny loafers) were called out in public.

After decades of being regarded with suspicion, many hackers prefer to use nicknames and others choose not to talk to outsiders at all. Def Con allows people to be as anonymous as they want. “Dead Addict”, who was at the first event and is still a regular, tells me people first came to Def Con out of “raw passion . . . The hackers were hobbyists. They were breaking the law but it wasn’t criminal enterprise for profit,” he says as he sits at a table in the corner of the conference room wearing his trademark bowler hat. According to Dead Addict, the atmosphere has changed with the “professionalisation of cyber crime”.

As the commercial world has moved online, so, too, have organised criminals and well-funded nation states. The threat from cyber crime has soared in the past five years as we spend more of our lives, and our money, online. In the 1990s, law enforcement agencies saw teenage hackers as the problem. Now they struggle to defend consumers, companies and countries against the likes of Russian gangs and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Earlier this year, the US government issued “wanted” posters for Chinese cyber criminals as it steps up a diplomatic fight over the cyber espionage that security companies say China has been conducting for years.

A considerable industry has grown up to try to protect against attacks. Experts in defeating cyber security systems, hackers who had learnt their skills for fun found themselves courted by corporations. So this year, though the conference floor is still filled with scruffy, bearded hackers looking like outsiders, many run their own businesses or are senior security managers for some of the world’s largest companies.

Marc Rogers is one of the few people happy to give his real name. At Def Con he is known as CJ, short for “Cyber Junky”, and acts as head of security for the conference. In his day job he is principal security researcher for Lookout, a mobile security start-up in San Francisco. Def Con, Rogers says, has grown into a “huge behemoth” with an estimated 17,000 delegates. The exact number of attendees is unknown – everyone pays cash on the door and no attendance records are kept for fear they will be subpoenaed by law enforcement agencies searching for suspects in computer crime cases.

Rogers recalls that “there were just a few hundred folks at the first one I went to, at Def Con 6 [1998]. It was just a bunch of guys hanging out and swapping stories, with crazy high jinks like reprogramming the hotel elevators or the pbx system [internal phone network].

“Over the years we’ve sort of grown up. The security industry is such an important part of the financial system, now everyone is earning quite a significant amount of money.”

The event has also become a kind of alternative recruitment fair. “There are different tricks to try and recruit folks that everyone from government agencies through to big corporations and even the mafia have used,” Rogers says. “There was a famous party at Def Con 11 when some very suspicious guys hired quite a significant amount of hotel casino space and invited people to come party. It was pretty clear they were the criminal underground looking for sources.”

…

The dramatic transformation of hackers from the hunted to the hunters happened in the mid-2000s when governments and companies realised they desperately needed these skills – and it was tricky to train people to be inquisitive in quite the right way.

Marc Maiffret is one of the older generation who started off by experimenting with hacking on the borders of illegality but ended up entering a very lucrative business. Maiffret, now chief technology officer of the security company Beyond Trust, was raided by the FBI when he was 17. Just three years later he was selling his product to the US defence department.

Def Con brings hackers into contact with people they can trust. This is vital in a community where many have skills they could use to do great harm – and where the battle against cyber crime needs co-operation from people with different kinds of security expertise. Def Con may look like a high-tech theme park – “spring break for hackers”, as one attendee says – but it is an important way of inculcating a new generation in community ethos. Some principles are clear: sharing knowledge through open-source software is good, invading people’s privacy or compromising civil liberties is bad.

“There’s a fear that the outside world is starting to become a part of hacker culture,” Rogers says. “It is being industrialised at quite a ferocious rate. More and more we’re seeing folks in suits, some are hackers grown up, some are university graduates who took security as a BA.”

At the opening ceremony, hundreds of people crammed into the conference centre’s largest auditorium. Def Con founder Jeff Moss, known as “Dark Tangent” or DT, ran through the audience to the stage, late to his own event. Outside Def Con, he has worked as chief security officer for the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, a non-profit that co-ordinates internet security and stability, and is an adviser to the US Department for Homeland Security.

In a seemingly off-the-cuff speech, Moss explained that, despite the slight air of disorder, he did not want Def Con to take corporate sponsorship. “We don’t care if we’re corporate-friendly,” he said. “That would be really great to get money from sponsors but then they would ask to speak. I want to avoid all those problems because I think we don’t want to worry about a hidden agenda.”

The vendor hall at Def Con is only the size of two tennis courts (tiny by conference standards) and dominated by stands selling servers, lock picks and T-shirts with “hack naked” printed on them. The most corporate stand, where carmaker Tesla is inviting people to scrutinise the security of its smart cars, is relegated to a distant corner of the room.

Def Con costs just over $200 to attend, far less than most cyber security conferences, because it is run by a small army of volunteers, known as “goons”. (Black Hat, a more business-focused security conference that took place in Vegas in the few days beforehand, charged more than $2,000.) Some people attend both conferences, switching from suits at Black Hat to T-shirts at Def Con.

