Rip up the existing MBA and start afresh

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It is not difficult to find graduates and employers who will strongly defend the MBA’s reputation as the leading international business qualification.

Despite global recessions, growing competition and changes in business, the MBA has stood the test of time. Yet it is unlikely to retain its pre-eminent position without a fundamental review of its purpose and content.

Business schools deserve credit for adapting to change – subjects have been added to the MBA’s core curriculum, the list of electives has grown to offer more choice and practical modules focusing on leadership skills have been included.

But while attempts to respond to new business trends are to be applauded, the result is an MBA curriculum that is too crowded. A typical one-year, full-time MBA today requires students to complete about 10 core courses followed by up to seven electives. That is 17 assessed courses in nine months. In the US, where the two-year MBA prevails, the numbers double.

Such breadth and variety in the curriculum is great, but what about the depth? And where will it all end? Business trends will continue to emerge, as will arguments for including more subjects. But in trying to be all things to all people, business schools are not doing themselves justice. Meanwhile the MBA is losing its educational value.

What is needed is a review of the MBA and a more innovative approach to its design and delivery. A good start would be to rip up the existing model and start again, focusing on the MBA’s primary objective – to develop effective business people. Rebuilding the degree in this way would produce a very different MBA.

The redesign would allow scope for considering how to develop skills as well as knowledge, how to make better use of students’ existing experiences and how to incorporate innovative learning and assessment methods. There would be opportunities to develop a more integrated curriculum and to combine the benefits of e-learning with intensive face-to-face tuition or coaching.

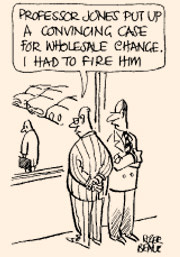

Business schools may resist radical change – especially those overly influenced by the rankings and accreditation agencies. They will be reluctant to do anything that might put their status and positioning at risk.

Then there are academic staff to consider, many of whom have an interest in maintaining the status quo and protecting their teaching and research interests. Top faculty staff are scarce and can wield a lot of influence internally. Against this backdrop, deans are understandably cautious about upsetting – and potentially losing – their best people.

These obstacles, whether real or perceived, might explain why the MBA has developed over the years without any serious re-engineering. Apart from internal considerations, business schools could also argue that there is no incentive to change. Although enrolment is declining at many schools, others continue to recruit high numbers of students. With no apparent let-up in demand, it would be tempting to assume the MBA is delivering what is required. So why change?

The answer comes in two parts. First, future demand for the MBA cannot be guaranteed. With the economic decline, fierce global competition for students, soaring costs of delivery (which push up tuition fees) and declining domestic student markets, many well-established business schools will struggle to survive.

Second, the MBA is not delivering on all fronts. It works because it has a longstanding international reputation; it attracts highly talented, ambitious people and it gives them opportunities to reflect, engage with others and expand their learning. This is all good stuff, but much of it happens regardless of what is taught.

The MBA is a valuable and respected qualification. But business schools, in responding to demands for yet more content, have lost sight of the MBA’s primary purpose. Now is the time for a fundamental review. An opportunity exists to create a dynamic MBA; one that not only continues to be relevant and important but also has real educational value.

Jeanette Purcell is a leadership development specialist and managing director of Jeanette Purcell Associates. She was chief executive of the Association of MBAs from 2003-2010.

Comments