Hollywood transformed

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

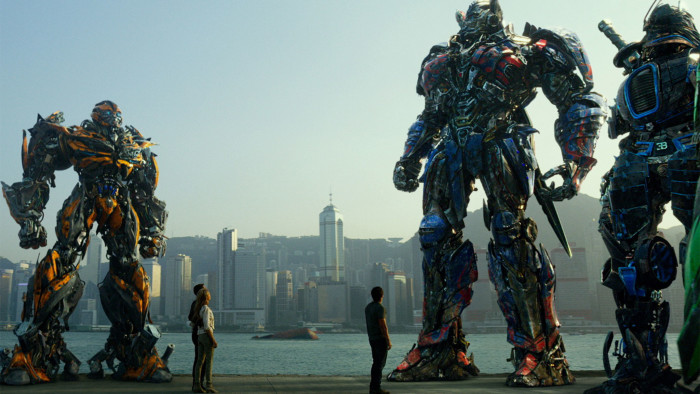

Nobody said global takeover would be easy. On course to beating Avatar (2009) as the top-grossing film of all time at the Chinese box office, Transformers: Age of Extinction picked up a flurry of complaints from Chinese companies who had paid for their products to appear in the movie.

A Chinese takeaway chain that sells duck necks said it was “very dissatisfied” with a three-second shot of its meat in a refrigerator; the Wulong Karst National Park was upset the US production team had mistaken a sign that read “Green Dragon Bridge” for the park’s actual logo, and given the impression the park was near Hong Kong, when they are actually more than 700 miles apart. Clearly, the park owners had never seen Michael Bay’s movies, with their cheerful war on all manner of coherence: spatial, geographical, narratological.

“Why do all the cars that fought in Hong Kong have their [steering] wheels on the left?” one movie-goer asked on Weibo, the Chinese Twitter, where many gathered to puzzle over the movie’s numerous product placements. “Why would a middle-aged man in the middle of the desert in Texas take out a China Construction Bank card to withdraw money from the ATM?” asked another.

A fitting image, perhaps, for the new breed of eastward-bound Hollywood blockbuster, aimed at penetrating China’s “Great Wall” quota system – limiting the number of foreign films shown and the profits passed on to its makers – by gaining coveted “co-production” status.

Working with their Chinese counterparts, Jiaflix Enterprises and the China Movie Channel, the producers of the fourth Transformers film shot the movie partly in China. They also cast Chinese stars Li Bingbing and Han Geng in small roles, and made multiple product-placement deals with Chinese consumer brands, although by far the strangest endorsement in the film has to be for single-party, non-democratic rule. While western democracy is represented by a Cheney-esque goon heading up the CIA and running rings around an ineffectual president, the response of the Chinese government to alien invasion is one of efficient, disciplined resolve. “Transformers: Age of Extinction is a very patriotic film,” noted Variety, “It’s just Chinese patriotism on the screen, not American.”

…

The last time America found itself in rivalry with a communist bloc, the Soviet Union, the result from Hollywood was a ruthless demonisation of war-hungry reds, in everything from Red Dawn (1984) to Rocky V (1990). But Russia was not then, as China is now, home to the largest film studio in the world and the fastest-growing film market. Last year it eclipsed Japan to become the number two film market in the world. This year, box office rose 33 per cent in the first quarter to $1.13bn, swelled in large part by Transformers, which so far has taken $306m in China alone, far more than the film’s North American gross of $227m – an “almost unheard of” ratio, according to Variety. In a year that has seen the American box office go into freefall, down nearly 20 per cent on last year’s, China’s has continued to soar, and is expected to reach $4.8bn by the end of the year. In 2020, the Chinese market is expected to eclipse North America’s altogether.

“What’s driving the growth is they’re building cinemas at an astonishing rate,” says Rob Cain, a film producer who specialises in China-US co-productions. He predicts that at their current rate – anywhere between 10 and 13 new cinemas a day – China will have 60,000 screens in 10 to 15 years. “The centre of gravity is shifting so rapidly to China and Asia – not just the market but also the money and capital for American movies – that their opinions are going to matter much more. Ultimately, China is going to be not just the biggest market but also the arbiter of what can get made and will get made.”

Those worried about Hollywood’s possible evolution into China’s entertainer-in-chief have missed the boat – it has already evolved into that role. It’s hard to miss the Asiatic tint to the past few summers at the multiplex – everywhere you look, films are setting down in Beijing and Macau, sprouting cameos by Chinese stars, and product placements for goods western audiences have never heard of. The producers of World War Z (2013) removed a discussion over whether the zombie apocalypse started in China; Chinese villains were edited out of Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007) and Men in Black 3 (2012). When the writers of Battleship (2012) turned in a draft in which aliens only threatened the US, the premise was deemed “too American”. These days, movie monsters head straight for the West Coast, laying waste to San Francisco and the Philippines, the better to sweep the entire Pacific Rim, threatening Hawaii and Hong Kong, as did both Godzilla in this year’s big budget remake and the alien gigantosaurs of Pacific Rim (2013) – another ready-made symbol for the invading Hollywood behemoth, perhaps.

…

“Ten years ago China was an afterthought as a market,” says Bruce Nash, a box office analyst. He points to the $100m earned at the Chinese box office by James Cameron’s Avatar and the 2012 decision by Chinese leaders to allow 34 movies a year to be shown in China (up from 20, on the condition the additional 14 be shown in 3D or in jumbo-sized Imax format), as the key moments in the country’s evolution as a film market. “Being able to hit $100m in one territory is huge. In order to be the biggest movie of the summer you now have to spend $400m. In order to make that back, you’ve got to be making as much in China as you do in the US, so somebody has to figure out how to appeal to both of those markets, without offending either of them.”

There have been notable missteps. Last year, the producers of Iron Man 3 aimed for coveted co-production status but ended up cutting two different versions of the film. In one, a doctor in China named Dr Wu (played by Chinese movie star Wang Xueqi) sees Iron Man challenge the Mandarin on TV and says (in Chinese): “[He] doesn’t have to do this alone – China can help,” before pouring himself a glass of Yili brand Chinese milk; later, when Tony Stark decides he doesn’t want to be Iron Man any more, he goes to China for the operation – scenes absent from the US version. “No one comes to China for medical care,” quipped Beijing-based blogger Eric Jou in a post entitled “Why many in China hate Iron Man 3’s Chinese version”.

At the same time, the film’s backpedalling on the ethnicity of the Mandarin – in the comic books, an inscrutable Fu Manchu-style villain; in the film a cockney actor played by Ben Kingsley, who is duped into the role – angered many American comic book fans. “[The director Shane] Black (and Marvel) . . . sufficiently wiped their ass with decades of Iron Man history, reducing Shell Head’s lone significant adversary to a punchline,” griped one online commentator. An interesting conundrum: many comic books properties draw sustenance from xenophobic stereotype – the yellow peril, the evil hun, and so on. Soften them, in the interest of the global market, and you dilute what gave the property a kick in the first place.

While Iron Man 3 took $121m in China, its bifurcation into two movies suggests limits to Hollywood’s global ambitions. Transformers: Age of Extinction was essentially two movies, too, the first half set in North America and climaxing with a robot-on-robot fight in Chicago; the second half set in China, climaxing with another, even bigger fight in the streets of Hong Kong. As Hollywood strains to be all things to all markets, it is testing the limits of coherence and audience affiliation. “As Hollywood gets deeper into this changing relationship, they’ll get better at it,” says Phil Contrino, chief analyst at the database BoxOffice.com. “I even think from Iron Man 3 to Transformers there’s been an improvement. This is the infancy of the potential that this market has. So we’re taking baby steps and eventually we’re going to walk. For Transformers’ Chinese grosses to be blowing away the North American grosses like that is a groundbreaking moment in the dynamic between the two film cultures.”

These are, indeed, interesting times for Hollywood, which by combined accident of geography, history, and national temperament, has long enjoyed its status as unchallenged cinematic hegemon but now finds itself in the role of global jukebox, with other countries piling in the quarters.

In some ways today’s traffic in global juggernauts bears a resemblance to the silent era, when the national cinemas of Europe and America competed with historical epics – Intolerance (1916) was DW Griffith’s conscious attempt to outdo the 1914 Italian epic Cabiria for spectacle.

With the arrival of sound, and the erection of language barriers around the national cinemas of every country except the one poised to take most advantage of its English language heritage, America began its slow, steady ascent to pole position. In 1950, Stagecoach producer Walter Wanger called Hollywood a “celluloid Athens”, transmitting American values to a world not even aware it was soaking them up.

It was Steven Spielberg’s dinosaurs that tipped the balance. In 1993, Jurassic Park helped push Hollywood’s overseas revenues ahead of its domestic revenues for the first time, and the figure continued to inch forward every year: it now sits at an astonishing 70 per cent. Periodically, the American public wonders why popular US comedies such as Zoolander do not merit sequels but “flops” like Battleship and Pacific Rim do but, overseas, those films were not flops at all. The American audience’s power has never counted for less.

“The overseas market has changed the DNA of American movies,” says film historian Neal Gabler. “The bigger-faster-louder aesthetic is very deeply embedded in the Americans psyche. No one else can do it. It’s one of the reason they export so well. It’s so much a part of who we are. But we have been victims of our own success. It’s a Catch-22. The things that make our movies so popular overseas are now larger than the American market can support by itself. The giganticism must be subsidised.”

Whether China can eclipse Hollywood in the production, rather than just consumption, of blockbusters is a question that leaves industry watchers curious. One of the results of the flood of American movies into Europe after the second world war was the French new wave, during which a generation of French film-makers filtered back to Hollywood their own heavily accented, free-form takes on the detective flicks and pulp fiction they had soaked up in their youth. Might there not come a day when US teenagers don 3D glasses to watch Jet Li save the world from aliens in a Chinese-produced blockbuster?

“Maybe not in the same numbers that go to see a US-made film,” says Bruce Nash, “but there will be a cycle of that. Chinese film-makers will invent new ways of telling stories and that will get cross-fertilised in Hollywood.” A Chinese superhero movie based on the terracotta army sculptures is moving closer to fruition with the help of Paramount, while the 2012 Chinese-made hit Lost in Thailand “feels very much like The Hangover,” says Phil Contrino. “They’re learning. They’re upping their production standards. The more money they put into these movies, the more they learn about storytelling techniques, the better they’re going to get. It’s happened quicker than Hollywood would have expected it to.” Or liked.

Tom Shone’s ‘Scorsese: A Retrospective’ will be published by Thames & Hudson in October

——————————————-

View from China: ‘The milk box just puts viewers over the edge’

About two hours into Transformers: Age of Extinction, theatres in China begin to ripple with the nervous laughter of unintended comedy, writes Charles Clover. As the action in the movie shifts from Texas and Chicago to Beijing and Hong Kong, the Chinese product placements start flying faster than bullets from an Autobot’s wrist-mounted Gatling gun.

The tipping point is a scene in which actor Stanley Tucci, who plays a billionaire inventor pursued by CIA assassins, flees to the top of a Hong Kong high rise. On the roof, for some inexplicable reason, he finds a refrigerator. And in that fridge is a carton of Yili Shuhua, a Chinese brand of milk that Tucci delightedly sips for a full six seconds of airtime.

By this point, Chinese viewers have already been bombarded with everything from Chinese Red Bull to Lenovo to Zhou Hei smoked duck meat but, for whatever reason, “the milk box just puts viewers over the edge”, says Jiang Xiaoyu, movie critic for CCTV and chairman of Chinese Film Promotion Society. Jiang calls the movie an example of a new Hollywood genre: “special delivery to China”.

“These movies are taking advantage of the Chinese consumers, who have a big ego trip when they see something Chinese in a Hollywood movie. They’re like the chairman of a company who is thrilled to see his logo on top of a building,” he says.

The fourth instalment of the Transformers series is the most audacious example of this trend to date, and by far the most commercially successful. “They have made the right business model, even if it’s not the right movie,” concedes Jiang. Indeed, viewers have forgiven the ham-fisted shopping channel-like advertising; in the 26 days it has been shown in China to July 22, the film has already made an astonishing $306m in China, according to Entgroup, the Chinese film and entertainment research firm.

China Construction Bank, Nutrilite vitamins, C’est bon water, LeTV’s online streaming set-top box – all appear in a surreal and slightly arbitrary way amid the film’s intergalactic robot war. However, some Chinese companies are fuming that they got short-changed on airtime after spending small fortunes to be in the film. Beijing’s Pangu Hotel settled with Paramount Pictures after it launched a suit claiming it was not given enough air-time.

Hollywood’s fascination with China is only just beginning. In the past year and a half since the end of 2012, the number of movie screens in China increased by more than the total number of screens in France, growing from 13,185 to 22,000, according to a report of the China Film Industry. Crucially, for the moment Chinese audiences are not too choosy. “The film market in China is like an experimental supermarket – with more and more racks but only one product” says Zhang Xiaobei, founder of a review programme on CCTV. “The viewers don’t care what they see as long as it’s a film. They’ll watch whatever is put in front of them.”

Charles Clover is the FT’s Beijing correspondent

Photographs: Industrial Light & Magic/Paramount, ChinaFotoPress

Comments