Some of the companies attending Def Con are glad it is trying to resist corporatisation. Joe Sullivan, Facebook’s chief security officer, first came five years ago. He brings about 20 of the company’s security engineers, and Facebook funds 10 scholarships for students to attend the event.

Sullivan thinks it is important that Def Con remains an informal place where hackers learn from each other, rather than turning into a market for security products. “When you do security, you want to talk to other people about security – you don’t want to have vendors who are trying to sell you stuff,” he says. “I don’t think deals or transactions are done here – it is a place people can say, ‘We’re having this headache now.’ ”

In past years Facebook has launched high-profile security programmes at Def Con, such as “bug bounties”, with rewards for finding vulnerabilities in the site. The programme paid out $1.5m in bounties in 2013, spread between 330 researchers.

For a new generation of hackers, some of the attraction of going into the security business is the chance to make big money. One “n00b”, as new attendees at Def Con are called, talks to me while he is hungover from a night of partying. He’s hiding under an oversized yellow T-shirt and behind a blank look. “I guess I like the money. I was a programmer – I like to do that – so, if you add the security, you make more money.”

Many of the older hackers I speak to worry this new generation faces much harder ethical dilemmas. They fear hackers could easily be led astray – whether it be selling their skills on underground marketplaces to criminals, or, after the National Security Agency revelations, using them to spy on the mass population. Maiffret, for example, says: “I was into the exploration of systems, seeing what I could do – not stealing financial data or stuff. These days there is a link to organised crime and profit. Who knows what I would have fallen in to?”

The security services have long tried to use Def Con as “one big old recruitment fair”, says Zac Franken, who ran operations for Def Con for 20 years. General Keith Alexander, then director of the NSA, spoke at the conference in 2012. Since the Edward Snowden leaks, the community is now more worried about the expansion of surveillance. Franken says: “I think we were always very aware of what the NSA was doing and capable of but I think we were slightly complacent about it, always assumed a big government organisation was probably not very good at it.

“What the Snowden revelations have shown is that they are, in fact, extremely good at it – they have created a virtual panopticon.”

…

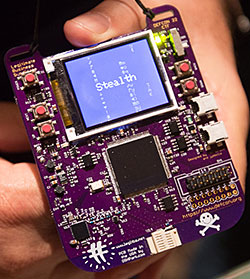

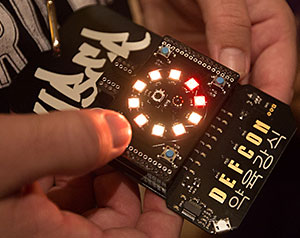

The best way to mentor new hackers is to teach them the community’s cultural values at the same time as skills. At Def Con, one of the ways they do that is through a team competition devised by “LosT”, a bearded man fond of wearing a black hat. He creates a complex contest around the conference badges every year, challenging attendees to decrypt the often electronic badges that lead them through a web of code, cultural clues and different kinds of security. He deliberately designs his head-scratchingly hard competition to bring the generations closer together. Among this year’s clues, which include everything from computer code to weaving the conference lanyards together in a pattern that reveals a medieval numbering system, are references to rotary dials on telephones and the TV show Frasier (1993-2004).

“At one point a group close to winning the competition googled down a rabbit hole in the wrong direction,” LosT says. “I stopped them and asked, ‘How old are you?’ He said 25, and the other people on the team were about the same age. I said, ‘Go and find someone over the age of 35.’ Then they got it and it was purely a generational thing. Google didn’t help.”

This year it took three days for a winner to be declared. The prize is a black badge that guarantees free entrance to Def Con for life, and the winning team includes both old-timers and a couple of younger hackers, who have pulled in help from people around the world, via Skype.

Some delegates are setting their sights on an even younger generation. Nico Sell, chief executive of Wickr, a platform and app that allows users to send secure, encrypted and time-limited messages, counts the CME Group, the world’s largest futures exchange, among her investors. She has been helping organise Def Con for years and now runs r00tz Asylum, a non-profit organisation that teaches children to become “white hat” hackers.

Taking over a theatre space at the conference, she invites the most expert hackers in the world to share their knowledge with children as young as five. Employees from Google and AT&T have stalls where they teach hacking.

Muffenboy, who is 10, is preparing to give a Def Con speech on how to overcome hacker stereotypes. “People think hackers are all bad and evil but that’s far from the truth,” he says. He has programmed his own operating system and has a YouTube channel with technology videos he makes.

Kryptina, 12, who won five hacking contests at last year’s Def Con, says: “It is really fun to do activities like lock picking and hardware hacking with all these crazy people where no one is judged.”

Sell, like many other Def Con devotees, prizes the “ethical moral structure” of hackers above all else. “It is really a community, you don’t succeed as a hacker unless you are trusted and have integrity.”

“This is how you get people into stuff, how you change society, by making it an art and a game,” she says.

——————————————-

Images from Def Con 22, which took place in Las Vegas from August 7 to 10 2014. Photographs: Dave Bullock

Hannah Kuchler is an FT San Francisco correspondent

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Harassment rife at hacker conference / From Ms Emily E Reid

Comments