The lost pages of ‘Longitude’ by Dava Sobel

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The tercentenary of the Longitude Prize, established in 1714, draws me happily back to Greenwich this year to commemorate the act of parliament that helped the world find its way. The prize of £20,000 [worth £2.8m today] encouraged John Harrison of Yorkshire to build a series of singular sea clocks for George II and George III. These timekeepers not only carried the day, they set explorers on a path to the moon.

I know that claim sounds exaggerated but, in fact, when the astronaut Neil Armstrong dined at 10 Downing Street upon his return to earth, he raised a glass to Harrison, “the one who started us on our journey”.

The 2014 tercentenary will be my third longitude tercentenary within three decades – a ter-tercentenary, if you will, or perhaps tri-tercentenary. The first occurred in 1993, when the 300th anniversary of Harrison’s birth occasioned the Longitude Symposium at Harvard University. I covered that three-day conference as a reporter for Harvard Magazine. New then to the lore of longitude, I marvelled as speakers unravelled Harrison’s unlikely tale of originality and determination – how a man of indifferent education arrived at a solution that eluded the likes of Galileo and Newton.

The organiser of the Harvard event, Will Andrewes, had looked after the clocks at the Royal Observatory before moving to the US as director of the specialised Time Museum near Chicago. In 1993, he was serving as curator of Harvard’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Harrison had been his hero since boyhood.

As a treat for the several hundred clock experts attending the symposium, Andrewes gathered a few 18th-century timepieces from the collection and opened their works to inspection. Jewellers’ loupes and small telescopes emerged from the pockets of excited enthusiasts, who contorted themselves to savour that unique opportunity.

Soon, Harrison became my hero, too. The assignment for Harvard Magazine morphed into a book project for a New York publisher, then found a home in the UK with 4th Estate, which issued and reissued Longitude in hardback, paperback, illustrated, boxed and film tie-in. Writing about finding position at sea helped me find my place as an author.

The second longitude tercentenary, in 2007, honoured the legions of sailors who drowned the night Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell made his disastrous landfall among the Isles of Scilly. A smaller group of celebrants gathered this time, on St Mary’s, for a new set of talks and a solemn ceremony at sea. A Royal Navy minesweeper carried us through light fog to the rocks that had dashed the admiral’s fleet. Lurking among the waves in the mist, the jagged stones called to mind the open jaws of a shark. No other setting I had ever seen so perfectly communicated a sense of hopelessness. We spread prayers and wreaths on the water, then returned to safe harbour on that otherwise beautiful island.

Andrewes, unfortunately, was not able to participate in the St Mary’s tribute. The previous year, however, I had stood beside him and his wife Cathy near the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey, watching the Duke of Edinburgh unveil a memorial plaque for John “Longitude” Harrison. Although the Abbey function did not classify as a tercentenary, it did coincide with the date, March 24, of Harrison’s birth in 1693 – and also the date of his death on March 24 1776.

Earlier on the morning of March 24 2006, before the Abbey opened its doors, we visited Harrison’s grave at St John’s Church, Hampstead. Although the sky was still dark when we arrived, we found that someone had preceded us in placing flowers around the stone. We thought we knew who that pre-dawn visitor must be – a certain clockmaker friend of Andrewes’ on an annual pilgrimage to the cemetery. Then again, any one of the local citizens, touched by Harrison’s struggle or inspired by his perseverance, could have strewn the bouquet.

I often wonder why it fell to me to tell Harrison’s story. Me, an American relating a piece of British history, a woman describing events peopled entirely by men (pace Queen Anne, during whose reign the prize was offered), a person with no special mechanical talent and only scant – mostly traumatic – experience of sailing.

My father bought his first boat, a rowboat, on an outing with my mother and older brothers at City Island, a small maritime centre near their home in the Bronx. By the time I was born, they had graduated to a motorboat. Somewhere out on the waters of Long Island Sound, in short spells away from his medical practice, my father developed a passion for sailing and learnt how to handle a sloop.

My mother reacted by enrolling in navigation courses at night school with the Power Squadron, where she became adept at reading nautical charts. She purchased a sextant. One evening in the early 1950s she drove me to a deserted beach where she could practise taking sights. Policemen stopped to question her intentions. It was the sort of pickle no one else’s mother got into. How I wish I could recall the details of the police interrogation.

Because my father took limited vacations, we sailed off when he could get free, and the weather be damned. Over the summers of my childhood, at least three Atlantic hurricanes caught us in their maws. I remember being tied to the deck in the cockpit. I remember hearing my mother murmur, “Somebody please throw me overboard.”

The morning after one of those ordeals, a small plane approached, circled, dropped down and buzzed close enough to our stern to read the name painted on it. A relative, fearing we’d perished in the storm, had sent the coast guard looking for us.

