Hanergy: The 10-minute trade

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For the past two years, 3.50pm in Hong Kong has been a golden moment in the soaring fortunes of Hanergy Thin Film Power Group, the $35.5bn solar company that has transformed its owner into China’s richest man.

A Financial Times analysis of two years of trading data of Hanergy Thin Film stock — more than 800,000 individual trades on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange — shows that shares consistently surged late in the day, about 10 minutes before the exchange’s close, from the start of 2013 until February this year.

Reporting teamThis story was also reported by: Martin Stabe, Callum Locke, John Burn-Murdoch and Robin Kwong

The late-day outperformance of HTF, which has emerged as the world’s biggest solar company by value, is a stark reminder that in stocks trading, timing is everything.

It means that an investor who held HTF shares from the start of trading at 9am to 3.30pm would have lost money — despite the company’s share price rising by 1,168 per cent between January 2013 and February 9 2015.

A trader who bought HK$1,000 ($129) worth of HTF at 9am on every day of trading since January 2 2013 and sold those shares at 3.30pm each day, would have seen their money shrink to HK$635 by February 2015. But if they held on for just under half an hour more each time, the HK$1,000 would have turned into HK$8,430. This calculation does not include overnight gains.

Analysing the surge

HTF is the listed arm of Hanergy Group, a private Chinese company that has taken a big bet on thin film solar. In less than two years, HTF has surged making it worth more than Twitter or Tesla, the electric carmaker, and its founder Li Hejun, who owns 73 per cent of its shares, China’s richest billionaire.

The FT examined 140m individual trades from top listed companies in Hong Kong to explore the soaring share price of what until last year was a little known small-cap solar company.

Nothing within the data explains why the HTF surge happens. But analysts, who examined the FT findings, as well as the raw data, laid out three possible scenarios: market manipulation by an unknown trader, an algorithmic trading program is at play, or it occurs randomly.

Rajesh Aggarwal, professor of finance at Northeastern University in Boston and an expert on stock market manipulation cases, also reviewed the FT findings and raised the spectre of manipulation: “This is consistent with the stock price having been systematically manipulated over the past couple of years. This pattern of large price increases during the last 10 minutes of trade is extremely unlikely to have occurred randomly.”

Hanergy has publicly addressed the steep rise in its share price over the past few months. The rise has confused analysts following the company and the solar sector itself. HTF previously attributed some of its gains to interest from mainland Chinese buyers — who are able to invest through a new Hong Kong-Shanghai Stock Connect programme. HTF is one of the most high-profile companies to benefit from Stock Connect.

The soaring valuation means HTF is now worth more than all Chinese solar companies combined, and more than five times the value of its next largest US competitor, First Solar.

In a statement to the Hong Kong bourse this month, Hanergy Group said it was not responsible for the swift rise in the share price.

“Our group, as the shareholder of Hanergy Thin Film, has not committed any so-called ‘propping up’ or taken any action to push up its share price,” the company said.

Too big to ignore

For this article, Hanergy said: “We are not aware of any reasons for these prices and volume movements. We have not received any queries from any party, including the Hong Kong financial regulators, raising this question to the company. We are not able to comment on your alleged finding because we are not supplied with the materials in your possession.”

The Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission, which regulates the stock market, declined to comment on the findings of the FT investigation.

HTF’s rapid rise to become one of the largest companies on the Hong Kong stock exchange has, in the words of one analyst, made it “too big to ignore”.

The FT earlier this year published articles about Hanergy and its business model, noting the listed company’s large reliance on sales to its mainland parent group and the low output at mainland solar panel factories. Hanergy Group has also accessed high interest shadow banking loans in China.

The company has emphasised that it recorded a net profit of more than HK$2bn for 2013 and has built a reputation as a leader in the solar energy industry.

Mr Li has said that thinner, lighter technology will make Hanergy Group, with factories across China and overseas acquisitions, an industry leader.

The FT analysis of raw data from the Hong Kong stock exchange — second-by-second trades every day for two years — reveals a remarkable, consistent pattern of returns benefiting HTF shareholders. The company’s shares rose in the last 10 minutes of trading in 23 of the 25 months analysed.

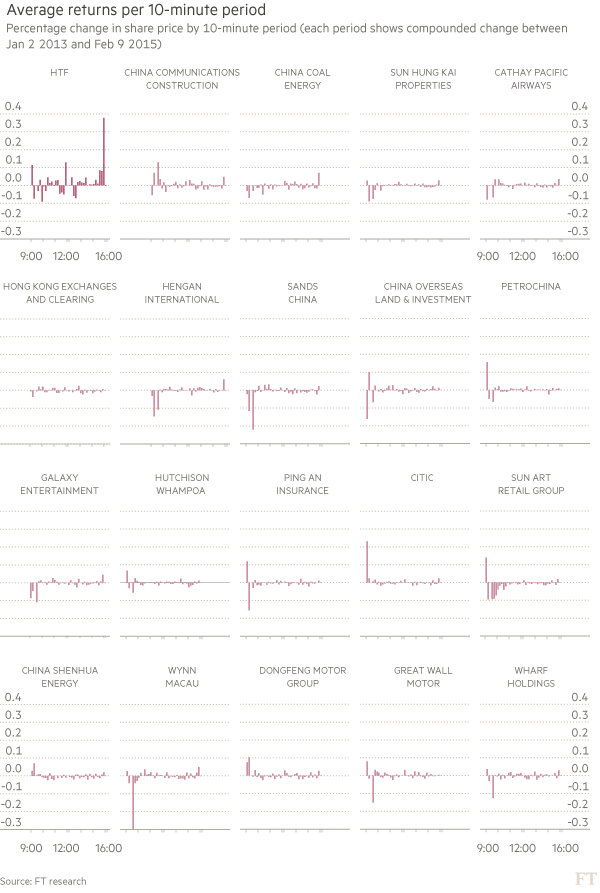

The same analysis was conducted on a randomly selected basket of 20 other Hong Kong listed companies; a few stocks had a more active late-day performance than others. But HTF was a significant outlier, as the charts below show. No other company came close to its end of day gains.

This calculation does not include the change between the close and the next day’s open.

Heavy trading at the end of the day is not unusual, but academic experts on stock market trading who examined the FT’s analysis say the pattern of large gains during the last 10 minutes of trading — with such regularity — is unusual. As Hanergy founder Mr Li holds 73 per cent of the HTF’s shares, this means that the amount available to trade freely on the market, the so-called free float, is highly constricted.

Eric Budish, associate professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School and an expert on financial markets, says it was highly unlikely that the late day price gains had occurred by random chance. He examined the raw data from the FT.

“Having looked at the data I can say that it’s certainly an unusual pattern, extremely unlikely to occur by chance,” he says. Mr Budish pointed to the persistence of the pattern over time. The fact that the pattern did not depend on just a few pieces of outlying data was, he says, a reason to believe it was not due to random movements.

At the end of the day

Carole Comerton-Forde, professor of finance at the University of Melbourne, who has written academic studies on the determinants of stock price manipulation, is familiar with the Hong Kong exchange. She considered the FT findings and the pattern of trades unusual, pointing out that end-of-day trading — for any exchange — is an important reference point for regulators.

“The official close is generally the most important official reference price for the market. Closing prices are typically used, for example, to set mutual fund net asset values, to settle derivatives contracts, for pricing equity offerings or for lending covenants from banks that have taken stock as collateral for loans.

“Therefore people have strong motivation to seek to influence or manipulate these prices because it will influence an outcome outside the market,” she says. “If there is a company where there is a limited free float this will mean it is thinly traded, and there is plenty of empirical evidence that suggests these stocks are more susceptible to manipulation.”

Mr Aggarwal also highlights the vulnerability of companies with a small free float to be manipulated by placing large but unfilled buy orders at the end of each trading day to artificially inflate the price of a particular stock.

Methodology: How the FT looked at the trading data

To investigate Hanergy Thin Film Power Group, the FT examined trade-by-trade data from the stock exchange over a two-year period beginning January 2 2013 to the end of February 9 2015.

The FT split this data into 10-minute periods and tracked the price at the beginning and end of each 10-minute segment in which the stock was traded. The entire data set for the stock exchange had 140m data points.

The HTF data are compiled from day-to-day trades, accounting for more than 800,000 data points.

Returns were calculated in two different ways: first, by finding the change in price between the first trade and last trade during each 10 minutes of the trading day; second, by finding the change in price between the first trade in one period and the first trade during the next 10 minutes of trading, as well as the change between the opening price and the previous day’s trading.

From this data, the average and compound return for every 10 minutes of trading over the lifetime of the stock was calculated. The pattern was examined month-by-month and day-by-day as well.

The FT used the statistical programming language R as well as SQL in its analysis.

Comments