Working older

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It is difficult to hear Tim Hulse. The café in the centre of Chester, northwest England, close to where he lives, is full of chattering mothers and their screechy young charges. Over the din, Hulse announces with a smile that today is his birthday. He is 54.

Dressed in black fleece and jeans, Hulse has a youthful demeanour: poised and straight-backed. He regularly runs half-marathons, claiming to do so far quicker than many 20-year-olds he knows. Later today he will celebrate with his wife and six-year-old son. “Fifty is the new 30,” he grins, aware the mantra has become a cliché.

A few years ago, that notion might not have raised a smile. At the age of 49, Hulse felt he was on the scrap heap. In 2011, after a career selling software to banks, he was laid off by the company where he had worked for almost nine years. A 23-year-old graduate was put in his place, at a fraction of the price. “Overskilled” and “expensive” were reasons he was given. But to Hulse these were just polite euphemisms for “old”.

“It’s a real punch in your guts,” he says. “Everything I’d done counted for nothing. It all evaporated. The biggest deal I did was $34m. I had managed a team of 50 people — you couldn’t imagine someone out of university able to do that. I thought I was more able to do my job because of my age.”

When it came, redundancy was swift. “It’s still a shock — but I should have known,” he reflects. After the news was delivered, Hulse switched into autopilot. “It was about 4 o’clock. I went back to my desk, quietly put my stuff in a bag and said, ‘See you tomorrow.’” To this day he has never seen any of his former co-workers again.

“Depressed” is a term that gets misused but Hulse says it was accurate in his case. “In hindsight, I was difficult to live with. My wife felt I was depressed for quite some time. You don’t see what’s going on around you, you don’t notice the weather or the view out of the window.” There was embarrassment too. “I didn’t want to show my face in London again. All of my friends were people I worked with. I didn’t have friends in Chester, I was never here.”

Career underpinned his identity. He and his wife had delayed having children so that they could focus on work. “It wasn’t about the money. I like winning. I was focused on getting the sale.” The money was good though — a six-figure base salary (matched by a bonus) which gave him a nice car (a Porsche, since sold) and house.

Hulse had witnessed boom-and-bust cycles before. So when the cost-cutting hit his company, he believed that at his age he was unlikely to find a comparable job. He had observed what happened to the over-fifties in his sector: they tended to tread water, picking up small jobs at small firms. But with a young son and the likelihood he will live longer than his parents, Hulse wanted stimulating work for decades. Fortunately he had a back-up plan.

Work until 70

The longevity revolution is often discussed in terms of the burden of social care and pensions, but it is also having a profound effect on working lives. People today are expected to work longer than they did a generation ago, in step with their elongated lifespans and as stretching out retirement savings becomes more difficult. Today’s fifty and sixtysomethings are at the vanguard, configuring careers they hope will last longer than their parents’. How to sustain a career until 70 will become a pressing issue.

Yet as Hulse shows, it is not straightforward. Some employers characterise workers even in their fifties, let alone their sixties, as expensive, inflexible, out of touch, technologically illiterate and coasting to retirement. Men may feel vulnerable, having historically been prone to defining themselves by their work, but women do too. The Commission on Older Women found that this is a group that may feel doubly discriminated against on age and gender grounds, described as “older earlier”.

If you lose your job after 50, it can be difficult to find a permanent position. The rules are clear — recruiters cannot demand a thirtysomething candidate. But they do not have to be explicit. They can deduce a potential hire’s age from their CV or LinkedIn profile. “Once you get past 50 it’s quite difficult to get a job,” says Malcolm Small, a senior adviser at the Institute of Directors. “[But] no employer will say that.” This is why he recommends a portfolio of contracts.

Amanda Fone, of F1 recruitment, catering to the PR and marketing industries, puts it like this. “Is there discrimination? Of course there is.” The topic is “taboo”, she says. “If you’re over 50 and not a managing director you’re past it in an employer’s eyes.” Interviewers tell her that candidates have too much experience. “How can you be too experienced?” she asks, incredulous.