My mother was still alive when I wrote Longitude, and I wrote it for her. Beyond the dedication that mentions her name and her native Brooklyn neighbourhood, Canarsie, I kept her in mind as the book’s ideal audience – maybe, I feared, its only audience. When others asked about my current project, and I told them, “a brief account of how the problem of determining position at sea was solved”, most people just looked down, speechless and a little embarrassed. But my mother could hardly wait to read each chapter as it was finished. She read the finished book a few times over.

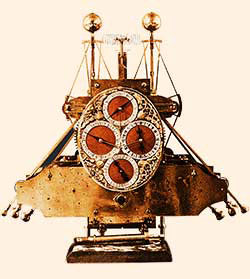

The long arc of Harrison’s achievement continues to win him new followers. Modern horologists are replicating his experiments in materials science and barometric pressure to prove the truth of his claims for accuracy. A few of his admirers have replicated his machines, crafting full-scale working copies of the sea clocks.

All of Harrison’s original timekeepers remain in good working order. All of them – from the wooden tower clock at Brocklesby Park to the glorious moving sculptures of gleaming brass at the National Maritime Museum – still keep good time. Their friction-free parts continue to rock and whir and mesmerise their viewers. The tercentenaries of their completion dates, looming on the horizon, promise cause for future celebrations.

——————————————-

The missing fragment

This episode was omitted from Longitude as the drama unfolds on land rather than sea

The Longitude Problem is usually associated with the sea – with the sad fates of square riggers that lost track of their position soon after losing sight of land. But the life and untimely death of French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, carried the longitude tragedy on to the continent of North America.

La Salle, who had come to Canada in 1667 as a bold youth of twenty three, started as a fur trader but soon distinguished himself as an explorer. In his quest for a land route to the Orient, he headed west from Montreal, befriending the natives as he went, and learning their languages. He conquered the inland waterways of the Great Lakes and the Ohio River. From a point on the Niagara River near Buffalo, La Salle launched the first sailing vessel to navigate across Lake Erie. Heading on, now paddling and now carrying their canoes, La Salle’s men travelled north along the length of Lake Huron and south down Lake Michigan to the Illinois River. This was a journey of several years’ duration, and that also resulted in the founding of four forts along the way – Niagara in 1679, Saint Joseph and Crevecoeur in 1680, and Saint Louis in 1682.

Then La Salle met the mighty Mississippi River, on what is now the eastern border of Missouri, and followed it to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. In a formal ceremony on 9 April 1682, La Salle claimed the whole valley surrounding his route for King Louis XIV of France. It was the biggest land-acquisition move since Columbus’s claim nearly two centuries earlier.

La Salle called his land Louisiana. (He also tried to rename the Mississippi River in honour of King Louis’s chief minister – the River Colbert – but that name didn’t stick.)

After his advance of more than a thousand miles through virgin territory, La Salle was forced to return to France in a web of political intrigue following the recall of his patron, to go back to Louisiana in earnest. The King gave La Salle carte blanche to penetrate Spanish territory bordering the Gulf of Mexico, and to exploit any silver mines he might find. Beyond this, the King also gave him money, ships and troops to carry out the mission with his blessing.

But no one could tell La Salle how to find the mouth of the Mississippi again, coming at it now from overseas instead of overland.

He set sail across the Atlantic in the summer of 1684, and entered the Gulf of Mexico that winter. As he did not know the longitude of the spot where he had staked his claim – or the ship’s longitude at any time on the voyage – he sailed clear past his Mississippi delta destination. About four hundred miles west of the scene of his triumph, La Salle landed on the Texas coast, at Matagorda Bay, early in 1685.

Although he had “wested” too far already by ship, he continued west on foot to a prairie, where he obeyed King Louis’s orders to build a fort. His men ate the plentiful buffalo and made friends with the Cenis Indians. More than a year passed, and still La Salle did not know where he was. It proved impossible for him to reconcile the crude maps of the region with his memories of the river, or even with the latitude readings he had taken himself by astrolabe upon his initial discovery.

In April of 1686 he ventured north, hoping to hit one of the huge bends in the meandering river. Several members of his search party deserted along the way to join the Indians. Others took sick, and one was eaten by an alligator. Only a few survivors straggled back with La Salle to Matagorda Bay in August.

At last, in January 1687, he picked a few of the King’s soldiers to accompany him on one final search for the place where he had buried a cross, a plaque, and a white banner five years before.

He led them north again, but after just two months the crew mutinied right there on dry land. The dawn of 18 March 1697 saw La Salle shot through the head by the men so weary of following him. Then they stripped his body and threw it to the wolves. He suffered a dishonourable death – far different from the regal burial he might have expected, and still at least two hundred miles from the seat of his Louisiana empire.

——————————————-

A special anniversary hardback edition of ‘Longitude’ by Dava Sobel is published by 4th Estate on February 27 (£12.99)

‘Ships, Clocks and Stars: the Quest for Longitude’ opens at the National Maritime Museum on July 11; rmg.co.uk.

To comment, please email magazineletters@ft.com

——————————————-

Letter in response to this article:

Tireless restorer of the Harrison clocks / From Mr Mike Szydlowski

Comments