The invasion of corporate news

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A population of 100,000 is no longer a guarantee that a city like Richmond, California can sustain a thriving daily paper. Readers have drifted from the tactile pleasures of print to the digital gratification of their smartphone screens, and advertising revenues have drifted with them. Titles that once served up debates from City Hall, news of school teams’ triumphs and classified ads for outgrown bikes have stopped the presses for good.

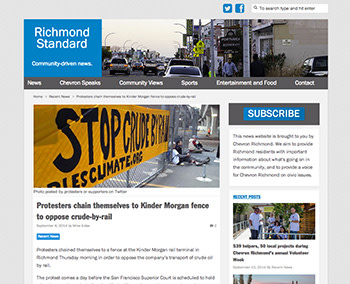

Last January, however, a site called the Richmond Standard launched, promising “a community-driven daily news source dedicated to shining a light on the positive things that are going on in the community”, and giving everyone from athletes to entrepreneurs the recognition they deserve. Since then, it has recorded the “quick-thinking teen” commended by California’s governor for saving a woman from overdosing; the “incredible strength” of the 5ft 6in high-school freshman who can bench-press “a whopping 295lbs”; and councilman Tom Butt’s warning about the costs of vacating a blighted public housing project.

The Richmond Standard is one of the more polished sites to emerge in the age of hyper-local digital news brands such as Patch and DNAinfo.com. That may be because it is run and funded by Chevron, the $240bn oil group which owns the Richmond refinery that in August 2012 caught fire, spewing plumes of black smoke over the city and sending more than 15,000 residents to hospital for medical help.

Its editor, a former San Francisco Examiner reporter called Mike Aldax, works for a public relations firm called Singer Associates, which offers clients advice on “issues management”. At a time when Chevron is planning a billion-dollar upgrade that environmentalists oppose, pitching itself as a friendly voice in the community must look like an appealing way to manage such issues.

In February, for example, an article reassured readers: “The clouds that could be seen above Chevron Richmond refinery Wednesday morning were actually harmless steam clouds.” Another highlighted refinery workers’ volunteer work at an animal adoption centre. In early September, Aldax covered a protest against Kinder Morgan, a rival energy company, over its shipments of “the highly volatile Bakken crude from North Dakota”, reminding readers of the deadly July 2013 derailment of a train carrying Bakken oil in Quebec.

The site – which is upfront about wanting “to provide a voice for Chevron Richmond on civic issues” – includes a section called Chevron Speaks where the company has challenged “incorrect and misleading information” in rival local publications by spelling out its argument that its refinery upgrade will reduce pollution and create jobs. When the Richmond Standard questioned the mayor’s ties to a PR firm “suspected of hiring phony protesters to demonstrate outside the Chevron shareholders meeting”, however, the article was tagged as news, not spin. Those ties “raise new questions about how far she is willing to go to battle Chevron, Richmond’s largest taxpayer,” Aldax wrote.

Ken Doctor, a news industry analyst who has studied the “muddying of the waters” between news and marketing, says of Chevron’s Richmond site: “There are not a lot of things that amaze me but that takes chutzpah to do that.” Chevron’s effort to make news on its own terms is, however, far from unusual.

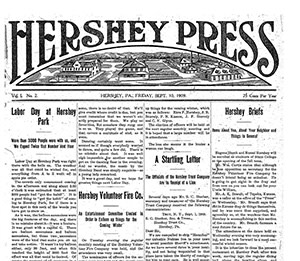

Richmond is not the first company town to have a company newspaper. In 1909, the Hershey Press launched in Hershey, Pennsylvania, featuring advertising from the chocolate maker and articles about its factory (“the finest manufacturing room in the United States”). But its first editorial declared that, in politics, “we shall boost the honest candidates for all that’s in us, and we shall then leave it up to you to do the deciding.”

Few of us live in company towns such as Hershey or Richmond but more of us than ever before are exposed to what its proponents call “brand journalism” – a new form of reporting that just happens to be produced by companies. Not much of it is produced with the aim of leaving it up to us to do the deciding.

