China migration: At the turning point

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Deng Xiaoping left his rural village of Guang’an in 1919 to study in Paris, he was leaving behind a desperately poor agricultural community in Sichuan province where standards of living had barely risen in over 200 years.

Podcast

China’s shrinking Labour force

A shrinking labour force is driving huge economic change in China. James Kynge talks to Jamil Anderlini about the human cost of China’s mass migration from rural areas to the cities and why it is now beginning to slow.

Sixty years later, when Deng’s historic economic reforms unleashed a wave of migrants that powered the country’s transformation into an industrial powerhouse, his fellow villagers from Guang’an led the charge.

China’s farm output soared in the 1980s as agricultural communes were dismantled. By allowing farmers to keep a portion of what they produced, Deng gave them incentive to boost their yields. But Guang’an’s hilly landscape was unsuitable for mechanised agriculture, blunting the gains from reform.

“The land was bad. You could scrape at it the whole day but it was no use. People used to fight over a bit of fertiliser,” says Shen Xiaozhen, 77, recalling life in Guang’an after Deng’s reforms were introduced in 1978. “Outside you could earn more in a day than in a week back here. The money people sent back was important to our lives here.”

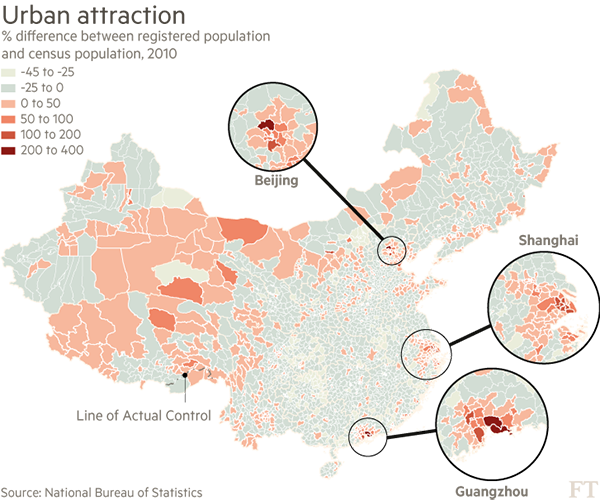

As a share of its population, Guang’an was the biggest contributor to China’s “migrant miracle”, three decades of breakneck economic growth underpinned by an unprecedented flow of labour from countryside to city, according to a Financial Times analysis of data from China’s 2010 census. Nearly a third of Guang’an’s 4.7m registered inhabitants no longer live here.

Now, however, economists say the most dynamic phase of China’s transformation to an urban society is complete. The once-limitless pool of impoverished rural labour from areas like Guang’an is rapidly drying up.

FT Series

End of the migrant miracle

‘Migrant miracle’ nears an end

The flow of rural labour that fuelled China’s economic boom is petering out

Policy bottlenecks add to labour shortage

Reform of the unloved hukou system proves difficult

Video: China at the Lewis Turning Point

The end of surplus labour has profound implications for the Chinese economy

China’s great migration

When China’s 170m rural migrant workers head home it is the biggest movement of people on earth

The end of surplus rural labour — a significant milestone that economists call the Lewis Turning Point — carries profound implications for China’s economy. As the flow of low-paid migrants into Chinese factories slows, workers demand higher pay, a phenomenon that has been evident for several years. This either drives low-end manufacturers out of business or forces them to raise prices, actions that could slow the export growth that has helped drive the country’s economy for decades.

“Labour and capital will become more limited and more expensive,” says Ha Jiming, investment strategist for private wealth management at Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong. “The economy will rebalance as exports slow due to rising factory prices. Investment will have to slow. That’s exactly what we’re seeing in real estate and manufacturing.”

Growth drivers

Many of the characteristics that have defined China’s economy over the past decade — fast growth, rising inequality, high savings and investment, big trade surpluses — can be traced in large part to the waves of migrants that flowed into China’s factories and construction sites from small towns and villages.

The National Bureau of Statistics estimates the number of people working outside their hometowns for at least six months was 278m last year. If they were a country, China’s migrant population would be the world’s fourth largest.

China’s growth in gross domestic product is forecast to slow to 6.1 per cent from 2016-2020, from 9.8 per cent in 1995-2009, according to estimates by Cai Fang, vice-president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, which advises the government. A shrinking labour force is the main factor.

Development economist Arthur Lewis laid out the turning point theory in 1954 to explain how wages stay low in agricultural economies that undergo rapid industrialisation. Since then, the idea has been commonly applied to the “Asian tigers” such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When industrialisation begins, Lewis explained, the reallocation of labour from farms, where productivity is low, to the urban industrial sector fuels rapid growth. But the fruits of this development flow disproportionately to business owners because the deep pool of excess rural labour ensures wages stay low.

This dynamic explains the extraordinarily high rates of savings and investment that are hallmarks of China’s economy. Knowing they can easily find fresh workers, factory owners and property developers boldly expand their operations. Rising profits fuel further investment, creating a positive feedback loop. Cheap labour and high savings produce trade surpluses, big foreign exchange reserves and a rising currency. Asset bubbles can also develop, as China has seen in its real estate market.

Eventually, however, the rural wages begin to converge with the industrial sector. At that point, labour shortages appear and urban employers must offer higher wages to lure workers from the countryside. Corporate profits, export competitiveness and asset prices fall.