Baroness Ros Altmann, the government’s former business champion for older workers, now pensions minister, said in a report published in March: “Age discrimination and unconscious bias remain widespread problems.”

Yet this is just part of the picture. There are also solid grounds for optimism. The employment rate for 50-64-year-olds in the UK has risen from 57 per cent in 1995 to 69.4 per cent now, faster than any other age group according to the Office for National Statistics (although you are still more likely to be working if you are in your thirties or forties). This follows age discrimination legislation and the removal of the default retirement age. Some companies have even started to make special efforts to employ older workers. Barclays is extending its apprenticeship scheme for the long-term unemployed to the over-fifties. Others offer mid-career reviews, flexible work and training.

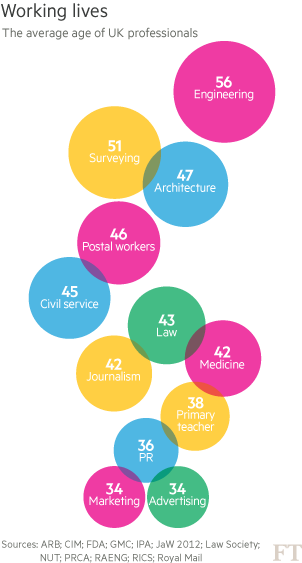

Age discrimination is uneven. One banker told me: “The City has an age bias. You simply cannot have been a very good trader if you have not made enough money to leave by 50.” It follows therefore that “you can’t be a 50-year-old trader”. But while some industries worship the cult of youth, others are agnostic.

This new generation of men and women working for longer needs new skills and attitudes. Often, the solution is to work for themselves. Data released by the ONS last year showed that self-employed workers tend to be older than employees, with 43 per cent of those self-employed being aged 50 and over, compared with 27 per cent of employees.

Managerial occupations including roles within property, marketing and finance have seen the largest rise in self-employment over the past five years. For some, there are new sources of support available. Google has pledged to help first-time entrepreneurs aged over 50.

But if employers are adapting to the over-fifties, they are rarely geared to the over-65s. Moreover, individuals fail to plan for elongated careers. The over-65s’ employment rate may have increased — from 5.2 per cent in 1995 to 10.4 per cent now — but “it needs to speed up”, says Rachel Saunders, director of Age at Work for Business in the Community, a non-profit group.

Hope and fear

Many fiftysomethings are optimistic about their future career development. Trevor Borthwick, 52, partner at Allen & Overy, heads up the law firm’s global corporate lending group. He believes society is changing and so are employers. “Sixty is not considered old any more. The real question is not how old you are but how much enthusiasm you have. I’d worry more if I wasn’t putting enough into the business [than how old I am].” Some might shift into a different career or mix of work.

Mick Jagger should inspire older people to ‘reboot’ their careers, says former minister Esther McVey

Yet others feel vulnerable, that their work is precarious. John is an advertising executive who now travels the world on contract assignments. I talk to him by phone and email when he has downtime in various cities in Australia and Europe. John has worked on vast campaigns and overseen global events but is unable to find permanent employment. Scratch the veneer of ebullience and can-do attitude and there is anxiety: the unending, pit-of-your-stomach variety. John, who does not want to use his real name for fear of blighting his prospects, has never felt like this before.

“When you speak to recruitment agencies they automatically assume you are looking for top income or director-level positions; employers are much the same,” he says. “Everyone wants to pigeonhole you.” His children have left home and he no longer seeks a six-figure salary. Titles are meaningless to him now. “It is quite depressing when you have [gained] a reputation for great work over many years to struggle to even get an interview because people assume you are a threat or want a huge wage. We are comfortable in our skin,” he says. But he does not get the chances: instead he moves from contract to contract.