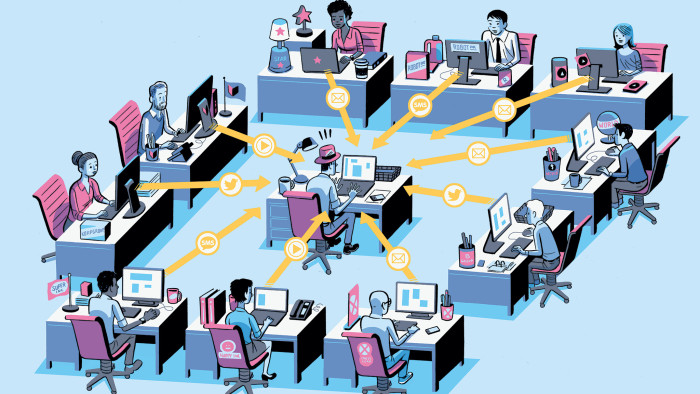

Social media and digital publishing tools are allowing this strain of corporate news to reach vast audiences, with profound implications for the way businesses communicate with the public and for the media outlets they are learning to sidestep.

…

For 20 years, as a reporter and editor in London and New York, most of my time has been spent doing the things non-journalists assume journalists do all day: developing sources, chasing leads, delving into secret files and polishing paragraphs. But I have also devoted countless hours to dealing with PR people. This has involved furious phone calls to protest at my underplaying a client’s view of the world, surreptitious forwarding of material helpful to the case being pitched, and friendly invitations to bend my ear over lunch or drinks. (Only twice has a PR person attempted to play footsie with me under the lunch table – I made my excuses and left.) Then there are the emailed pitches, trying to persuade me to spend time and reporting resources on stories of questionable value to the FT’s readers.

My inbox is clogged with the “barking news” about New York’s first doggie-treat truck, the invitation to meet the inventor of the multimedia coat hanger, the press release on the “trail-blazing” motorway service station and the survey on “slowcial networking” (otherwise known as sending greetings cards). There is the gobbledegook about “new paradigms”, “providers of proactive solution management systems” and “taking consumers down the marketing funnel”, and there is endless “circling back” from over-friendly strangers (“Hey buddy!” began one recent email) wondering whether their pitch “could be a nice fit for “Financial Times, New York Bureau” – a target picked blindly from the directory.

With the president-felling image of Woodward and Bernstein still hanging over the profession, and a geekily hip narrative of data-driven analysis pointing to a new future, few journalists like to acknowledge the role PRs play in their stories. Many are well-informed, professional, clever, helpful and fun. Some are former colleagues. Some become friends. But for most journalists, it is an involvement we put up with warily. PRs are spinners of favourable stories, glossers-over of unfavourable facts and gatekeepers standing between us and the people we want to get to.

But as journalists bemoan such PR obstacles, they rarely admit an important fact: the PRs are winning. Employment in US newsrooms has fallen by a third since 2006, according to the American Society of News Editors, but PR is growing. Global PR revenues increased 11 per cent last year to almost $12.5bn, according to an industry study entitled The Holmes Report. For every working journalist in America, there are now 4.6 PR people, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, up from 3.2 a decade ago. And those journalists earn on average 65 per cent of what their PR peers are paid.

As journalism schools pump out new generations of would-be Woodwards and Bernsteins, many of those not finding newsroom jobs have turned instead to the business of how to present the news in the most flattering light. They have been joined by laid-off reporters, editors, producers and presenters, with the skills to tell the stories brands want to be told about themselves. “[PR] agencies are now employing many more former journalists,” says Steve Barrett, editor of PR Week. “There are lots of refugees out there, really top-quality journalists who have gone into PR in a very specific way.”

Their efforts seem to be working. Cardiff University researchers estimated in 2006 that 41 per cent of UK press articles were driven by PR, a phenomenon known as “churnalism”. But PRs are now playing the news industry at its own game. They are discovering how to work around journalists, getting their own slickly produced stories, videos and graphics straight to their target audiences – often with the help of the very news organisations they are subverting.

…

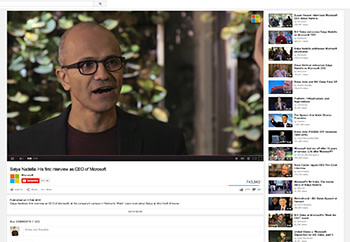

In the days before Satya Nadella was named Microsoft’s CEO in February, leaks to selected tech bloggers changed the discussion around the succession from disappointment at the prospect of an in-house replacement to a sense that it was only natural for Microsoft to elevate a veteran who had been at Bill Gates’ side for 22 years. When the announcement came, it sweetly told us that this was as long as he had been with his wife.

But with the traditional press release came an “asset pack” that Microsoft PRs shot out to century-old newsrooms and influential one-man blogs alike. It contained high-definition images of the new CEO looking relaxed but in charge, wearing a hoodie or purposefully clenching one fist as he addressed staff. And it included a biography describing him as a poetry-loving cricketer who “brings a relentless drive for innovation” to the job – good fodder for the “10 Things You Didn’t Know About Satya Nadella” listicles that followed.

Then came the videos: testimonials from Gates and outgoing CEO Steve Ballmer about what an ideal successor he was, and an unchallenging interview by an in-house blogger, conducted as they strolled casually around a people-free section of Microsoft’s headquarters. “How did you feel when you were offered the role?” asked the smiling employee. “Honoured, humbled, excited,” the newly minted boss replied. Nadella’s first interview as CEO ended with the blogger posing the softball question: “Why do you feel Microsoft is going to be successful?”

It was a masterclass in PR spoonfeeding and news organisations simply had to drag and drop. With no press conference or one-on-one interview in which to ask tougher questions about the challenges Microsoft faced, and no chance to send news photographers or videographers of their own, that’s what they did. The FT was among those that embedded one of Microsoft’s videos in its reporting that week (noting that it had been produced by the company), linked to and analysed Nadella’s blog and used the company-issued photographs.

The “asset pack” contained no mention of the thousands of planned job cuts that followed a few months later.

Burberry introduced its new CEO, Christopher Bailey, with a similarly glossy video calling him “one of this generation’s greatest visionaries”. (He, like Nadella, was “incredibly humbled” by his elevation.) And when Bill Ford announced the CEO succession at the eponymous car company from Alan Mulally to Mark Fields in May, Ford offered the media three videos of the event with Pyongyang-worthy headlines such as “Mark Fields discusses the power of One Ford and great products”.

The pressures on news outlets to become multimedia, interactive, 24-hour engagement machines mean editors have become increasingly receptive to what PRs are pitching. A hungry media swallows it up. And with institutions more wary than ever of unpredictable journalists, executives are now more inclined to share their thoughts in smoothly styled social media postings than by inviting in a reporter.

Sir Richard Branson, for example, says he used to talk first to newspapers to get messages out about his business or his philanthropy. But now Virgin’s one-man brand has more than 1.5 million Facebook likes, 4.4 million Twitter followers and an unrivalled 6.3 million people following him on LinkedIn. “Now we’ve got a way of reaching people who read what we say and we don’t have to rely on the Daily Mail,” he observes.

CEOs are finding that their unfiltered social media content is often picked up by the traditional media it has circumvented, PR Week’s Barrett notes. So when General Motors’ new leader, Mary Barra, was going before Congress to explain how the carmaker had ignored warnings about the role of a faulty ignition switch in fatal car crashes, she recorded an emotive YouTube video explaining how “as a member of the GM family and as a mom with a family of my own, this really hits home for me”. The New York Times was among those that embedded her sombre-toned performance in its online story.

Few have succeeded in making the news as well as Apple. This month, as it unveiled the iPhone 6 and the Apple Watch in Cupertino, California, thousands of journalists live-blogged every detail of the carefully scripted event. But the company also ran its own live blog, a feed of perfectly lit images of the devices, shareable quotes from executives, retweeted endorsements from celebrities including Diddy and Katy Perry and a gushing running commentary (“So far, so amazing”). The front rows of the hall were reserved for Apple employees and guests, who provided periodic ovations for the media cameras behind them.

It is an uncomfortable fact for journalists that a business famous for its controlling approach to the media and its ambition to dictate its own story has become one of the world’s most successful – and usually gets glowing coverage. Apple is not alone: from the White House to Wall Street, journalists protest that they are getting less meaningful access to those in power than ever.

…

“People these days don’t care as much about where the story comes from as long as it tells them something,” says Tomas Kellner, a Columbia Journalism School-trained former Forbes journalist who now edits GE Reports.

General Electric’s online news site has evolved from a list of press releases to a virtual magazine using animated gifs, professional photography, videos and infographics (“all the different points of entry we used at Forbes”, Kellner notes) which features tales of innovation, science and technology from around the giant industrial group. Many are engaging and informative, and some – such as a feature on a Japanese indoor lettuce farm powered by 17,500 GE LED lights – get as many as 500,000 readers.

Kellner, who does most of the reporting, sees himself as following in the footsteps of Kurt Vonnegut, the Slaughterhouse-Five author who joined GE as a publicist in the 1940s. Vonnegut was one of its “early content gatherers”, roving around GE’s operations to find ideas for stories which he would then pitch to reporters, Kellner says.

“There have been corporate newsrooms for ever but they were putting out press releases to try and get you guys to cover it,” notes Richard Edelman, whose family firm is the world’s largest PR agency. “Now it’s self-publishing. That’s the big difference.” Every company is now realising that it can be a media company, he says.

Companies’ self-published content often makes it into blogs, newspapers and news bulletins even without much pitching. “We get picked up by tech blogs like Gizmodo and Engadget quite regularly,” Kellner notes: “They sort of validate what we are doing.” For GE’s global head of digital programming, however, such tech blogs are also competition. “Our content has to be as good as theirs, if not better,” Katrina Craigwell told eMarketer in June.

In some areas, marketers are looking to fill gaps left by a retreating press. GE Reports has launched local versions from Indonesia to Europe, says Kellner, because “in an era when newspapers are closing foreign bureaux and cutting their foreign coverage, we’re moving the other way and trying by virtue of being a global company to tell the global story.” Indeed, Simon Sproule, a former communications director for Renault-Nissan who is now chief spokesman for carmaker Tesla, told PR Week that Nissan opened a media centre in Yokohama in part because so many international news organisations had closed their Japanese bureaux that “we felt our stories weren’t being told.” Its state of the art newsroom would put many television studios to shame, Barrett says.

GE and Nissan are not isolated examples. Sites such as Wells Fargo Stories, Target’s A Bullseye View, iQ by Intel and Shell’s “secret circuits” drivers’ guides to different cities are all well-produced examples of the growing genre. Much of the content looks as though it could have come from a magazine. On the Coca-Cola Journey site, such tweetable articles as “5 interview tips for millennials” sit alongside an on-brand feature from the doyenne of domesticity Martha Stewart on the Coke Float (a glass of cola topped off with vanilla ice cream). Indeed, much of it is produced by former journalists, says Ashley Brown, who built Coca-Cola’s content marketing programme before joining Spredfast, a self-described social marketing company. Brands need storytellers, and journalists represent the greatest pool of storytelling talent out there, he says. At Coca-Cola, “we wanted people who know how to package up a story with tension and emotion, and more importantly know how to do it quickly and efficiently.”

If they can produce content that is sufficiently emotionally engaging and useful, he notes, fans will share it on social media. “We advise customers that the world needs more great content,” Brown says. But broadcasters and magazines no longer have a lock on distributing compelling stories: individual consumers are just as likely to do the job for brands.