“When I wrote an op-ed in 2004 called ‘A labour shortage in China,’ my friends laughed at me. Now it’s obvious to everyone,” says Huang Yiping, economics professor at Peking University’s National School of Development.

Today, few working-age people are visible on the streets of Guang’an’s rural towns and villages. Children and the elderly comprise the bulk of the remaining population.

Urbanisation

Cheng Dequan, 64, a retired primary school teacher, says that his village school, a two-hour walk up muddy hillsides from the town centre of Linshui county, is mostly deserted.

“The village school is still there, but there are only two grades and maybe 10 students. They can’t keep it going. The parents have all gone to work in cities,” he says. His village had 500 people before. Now there are only 30.

While many villagers from Guang’an went to far-off cities, Mr Cheng moved to a comfortable flat in a nearby “county town”. Home to just a few government buildings a decade ago, the town is now bustling. Though classified as a rural area, it is in reality already urbanised.

At an open-air restaurant in Linshui’s county town, the children of farmers dine on Chongqing-style hot pot, drinking beer and talking loudly. Thick steam pours out from tables of unfinished wood where pig brains, cow stomachs and duck kidneys boil in a spicy broth. The change to his home town is almost unimaginable for Mr Cheng, who recalls dinners of a single sweet potato shared among his wife and young children in the late 1970s.

County towns are key to understanding China’s changing demographics. Officially, 48 per cent of the country's 1.4bn people still live in the countryside, a figure suggesting plenty of room for further labour migration.

However, separate data that classifies employment by sector show only about 30 per cent of the population is engaged in agriculture. Mr Cai says that when various statistical distortions are corrected, the true share of agriculture in the labour force is a mere 20 per cent.

“If you go to the villages, I’m sure you won’t find any agricultural labourer under 30 years old. They’re just not there,” says Mr Cai.

Now, labour scarcity that began in export hubs like Guangdong province has arrived in Guang’an, where the supply of workers was once the most plentiful. That has caused difficulties for officials like Gan Zhiyong, mayor of Heliu town in Linshui county.

Three things we learnt from making a China migration choropleth

“People have the impression that salaries are higher outside, but that’s changing. Now our labour costs are very high,” Mr Gan says from a simple office with no computer and a bedroom in the back. Official data show migrant wages have risen from Rmb861 ($139) per month in 2005 to Rmb2,864 today.

Even if wages in rural towns remain lower than in the city, the gap is now close enough that some would-be migrants choose to stay closer to home for a better quality of life. “Fewer people are going out than before. People want to stay here and take care of their children,” Mr Gan says.

The dwindling flow of migrants is one aspect of China’s shrinking labour force. But the slowdown in urbanisation is coinciding with a rapid ageing of the population, another key shift underlying the Lewis Turning Point.

China’s one-child policy created a “demographic dividend” for the economy between roughly 1980 and 2014. Now that dividend is turning into a deficit. The population of Chinese aged between 15 and 64 peaked in 2013, Mr Cai notes. The ratio of children and elderly to working-age Chinese — the dependency ratio — began rising in 2011. The one-child policy was introduced in 1979, but the birth rate kept rising into the 1980s. Annual births in China hit 25m in 1987 and have steadily dropped ever since, hitting about 20m a year by 1997 and falling to 16m last year.

“Starting in two or three years, you’re going to see another substantial, precipitous drop in young labour entering the labour market,” says Wang Feng, an expert on Chinese demographics at the University of California Irvine and Fudan University in Shanghai.

Rebalancing act

Yet reaching the Lewis Turning Point has a bright side. For years economists have warned that the outsized share of savings and investment in China has led to distortions within the country and lopsided trade relations with the world.

This high investment has led to wasteful construction, capital misallocation and excess capacity. Unused highways and “ghost cities” of empty apartment buildings are a common feature of China's landscape. A bloated industrial sector where steel mills, shipyards and solar panel factories produce more than the country can use have led to tensions with trading partners, which complain of China “dumping” excess output.

Lewis’ theory explains how changes in labour dynamics can help correct these problems, promoting the kind of economic rebalancing that government policy has so far failed to achieve.

Rising wages gradually eat into profits and investment, so “rebalancing happens naturally”, says Ross Garnaut, economist at Australian National University and co-editor, with Mr Huang, of a collection of papers on China at the Lewis Turning Point. “The turning point forces rebalancing to happen.”

Any rebalancing will fundamentally reshape China’s economy and its trade relations with the rest of the world. In the pre-turning point era, real estate, infrastructure and smokestack industries dominated the economy. In the new era, service industries like healthcare, media, financial services and tourism will thrive. And instead of imports tilted towards commodities like crude oil and iron ore, China will buy more food and other consumer goods.

The changes Deng’s reforms set in motion in Guang’an and across China were possible because of a set of circumstances that are rapidly disappearing. For China to keep moving towards a place among the ranks of rich countries, it needs to grow by improving urban productivity, rather than simply by moving people off the farm to work in low-end industrial jobs.

“There is no need to fear the slowdown of the potential growth rate,” Mr Cai says. “The new stage of development, however, requires China to accomplish a fundamental transformation of its economic growth pattern, from sole reliance on inputs of capital and labour to greater improvements in total factor productivity.”

Comments