US economic recovery masks tale of many cities

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

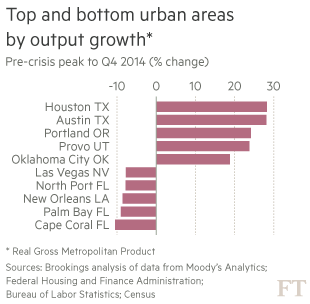

Nearly half of the biggest US metropolitan areas have yet to recoup all the lost jobs from the Great Recession and almost a third have failed to return to previous levels of output, according to analysis that underscores the fragmenting urban fortunes beneath the surface of America’s recovery.

Research on 100 urban areas from the Brookings think-tank, reveals an economic patchwork in which the legacy of boom and bust hangs heavily over cities in Florida and inland California, while at the other end of the spectrum, technology and bioscience-focused cities such as Austin, Texas, San Francisco, and Raleigh, North Carolina have comfortably surpassed their previous peaks.

“This may be the norm now — extreme variation,” said Mark Muro, policy director for the Metropolitan Policy Program at Washington-based Brookings.

Economic activity across the US is nearly 10 per cent above its pre-recession peak and employment is 3.8m higher. Yet on a visit to Rhode Island last Friday, Janet Yellen, the Fed chair, said that even six years after the recession ended the US labour market has yet to fully recover and that the outlook was only for “moderate” growth.

Regional ups and downs are nothing new in the US. However, if the nation remains stuck in its current slow-growth rut, it will leave the weaker city economies particularly vulnerable, said Ross DeVol, chief research officer at the Milken Institute, a California think-tank.

Adding to the faultlines are socially combustible divides running within urban areas such as Chicago and Baltimore, which was the scene of recent riots. “There are a lot of factors pulling things apart,” Mr DeVol said.

The Great Recession was initially most devastating in real estate and financially focused parts of the US, whereas areas with large government, higher education or health sectors were better insulated. Among the top performers today are those with the sharpest focus on digital technology and advanced manufacturing, while cities that cashed in on the oil boom are showing early signs of being buffeted by falling investment.

The big US city with the fastest-growing population last year was Austin. Cotter Cunningham, who runs online vouchers company RetailMeNot, watched his house in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, lose half its value during the crash before being lured to the Texas capital. “Here it feels like there was much less of a depression,” he said.

Employment in the Austin urban area is 16 per cent above its pre-crisis peak and real output is 28 per cent higher, according to Brookings. The state capital is riding the tech boom in part because of a strong university system, cheaper land and a lifestyle that is attracting young, well-educated workers to a state with no personal income tax. Its diversified economy may help it withstand the worst of an oil industry slump that risks pushing Texas as a whole into recession.

Mike Wilson, operations vice-president for online legal services company LegalZoom who quit his native Los Angeles in 2009, describes trendy Austin as a “truly shiny place”.

In Florida, a boom state a decade ago, shine remains absent in many cities because of the persistent drag from the housing crash.

The Palm Bay-Melbourne-Titusville area, which was at the centre of a speculative boom before America’s property crash, has house prices that were 48 per cent below their peaks at the end of last year, according to a Brookings analysis based on Federal Housing Finance Agency data, which include home refinancings. Employment and output were both more than 9 per cent lower. Median household incomes were $46,472, far below Austin’s $61,750.

Ms Yellen argued last week that the housing blight was set to fade, pointing out that the share of mortgages that are underwater has fallen by a half nationally between 2011 and 2014. Victoria Northrup, president of the Greater Palm Bay Chamber of Commerce, argues there are positive signs among businesses in her area, with construction of retirement homes surging again as baby boomers prepare to retire.

However the message from analysts is that cities need to diversify their economies broadly — as places like Austin have done — if they are to weather future slumps.

That said, even cities that are successfully harnessing the IT and advanced industry wave are struggling to extend the benefits widely among their populations. San Francisco, for instance, has the second highest income inequality of 50 major cities as the fortunes of its ultra-educated tech aristocracy ride high, and resentment over rising housing costs is acute.

On the east coast that divide is glaringly apparent in Baltimore. While the immediate cause of the recent riots that received global attention was the death of a black man in police custody, residents said the violence was just the symptom of an economic cancer that has emerged over previous decades.

As manufacturing jobs disappeared with the closure of the steel mills that once formed the city’s economic bedrock, poor neighbourhoods have seen drug-related crime emerge as the economic engine.

Money has poured into the pepped-up business and tourist district near the harbour, but in the poorer areas of the city, which are populated mainly by African Americans, a complete lack of investment means the unemployment rate for men is estimated to be 50 per cent.

“Depending on what zip code you live in, your life expectancy can be as different as 30 years,” said Ben Cardin, a Maryland senator.

Mr Muro said: “There can be tremendous deprivation in urban neighbourhoods that are quite adjacent to booming new innovation districts.”

In Chicago, community leaders talk of there being two cities — the resurgent downtown with its corporate headquarters, tech hub and new MATTER medical technology start-up centre — and the poor southern and western reaches of the city.

Until cities like Chicago and Baltimore succeed in equipping poorer citizens with the skills and education they need to tap into growth industries, such divides will remain raw and socially dangerous.

Ricardo Estrada, who helps run Instituto del Progreso Latino, a Chicago charity supporting Latino immigrants, puts it succinctly: “Downtown is a different world.”

Comments