Hiring bias

When age discrimination hits the courts it can be difficult. Tony Shiret, a former star banking analyst, was once dubbed the “godfather of retail” in the City for his coverage of the sector. In 2013, he won an age discrimination case against his former employer, Credit Suisse. Chosen for redundancy in 2011, after 18 years at the bank, at the age of 55, Shiret, who earned a basic salary of £350,000 a year, was the oldest member of his team.

In the ruling, the employment judge Jill Brown said that because of his age, he was seen as “having no potential, despite his excellent skills and unrivalled contacts”.

Emails between his managers revealed they had discussed “knifing Tony” and that he “isn’t going to be around forever”. Statistics used in the case showed that in 2011, 5 per cent of those under 30 were made redundant. For those between 30-34 it was 11 per cent; 45-49, it was 26 per cent and 37 per cent for those above 50. Only 2 per cent of employees were over 50.

When Shiret had got laid off he was “numb and angry”, he says. The “unfairness compounded the shock. I felt disoriented”. The decision to go to court was difficult. It would have been impossible without the support of his wife and the reserve of funds he had saved over years of bonuses. Why did he do it? “Because I didn’t want to be taken out to the back and shot, quietly.”

Recourse to the courts, he says, is not feasible for most people. “I was financially secure but for lots of people it’s not an option.”

Yet despite his personal experience at work, he believes the biggest problem is hiring. “There is no clear protection from discrimination in recruitment. It may be expensive and a difficult process but the law does at least try to protect you when you have been employed.” In two years, he had only one interview with a global top-tier bank.

Today he is working for the Haitong Securities-owned Banco Espírito Santo de Investimento. He does not see his age as a barrier. “There’s no reason why people can’t carry on doing the job they’ve been doing. It can be physically punishing — being in at 6.30am can be a drain — but the actual age isn’t of itself important.” His motivation, he says, is as fierce as ever. “To think you don’t have the drive any more is rubbish — I know people of 30 I’d sack.”

‘Refirement’

The government wants people to extend their working lives because it can no longer afford pensions for a population that is living longer. The latest data from the ONS predict that about one in three babies born in the UK today will celebrate their 100th birthday. From 2018, the age when citizens can receive a state pension starts to rise to 66 and then to 67 from 2026. In 2013, George Osborne, chancellor of the exchequer, announced intentions to lift the state pension age at a pace that will see young people entering the workforce today not qualify until they are 70.

The UK is not alone. In the US, the age at which one could draw a full state pension is already 66 and set to rise to 67. Denmark, Italy and South Korea, among others, have also opted to link increases in pension ages to changes in life expectancy.

Carlos Slim, telecoms billionaire, says working lives could continue to 75 by putting employees on a three-day week

It is not simply about stemming welfare costs. Keeping older people in work may boost the economy. A report by the think-tank the International Longevity Centre-UK estimated Britain’s gross domestic product could rise by 12 per cent by 2037, assuming continued high migration, if the number of people over 65 in work continues to grow in line with the long-term trend. Consigning older workers to their sofas means the workforce loses valuable expertise.

Sam Pease is the managing director at New Directions. Based in Boston, Massachusetts, it charges senior executives in their fifties and sixties up to $40,000 to assess the next phase in their working life. Most companies, he says, do not invest in training their older employees. Consequently, what happens is that they cling on to their old skills or job because no one helps them figure out an alternative. “People hinder those below them if they feel anxious about their future,” he says.

“Large numbers of older workers have ambitions to improve skills and progress their career. The common perceptions are that there will be cognitive decline and they want to retire,” notes Christopher Brooks, senior policy manager at the charity Age UK.

Workplace attitudes crystallise the broader public debate. Youth unemployment is a huge concern — in the UK the unemployment rate for 16-24-year-olds is 16.1 per cent compared to the headline rate of 5.5 per cent. However, the anxiety that by encouraging older people to work the young will lose out is dismissed by economists as the “lump of labour fallacy”. There is no fixed number of jobs — the OECD has found that countries with higher workforce participation rates at older ages also have them at younger ages.

Older workers are not unique to the UK: Japan has been grappling with this issue for some time. Many Japanese skirt retirement, working to their late sixties. In the US, there is the “encore career” movement, whereby people in their fifties or sixties switch to a new career, perhaps scaling back their outgoings and shifting from private to public sector in order to give something back to society.

For many older people, like New York-based Rosalind Gordon, work provides a purpose and social function. The lawyer was made redundant in 2012 from Pitney Bowes, the US mail systems company. She knew it was coming. When attending an HR meeting to discuss redundancy plans, she turned to the person next to her and said, “I won’t survive this.” Nonetheless, when it came it was still a shock. “I was told by recruiters I wouldn’t get another job at my age.” She was 70.

Gordon dabbled in retirement, took a few family holidays and gave her services to an advocacy group for free. But “it didn’t occupy me enough”, she says. “They don’t take you seriously when they’re not paying you.” Then her severance pay started running out. “I was bored. Not working felt like I was just getting ready to die.” Recently, Gordon was contacted by a former colleague and hired to work four days a week at a company that provides cloud-based outsourcing for documents, on a salary lower than her previous job. She could not be happier. “I feel normal, and healthier,” she says.

A growing industry of “transition” coaches are cheerleading for later-life career makeovers: no longer retirement but “refirement”. Extended life expectancy challenges the traditional career arc. There was a brief debate on longer careers last year, when the Mexican telecoms billionaire Carlos Slim suggested working lives could continue to 75 by putting employees on a three-day week. The idea was endorsed by Virgin founder Richard Branson, who wrote in a blog post that the way we work will be in flux “as the way we live our lives changes”.

There has been a surge in older workers setting up businesses and entering self-employment.

However, a road builder is unlikely to match a desk-bound writer in occupational longevity. Diana Athill, the editor and writer, told me she carried on editing until 75 as she needed the money, then got down to “writing for the fun of it”. Esther McVey, the former Conservative employment minister, is reported as saying that the fact that Mick Jagger can still play sellout tours should inspire older people to reboot their careers. Clearly McVey has never had a life of physical labour.

Matt Flynn, the director of the centre for research into the older workforce at Newcastle University Business School, believes the traditional career path needs to be overhauled: “The idea that you can do all your education at the start of your career is no longer true, if it ever was.” Chris Ball, specialist adviser on the ageing workforce for the Shaw Trust, a not-for-profit employment group, agrees. He is frustrated that well-intended champions of older workers emphasise their role as the voice of experience and risk feeding stereotypes: “The blunt truth is that employers value the hard skills more than the soft skills. We need to invest in maintaining hard skills, particularly IT, through the life of a career.”

David Sinclair, the director of the International Longevity Centre-UK, notes: “We need to be careful about saying older workers are reliable. It feeds an image that they are safe and steady, when in fact people innovate across their entire lives.”

Plan, plan, plan

Mike Saunders believes the key for older workers is not to be fixated on status and traditional jobs but to experiment and hustle. Rangy and inquisitive, the only clues to the 77-year-old’s age are the record player and Winston Churchill statuettes dotted around his east London flat. As a boy, Saunders sold nylons at the local market in his Welsh home town, before crossing social terrain via grammar school to join the professional classes, first in the civil service and then for IBM, the tech company.

In 2003, he took over Wrinklies Direct, the small recruitment company he had helped run since 2000. It found jobs for those in their fifties, sixties and seventies (although discrimination laws did not permit him to advertise it like that). The candidates were, he says, “very much a mix . . . you name a skill and I could find someone in my database”. He says there were broadly three types of wannabe worker: experienced senior people who had been made redundant and wanted a new role; retirees who missed work; and people who struggled to find work because they had limited skills or were minority groups. It was a small business but he believes he placed one person a week. When the financial crisis unleashed damage on the economy, few companies were hiring so he scaled back. Now he will help someone find a job or a recruit if asked but no longer solicits clients.

