China’s environmental activists

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On a sunny summer’s day in the city of Kunming, a leafy town in southern China famous for its mild climate, Mayor Li Wenrong found himself in a bind. Hundreds of angry protesters were marching outside the city government building, the second such demonstration in as many weeks. After four hours of chanting – and as the police presence continued to build – the mayor decided to go out and address the crowd.

Their demands were clear. They wanted the mayor to halt the construction of a giant new petrochemical plant that was under way in a neighbouring county. In particular, the protesters were concerned about the pollution the plant would release as a byproduct of producing paraxylene, a chemical used in plastics.

As Mayor Li tried to address the crowd, he found the crowd addressing him too. Why hadn’t the public been consulted before construction began, people wanted to know. Why weren’t the local papers allowed to write critically about the plant? Why wasn’t he holding a public referendum and letting everyone vote on the matter? These were some of the questions that flew at the mayor, according to the accounts of those present.

Standing stony-faced amid a thick security detail, Mayor Li experienced, in physical form, the dilemma that is facing the Chinese government as environmental protests grow. On the one hand, the country’s leadership has publicly committed to tackling the chronic pollution that has accompanied the economic growth of the past three decades – the same goal environmentalists share. At the same time, the forces unleashed by China’s environmental movement are often deeply unsettling to the country’s authoritarian officials.

The protests in Kunming this summer, which resembled dozens of similar cases across the country, might never have happened if it weren’t for China’s new social-media platforms. Demonstrators in Kunming found out about the plant and decided to take action by communicating on Weibo, a Twitter-like “microblogging” service, and through WeChat, an instant messaging service for smartphones. Although construction of the plant is still going ahead, Mayor Li has made at least one change to his governing style: he now has a Weibo account.

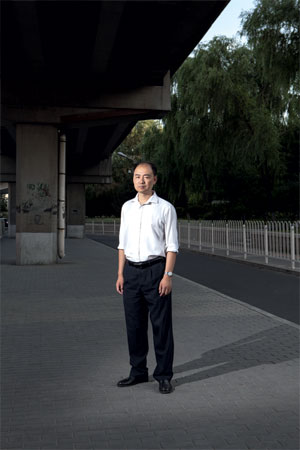

Environmental activists often point to the emergence of social media such as Weibo as a turning point for their cause. “Chinese people were like shattered glass before we had Weibo. There was no way to unite,” says Deng Fei, an activist who has nearly four million Weibo followers and has used the platform to launch campaigns on everything from philanthropy to conservation.

Even the simplest Weibo message can become a movement. Earlier this year, Deng asked his followers to post photographs of polluted rivers and lakes in their hometowns. The outpouring of images prompted a series of press articles and shamed several local governments into cleaning up their waterways. Today, Deng, a journalist at Phoenix Weekly, a news magazine based in Hong Kong, spends the bulk of his time running the collection of environmental and social organisations that he has founded – and funded – largely through online support. His most recent project is the China Water Safety Foundation, launched last month.

“No matter where you are in China, within four seconds you can post something to the whole world,” he says, thumbing his iPhone as we talk. “I like to say that Weibo is God’s greatest gift to the Chinese people. It has given us more power and more rights, and allows us to come together quickly.”

China’s citizens have come together rather quickly over pollution, because the scale of the problem is immense. In terms of air pollution, seven of the world’s 10 most polluted cities are in China, and the smog contributes to more than a million premature deaths each year. The water is little better. According to official statistics, a third of the water in China’s major rivers is too toxic for human contact. Wide swaths of soil are contaminated with heavy metals, but the full extent is unknown because the government has labelled soil-pollution information a state secret. China is also the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide.

The sources of much of this pollution are the factories, industrial plants and power stations that have been the engine room of the country’s economic growth. As China has catapulted through the ranks of developing countries over the past 30 years, emerging as the world’s second-largest economy in 2011, massive pollution has been a byproduct, just as it was for the US and Britain in earlier eras.

Increasingly, China’s leaders say the trade-off is no longer worth it. As Premier Li Keqiang said earlier this year: “It’s no good to be poor in a beautiful environment, but nor is it any good to be well-off and left with the consequences of environmental degradation.” Officials have warned that China’s pollution problem is a source of social instability, and a bottleneck that will limit economic growth. Beijing announced in July that it was drafting a new Rmb3.7tn (£380bn) plan to tackle air and water pollution – in addition to the billions that are already being spent each year.

It’s only recently that official pollution-control efforts have gained the added dimension of being a large-scale public movement, thanks to a combination of “nimbyism”, growing awareness and social media. China’s heavy industry is already feeling the effects. After high-profile protests like the one in Kunming, the government’s concern over potential public dismay has prompted officials to shelve a series of industrial projects across the country. In July, a $6bn uranium-processing project in Guangdong province was cancelled the day after a protest against the plan. In August, a coal-burning power plant in Shenzhen met a similar end.