The strategy behind content marketing is similar to Michelin’s thinking when it produced its first guide for drivers in 1900 or machinery maker John Deere’s 1895 magazine for farmers, The Furrow, but the scale is dramatically different. Coke’s digital-era take on “brand journalism” or “content marketing” got more than 13 million visitors last year.

Some such content is less transparent about its origin and reads more like a lobbying campaign. A slick site called Advanced Energy for Life warns of the threat of “energy poverty”, applauds Australia for repealing its carbon tax and talks up coal’s importance in meeting the world’s energy needs in multimedia items including a video of America’s Got Talent star Jimmy Rose singing “Coal Keeps The Lights On”. Only in the small print is it mentioned that the site is sponsored by Peabody Coal, the world’s largest private-sector coal company.

…

Marketers talk about “paid media” (advertising they have to buy), “earned media” (from press coverage to word-of-mouth buzz) and a growing category called “owned media” (their websites, blogs and social media feeds). The attraction of “owned media”, by definition, is that brands neither have to pay a media outlet for it nor earn it by convincing a reporter that the story is worth covering. That is a problem for the news industry’s ad sales teams and newsrooms alike.

The pressures on news business models have forced the industry to innovate, and in newer newsrooms such as Buzzfeed, Mashable, Quartz and Vice, “native advertising” has become a favourite buzzword. There is little consensus about the definition but it typically means paid ads that look much like the articles and videos they sit alongside.

This digital spin on traditional advertorials has been dubbed “one of the great euphemisms of our time” by ESPN president John Skipper and “repurposed bovine waste” by comedian John Oliver, yet native advertising has won over some of the most established brands in news, with The New York Times and Time among those embracing the trend.

As well as featuring advertisers’ “paid posts” on its homepage, The New York Times is placing its own native ads: on Mashable, you can find “11 Inspiring Videos That Will Restore Your Faith in Humanity” under the label “presented by The New York Times”. It has been shared more than 3,000 times.

Some publishers have gone further, enthusiastically lending their editorial expertise to help brands improve their content. The Wall Street Journal’s newsroom is not involved in sponsored content but its commercial team tells advertisers it can “deploy sophisticated storytelling techniques in order to help brands create content-driven connections with audiences”. For some reporters and editors, this is tantamount to media being complicit in its own displacement. Yet few readers have protested.

For PR Week’s Barrett, this point is at the heart of the debate over whether “brand journalism” counts as journalism. “Is it news? At the end of the day, the consumer decides,” he says.

As the lines blur between news and advertising, however, analysts such as Ken Doctor fear that not all consumers will be able to distinguish a news organisation’s story about BP from BP’s own stories about itself. “The Facebook stream and the Twitter feed have brought the numbing sameness to all content on the internet,” he says. With some critics already doubtful that journalists are capable of reporting news impartially, Doctor argues: “The news industry has not done a good job of saying what makes journalism different.”

For Edelman, head of the world’s largest PR firm, brands’ desire to place their content alongside journalists’ output is a sign that they understand that the public trusts the media’s stories more than those told by business. Edelman’s annual Trust Barometer survey found this year that 61 per cent of those polled across 25 countries trust traditional media, compared with 43 per cent who trust “owned media”.

Spredfast’s Brown believes the two industries can co-exist. “There’s always going to be a need for journalists who cover the world in an objective way,” he says. Besides, he notes, the surest way for branded content to get social media buzz is for it to be covered and shared by traditional news outlets.

As trust in business has fallen, the appeal of telling stories that humanise companies has grown. The history of advertorials shows that brands have long wanted their advertisements to look like news, but as the subjects of news increasingly want to decide what counts as news, and as they get ever more skilled at doing so, they are posing a challenge to journalism’s traditional storytellers.

Appropriately, the challenge may have been summed up best by the words of their new digital competitor at GE: “Our content has to be as good as theirs, if not better.”

Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson is the FT’s US news editor

Photographs: Courtesy of Hershey community archives; YouTube

Illustration by Lucas Varela

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Stormin’ Norman shaped trend for self-serving news / From Mr John R MacArthur

Comments