Older workers must be entrepreneurial, he says. “They should pick up a company’s annual report, identify where that business can improve, then knock on the door and say, ‘I’ve always admired your company, you have challenges in this area and I know I can help you because this is what I’ve done in other companies.’”

Lynda Gratton, professor of management at the London Business School, believes people have their head in the sand when it comes to career planning for their sixties and seventies. She is fearful for the future. “Most people are in denial,” she says. “They don’t think it’s going to happen to them, that somehow they’re not going to live to 100 and their pensions are going to carry on.” Her research, with Andrew Scott, professor of economics at LBS, finds that those on good salaries who live to 100 can only retire at 80 if they save 14 per cent of their earnings throughout their working life and can live on 50 per cent of their income.

Diana Athill, editor and writer, finally ‘got down to writing for the fun of it’ at 75, having spent years editing to earn money

Last year, Gratton surveyed her MBA students, asking them to envisage their working lives after 60. All, without exception, anticipated a “portfolio” career. This is the kind described by the management commentator Charles Handy in his 1994 book, The Empty Raincoat, as “a collection of different bits and pieces of work for different clients”.

Gratton is incredulous at her students’ assumptions: “You can’t just suddenly conjure that up.” Two things have come out of her research on working into later life: the first is that people have to be prepared to experiment. The second, they have to plan. “There’s no way in the world you can conjure up, at the age of 60, a portfolio, unless you’ve actually built one up,” she says. “People are going to have to invent themselves,” she adds, because nobody around them will do it for them.

The inventor par excellence of career models is the aforementioned Charles Handy. The son of an Irish Protestant clergyman, he worked his way up the corporate ladder at Shell, the oil company, before becoming intrigued by organisational behaviour. One Monday morning, I meet him at his home in affluent Putney, southwest London.

The Second Curve, his latest book, applies to institutions and companies but also individuals planning for an extended working life. According to Handy, now 82, preparation is key to elongated careers: people need to change and start the second curve of their career before the first curve peaks (the timing of which varies from career to career). “You must have some energy and resources to retrain. And that’s very difficult, because you’re reaching the peak of the first curve when you’re quite successful. You want to go on. If [you are too] late you’re already downhill and it’s very difficult to get up again. If you want a successful third age, you need a third act. You need to plan for it.”

He says his motivation has changed over the years. “You cease to be so competitive. All you can be is you. Quite often that’s very satisfying.”

The U-shaped curve in happiness is well-documented. Economists have found that there is an average mid-life dip in happiness — or subjective wellbeing — in people’s early forties. Dr Hannes Schwandt of Princeton University, last year published research on “unmet expectations”. It found that while the young are optimistic, those in their forties and fifties can feel remorse before they make their peace in old age. He posits that older people have accepted their lot and adapted their expectations. Studies also show that long-term decision-making improves with age, as does coping with uncertainty.

‘Much happier’

A back-up plan is ultimately what saved Tim Hulse when he was pushed out of his IT sales job. Before redundancy, he had started to study for a masters in architecture from the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales, to while away the time in hotel rooms when travelling overseas for work. The severance package gave him the funds to start a sustainable construction company, EcoVert Solutions. “I wanted to do something meaningful. It felt like everything I had been doing was pointless.” Now in its third year, it has a turnover of just under £300,000 and employs seven people.

There is no doubt in his mind that he will continue working for some time. “I’d love to see myself in my eighties sticking my nose into things. Or I could sell the company and consult.” Part of the driver of setting up a business was so that he could continue to work for decades. “The longer you work, the longer you maintain your faculties.”

He pauses. “I’m grateful for the shift. I’m much happier now. It’s nice to create something. It’s made me much more aware of what really matters.”

Emma Jacobs is a features writer for the FT and author of the Working Lives column

Portraits by Rick Pushinsky and Jason Andrew

Photographs: Getty; AP

Comments