Some environmentalists, such as Ma Jun, the founder of a prominent pollution watchdog group in Beijing, credit the capital city’s toxic smog as an important “wake-up call” that changed public attitudes. For several years, the only public source of real-time information about Beijing’s air quality was a monitoring station on top of the US embassy, which sent readings out every hour on Weibo and Twitter. In 2011, Beijingers started demanding that the city government publish its hourly pollution data too, instead of keeping it secret. When the city government complied a year later, it was a landmark victory. “The disclosure led to some real snowball effects. People realised this is real pollution, it is not fog,” Ma says, referring to what used to be a commonly held belief. “Now everyone has to face the data and come out of their comfort zone.”

The rising per capita income of China’s city dwellers is another reason that more of them are clamouring for stronger environmental protection. “They find they have reached a ceiling. No matter how rich you are, you can’t get healthy air,” says Ma. “Now it is about everyday life, everyday discussions with your child, who probably can’t go out of doors.”

Ma has worked for years on increasing pollution transparency, because he trusts that once the data are available, public pressure will do the rest. Seven years ago he founded the Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs in Beijing, which compiles official pollution data and violation records. He smiles as he shows off his latest tool – a pollution database for publicly listed Chinese companies. “You just have to type in the ticker code,” he says, as a list of large Chinese companies, mostly state-owned, pops up on his screen. Having an impact on the state-owned companies can be difficult – often they are more powerful than the environmental bureaux supposedly monitoring them. Ma thinks appealing to their shareholders might be more effective.

…

More than 1,000km away from Ma’s Beijing office, on the edge of the Tengger desert in Inner Mongolia, dozens of small chemical plants stand idle and dark, facing the sand. The air has an acrid edge, but the entry in Ma’s pollution database shows that this place, the Tengger Industrial Park, has been shut down since March. The reason: the park had no wastewater treatment facilities. All these chemical plants had simply been dumping their effluent in the sand.

“No one lives in the sand dunes, so the companies think, ‘This is great – it’s the perfect place to discharge pollution,’” says a ruddy-cheeked Mongolian herder who grew up here and was born a few miles down the road. “Little did they think that Bayar would get in their way,” he says with a mischievous smile.

Bayar is a thirtysomething local who only made it part of the way through high school, but he has been a thorn in the side of the industrial park for the past two years. (Like most Mongolians, he goes by one name.) After working odd jobs in various parts of China, he returned to his home town two years ago and was shocked at what he saw. “This used to be perfectly good grassland, and then when I came back, you could barely breathe the air.”

He decided to do something about the discharge from the plants, which he believed was contaminating local groundwater. After the county government and local newspapers ignored his inquiries, he went online and reached out to environmentalists in Beijing. Eventually one responded. One thing led to another and, months later, China’s national TV station aired a short clip about pollution in the industrial park. The same day, all the chemical plants were ordered to close down.

“Suddenly I was very happy, and very worried,” Bayar recalls. “Worried about too many things.” His phone was tapped, his driveway was put under surveillance and the village head started dropping in on him every day. Nevertheless, driving by the rusting plants that look like they might have been abandoned, he seems pleased with the result.

The environmental movement doesn’t have obvious leaders: it’s a groundswell of people like Bayar. It also has its limitations, of course. A few months after the plants closed down, Bayar realised they were actually still running – at night. And plans for two new giant petrochemical facilities in the area were still forging ahead.

Another challenge is that few of these citizen activists have much scientific background, and on Weibo rumour is frequently passed off as fact, sometimes causing erroneous information to proliferate wildly. (Deng was himself recently forced into a climbdown after 25 companies in Shandong province were cleared of pumping polluted water underground.)

There is also wide debate about how long this new-found freedom to protest will last. “Every day we have to think, ‘How much space do we have?’ ‘Where are the red lines?’” says Ma, the pollution monitor. This month the government announced that people who spread “irresponsible rumours” online could be punished by up to three years in jail. Several high-profile microbloggers have been detained since the announcement was made – including one who played a leading role in the Kunming protests.

“You can’t control a sea in the same way you control a lake,” says journalist-activist Deng, referring to Weibo. “The government see it themselves now. They realise they can’t corner public opinion, only guide it.” But in environmental protest, public opinion often hits uncomfortably close to home. Local government in China is frequently deeply entwined with heavily polluting industry, whose tax revenues enable cities and towns to function. In many parts of the country, the very place where people want to shine a light is where their local leaders – like Mayor Li, listening to the protests growing louder outside – would rather not look.

——————————————-

Leslie Hook is an FT Beijing correspondent. Additional reporting by Wan Li in Beijing.

To comment, please email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments